Concern for Patient Decompensation

Rapid Response Teams (RRT) were invented as a way to achieve emergent evaluation and treatment of decompensating hospitalized patients to prevent cardiac arrest. They are effective and associated with decreasing incidence of unexpected cardiac arrest in the hospital. When a nurse identifies that a patient may be developing a new or life-threatening condition, they can activate this response system that will lead to a mobilization of resources and rapid bedside assessment.

Common reasons nurses call an RRT are vital sign changes, chest pain, hypotension, and shortness of breath. Sometimes RRTs are activated for trivial reasons, but ultimately, the system saves lives and every RRT should be taken seriously. Our job is to rapidly figure out what the underlying issue is that triggered the change in the patient’s clinical status.

I was drawn to hospital medicine by the allure of walking from room to room, warm coffee in my hand, carefully interpreting tests, and focusing on good patient communication while I advanced care over hours to days. As a medical student and junior resident, I found hustling into a room, making a new diagnosis, and/or changing the care plan within seconds to minutes to be difficult and terrifying. Below is a framework to help you approach some common situations.

Possible RRT Situations

The differential diagnosis for chest pain is broad and often requires a careful history, physical exam, and chart review. In the heat of the moment, first make sure the patient does not have a life-threatening cause for the chest pain. The conditions to pay most attention to are ACS (acute coronary syndrome), PE (pulmonary embolism), pneumothorax, and aortic dissection. Don’t miss these conditions. A standard evaluation includes an EKG Look at the EKG ASAP . . . make sure this isn’t a STEMI, troponin (depending on the situation, if the initial result was negative, repeat troponin 3 to 4 hours after the initial result), and physical exam (pay attention to heart and lung sounds and check for leg swelling). If there are new or worsening respiratory complaints, my threshold to obtain a chest XR is low. If the story is suspicious for aortic dissection, this can be evaluated further with CT imaging. PE can be investigated by CT imaging or VQ scan.

The first step is to make sure the patient is oxygenating adequately. This may require an escalation of oxygen therapy to a non-rebreather while you try to figure out what is going on. If you can’t get the oxygen level to 88% or higher with a non-rebreather and the patient is in respiratory distress, they likely need emergent positive pressure ventilation, CPAP or BiPAP, or to be emergently intubated (if that is within their goals of care). If this is the case, ask for help early from your favorite hospitalist with intubation privileges, intensivist, ED provider, or anesthesiologist.

Another emergent situation that may arise is an unresponsive or minimally responsive patient who is breathing very slowly. If they have been getting opiates, give a dose of naloxone (Narcan), 0.4mg (standard dose). When in doubt, try naloxone. It works in seconds, and the downside is low. If that doesn’t work, consider checking a blood gas to see if they have a respiratory acidosis, which indicates hypoventilation with CO2 narcosis versus proceeding to emergent intubation (depending on the situation).

If the patient is not protecting their airway, audibly choking on their secretions etc., start with suctioning as your first intervention. Then, if necessary, move to emergent intubation. Don’t forget to consider anaphylaxis. If a patient is struggling to breathe, wheezing, or has recently started a new medication and has other signs of anaphylaxis, such as a new rash or hypotension, get them a dose of intramuscular epinephrine as soon as possible.

One final emergency you may encounter is a tracheostomy tube that has fallen out. Details of how to manage this are beyond the scope of this rotation, but if the trach is “fresh” (has been placed in the last couple days), DO NOT try to replace it. It may end up in the soft tissues of the neck, which can be a disaster. Involve your ENT consultant and get the patient intubated in the normal fashion while you wait for the ENT to show up. If the trach is old, the tube can be reinserted.

Once you have stabilized the oxygenation and made sure the airway is secured, start your evaluation to figure out what is causing the respiratory issue.

A basic workup often begins with a CXR, EKG, physical exam, and brief chart biopsy. My threshold to check a blood gas is low, especially if the patient is ill appearing, usually venous (as opposed to arterial) blood gas is sufficient (as long as the pulse ox appears to be giving a reliable reading). This will tell you the pH and CO2 level.

First, confirm that the hypotension is “real.” Recheck the BP at a new site, the other arm for example, talk to the patient, and check the BP trend. Some patients, (for example those with severe chronic systolic heart failure or advanced cirrhosis), may have a systolic blood pressure in the 80s. If the hypotension is new and confirmed on recheck or the patient has newly altered mental status (can be from cerebral hypoperfusion), it is more likely to be “real.”

If the hypotension is real, categorize it as “shock”. Unless the patient is in obvious cardiogenic shock, start a bolus of lactated ringers or normal saline to see if it helps. Our next job is to figure out what kind of shock it is likely to be using physical exam and a chart biopsy. The broad categories are hypovolemic, cardiogenic, septic, obstructive, anaphylactic, or neurogenic, and further work-up and management will depend on the physical exam and patient history. Point of care ultrasound can also be very helpful to rapidly rule out cardiac tamponade and pneumothorax. If the mean arterial pressure cannot be maintained at 60 or above with crystalloid fluid boluses the initial pressor of choice is norepinephrine until we figure out what is going on.

Start by checking the glucose level, as hypoglycemia is common, life threatening, easy to diagnose, and easy to treat. See Altered Mental Status.

Code Blue: Cardiac Arrest

This section is written as if you are running the code. In reality, you may be standing next to me or rotating in to do chest compressions. Either way, get in the habit of imagining what you would do if you were in charge of the room—one day soon, you will be.

Sometimes things don’t go well and a hospitalized patient ends up in cardiac arrest. As you enter the room, it is packed full of people and stress. Now what?

-

Stay Calm

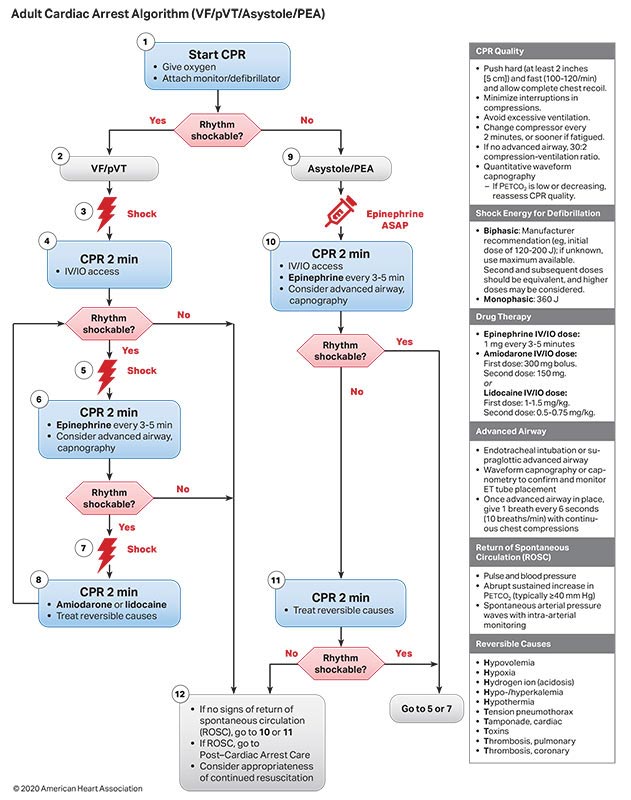

Check your pulse. Take a deep breath. The patient is already dead. How much worse can things get? You are going to do your best and already have an easy-to-follow algorithm from the American Heart Association telling you what to do (see below).

-

Chest Compressions

Someone should already be doing chest compressions. If nobody is doing them, ask a specific person to start. As the medical student, start doing them yourself or line up for a round of chest compressions.

-

Defibrillator

Someone should have the defibrillator turned on and pads on the patient's chest. If this hasn't happened, ask a specific person to do it.

-

Roles Filled

Make sure all the necessary roles are filled. Actually, this is the hardest part of the code. Identify the timer, recorder, pharmacist, pulse checker, nurse who is in charge of giving medications, next in line for chest compressions, and nurse or respiratory therapist in charge of bagging and airway management. Anyone who doesn't have a role should be kicked out of the room.

-

Pause

Pause compressions for your initial pulse and rhythm check. Have someone new rotate in for chest compressions.

-

Follow the Cardiac Arrest Algorithm

-

Ask a Nurse

Ask a nurse to give you a one-liner on the patient and read key lab data, recent potassium, hemoglobin, bicarb, pH, etc.

-

Ultrasound for PEA Arrest

If it is PEA (pulseless electrical activity) arrest get the ultrasound in the room early. If possible, have another physician do a quick point-of-care ultrasound exam to look for pneumothorax and pericardial effusion once ROSC is achieved or during a pulse check.

Image credit: Keeping Away Death, by Julian Hoke Harris, a sculpture on the former Fulton County, Georgia, Department of Health and Wellness building.