Modules

previous

Planetary Health

Next

Introduction to Climate Change and Mental Health

Material below this text is from the old page. Keep or delete any of it?

Mental Health in a Changing Climate

Mini Lesson: Mental Health and the Environment

In this mini lesson, you'll find:

- Case studies.

- Definitions.

- Review questions.

These materials are based on the PowerPoint presentation by Dr. Katie Hayes, , PhD, Senior Policy Analyst, Health Canada, Climate Change and Innovation Bureau

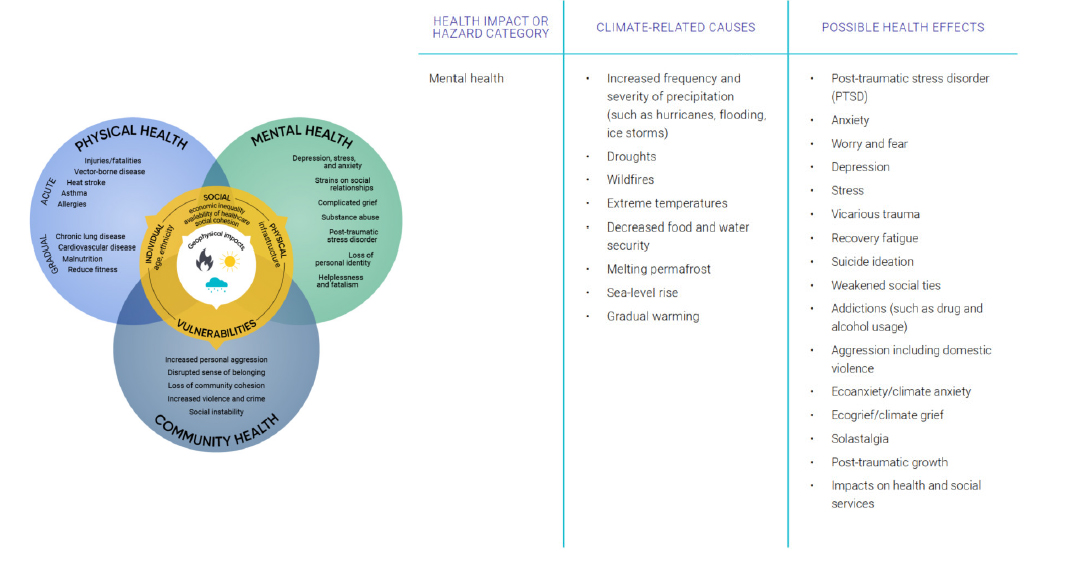

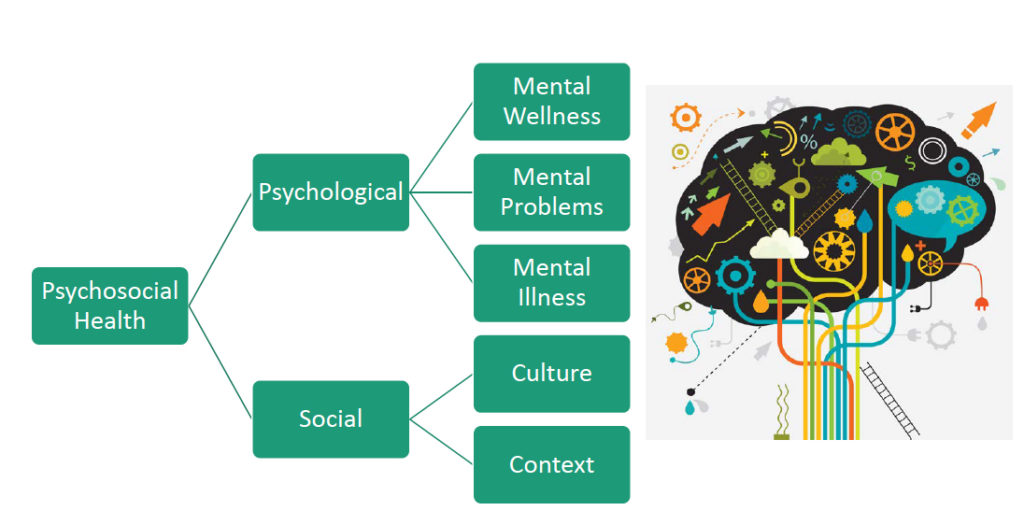

Climate Change Affects Psychological and Social Health

An Overview of Current Evidence

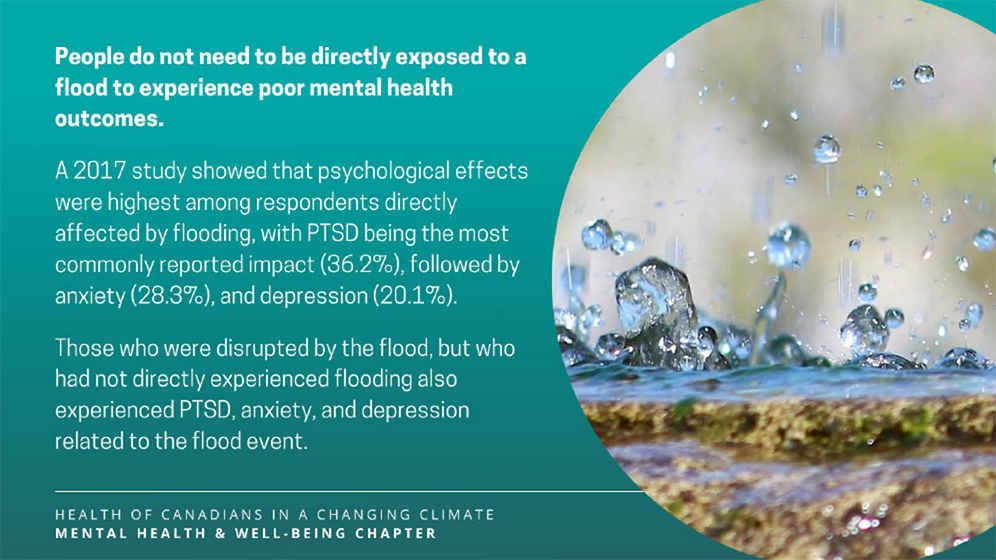

Key findings in the Mental Health and Well-Being Chapter from the report Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action.

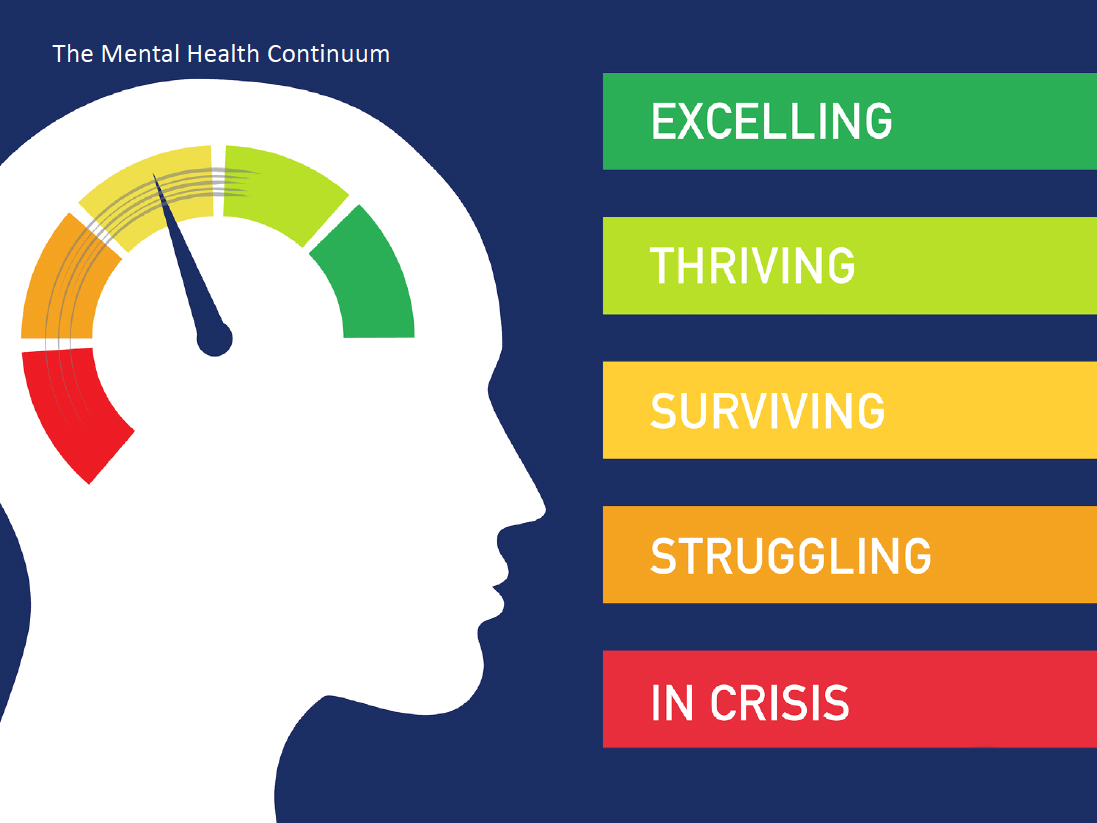

Mental health impacts of climate change may include:

- Exacerbation of existing mental illness such as psychosis.

- New-onset mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Mental health stressors such as grief, worry, anxiety, and vicarious trauma.

- A lost sense of place, which refers to the perceived or actual detachment from community, environment, or homeland.

- Disruptions to psychosocial well-being and resilience.

- Disruptions to a sense of meaning in a person’s life.

- General distress.

- Higher rates of hospital admissions.

- Increased suicide ideation or suicide.

- Increased negative behaviors such as substance misuse, violence, and aggression.

Sources: (image) Clayton, S., Manning, C. M., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M. (2017). Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica.

Hayes, K., Cunsolo, A., Augustinavicius, J., Stranberg, R., Clayton, S., Malik, M., Donaldson, S., Richards, G., Bedard, A., Archer, L., Munro, T., & Hilario, C. (2022). Mental Health and Well-being. In P. Berry & R. Schnitter (Eds.), Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada

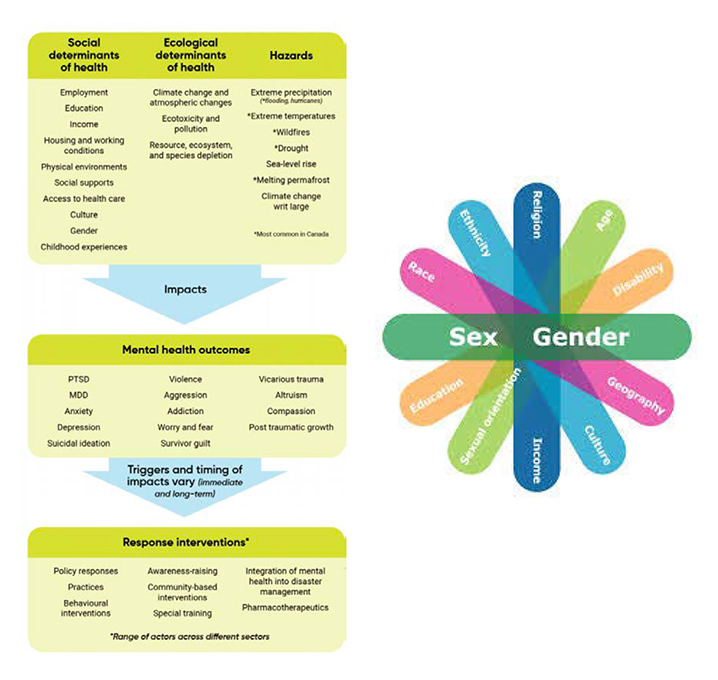

Health Equity

Explore the inequitable burden of climate-related mental health disorders and the determinants of health and intersectionality.

Populations at Greatest Risk for Mental Health Effects

Climate change disproportionately affects the mental health of specific populations, including:

- Indigenous peoples.

- Women. According to Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate, evidence suggests that women tend toward anxiety, worry, and PTSD related to a changing climate. In particlar, women tend to be in caregiving roles, which are typically undervalued and underpaid. In these roles, women are at greater risk of experiencing compassion fatigue, particularly during periods of exposure to climate hazards.

- Children and youth.

- Older adults.

- People living in low socio-economic conditions, including the homeless.

- People living with pre-existing physical and mental health conditions.

- Certain occupational groups such as land-based workers (e.g., farmers, farm workers, conservationists, foresters, etc.) and first responders.

Surveillance and Monitoring

- Gender (Female).

- Sex (Female, particularly pregnant women).

- Age (children, infants, older adults).

- Indigenous and Métis.

- Race and ethnicity (non-Caucasian, non-white).

- Immigrants.

- People with pre-existing health conditions.

- People with low-socioeconomic status.

- The under- and non-insured (health care and home insurance).

- The under-housed and homeless.

- Outdoor laborers.

- First responders.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Depression (including major depressive disorders).

- Anxiety.

- Suicidal ideation.

- Aggression.

- Substance misuse.

- Violence.

- Survivor guilt.

- Vicarious trauma.

- Altruism.

- Compassion.

- Post-traumatic growth.

- Other.

Key Considerations and Challenges to Data Collection

Attribution

Attribute environmental hazards to climate change, and then attribute mental health outcomes to these hazards.

Isolate Outcomes

Isolate the mental health outcomes related to climate change from other compounding life stressors.

Measure Impacts

Measure some types of mental health impacts and compounding stressors (e.g., the difficulty of measuring compounding stressors of those experiencing colonialism, intergenerational trauma, and connections to the land such as many Indigenous Peoples).

Study and Report Findings

Study and report on mental health indicators when mental health can be understood differently among diverse populations.

Watch for Under- or Over-reporting of Outcomes

Climate change outcomes on mental health are complex and nuanced due to timing, exposure, and may be under- or over-reported because the psychopathological patterns are similar to other disorders.

Climate Displacement

Climate-related environmental changes could lead to distress related to displacement.

Displacement related to climate change could reach 25 million to 1 billion by 2050. However, 200 million is the most frequently cited projection.

International Organization for Migrations reports displacement from environmental disasters more common now than displacement from violence and conflict.

- Distress related to loss of culture.

- Financial hardship.

- Family conflict.

- Impacts to future generations.

Experiences of racism, discrimination could be exacerbated by displacement due to climate change.

Trapped populations are less able to migrate due to social, political, or economic conditions.

There could also be positive psychosocial outcomes if displacement is voluntary, consented, last resort, planned, and improves ones standard of living.

Displacement due to severe weather events can cause long-lasting mental health impacts.

The related psychological and social effect to Indigenous communities may include:

- Increased emotional trauma.

- Homelessness.

- Substance misuse.

- Disrupted cultural practices.

- Discrimination.

The 2011 Manitoba flood displaced residents of Lake St. Martin First Nation for more than six years (approximately 7% of the evacuees never returned home, reportedly many cases were due to homelessness and suicide).

Mini Lesson: Climate Migration and Displacement

In this mini lesson, you'll find:

- Case studies.

- Definitions.

- Review questions.

Common Reactions to the Climate Crisis

New Terminology

The American Psychology Association (APA) describes eco-anxiety as “the chronic fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the seemingly irrevocable impact of climate change and the associated concern for one’s future and that of next generations.”

Eco-grief is mourning the loss of ecosystems, landscapes, species, and ways of life due to climate change.

Some people are more affected than others. Dr. Panu Pihkala, PhD, adjunct professor of environmental theology at the University of Helsinki said, “Many Indigenous peoples experience much more ecological grief because of physical, cultural, and social losses, which arise from a changing environment.”

Source: everydayhealth.com

Eco-paralysis refers to the inability to take effective action because the emotional distress is so great that certain psychological defense mechanisms (e.g. denial) become activated.

Source: URMC Rochester

Eco-guilt arises when people think about times they did not meet personal or societal standards of behavior to save the environment.

Source: Mallett, R. K. (2012). Eco-guilt motivates eco-friendly behavior. Ecopsychology, 4(3), 223–231.

Solastalgia (a combination of solace and nostalgia) is a term to describe feelings of sorrow and loss associated with the destruction of one’s home environment or cherished landscapes.

Source: Albrecht G, Sartore GM, Connor L, Higginbotham N, Freeman S, Kelly B, Stain H, Tonna A, Pollard G. Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15 Suppl 1:S95-8. doi: 10.1080/10398560701701288. PMID: 18027145.

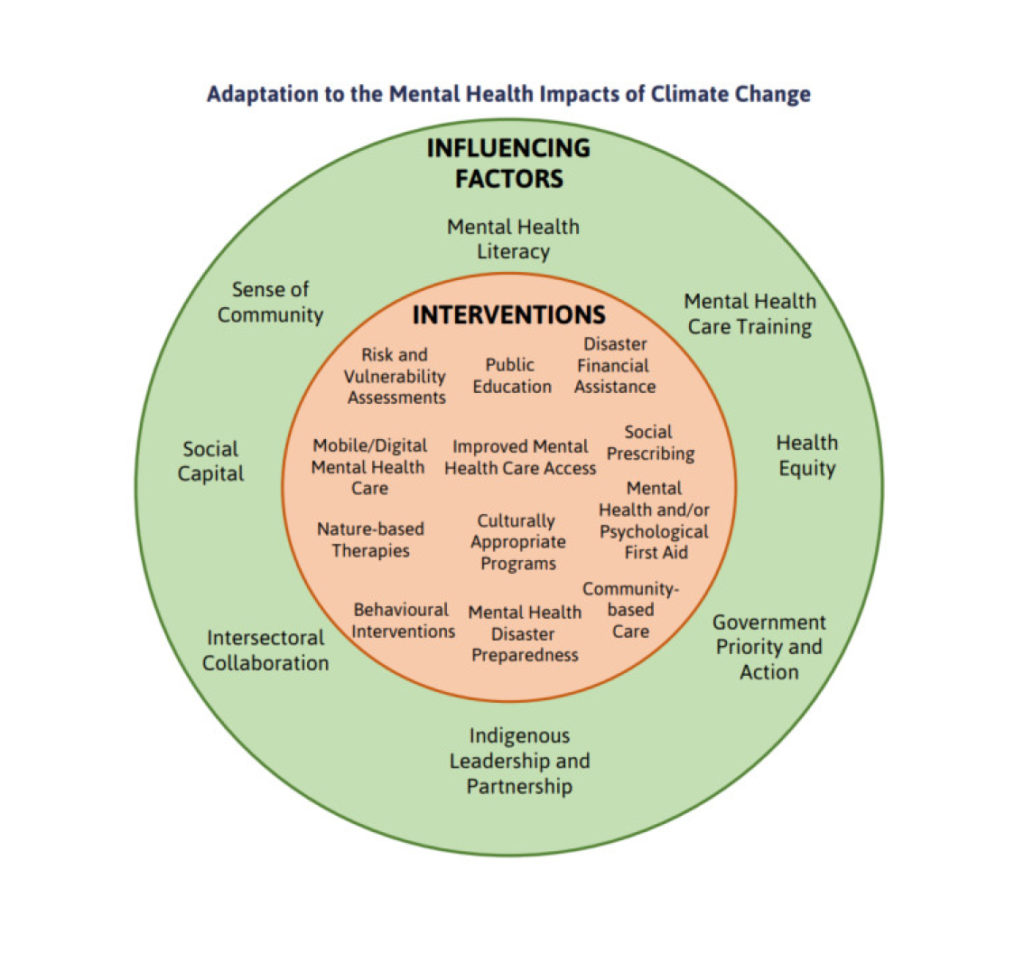

Cope and Adapt

Factors That Influence Adaptation

Source: Hayes, K., Berry, P., & Ebi, K. L. (2019). Factors Influencing the Mental Health Consequences of Climate Change in Canada. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(9), 1583.

Social capital and a sense of community protect mental health in a changing climate.

- Social capital refers to the networks and resources of support.

- A sense of community refers to the feelings of belonging.

Both social capital and a sense of community are of paramount importance in post-disaster recovery, even when compared with economic or other types of assistance.

5 Ways Communities are Coping with Climate Anxiety

- Action-oriented toolkits

- Talk therapy

- Meditation

- Psychological first aid

- Mental health first aid

- Peer-to-peer support

These responses facilitate recovery, hope, and activism.

Policy and Practice Interventions

Policies

- Improve access to, and funding for mental health care.

- Assistance to reduce economic strain from climate hazards.

Practices

- Develop climate resilience plans that address psychological and social well-being.

- Conduct climate change and health assessments that examine the mental health effects of climate and adaptation options.

Medical Practices

- Specific therapies, behavioral interventions, or medications provided by mental health care professionals.

- Distribution of resource guides to the public on the mental health effects of climate change.

Individual Practices

- Spend time in nature.

- Connect with community.

- Engage in activities and active transportation (walking or biking) to improve mood and enhance physical health.

- Active transportation to support physical and mental health while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Well-designed greenhouse gas mitigation and adaptation actions to address climate change can produce significant health co-benefits, including benefits to mental health.

- Increase opportunities in a community for active transportation (e.g., walking, jogging, and biking) can reduce depression and improve mood.

Programs that support broader mental health needs that are supportive for people experiencing distress related to climate change:

Health Canada is building the capacity of health authorities in Canada to reduce risks from climate change, including those on mental health. For example, the Centre intégréde Santé et de services sociaux(CISSS) de Chaudière-Appalachesis leading a project to assess and support the health systems capacity of 2 CISSS pilot regions (Chaudière-Appalachesand Bas-Saint-Laurent) to prevent the negative impacts on mental health and psychosocial well-being of populations exposed to extreme climate events.

In December 2020, the Government of Canada committed to developing Canada’s first National Adaptation Strategy and Federal Action Plan. There are five Advisory Tables, including one on Health and Well-being that integrates climate change and mental health considerations.

- Dedicating chapters on mental health in Government-led National Climate Change and Health Assessments

- Research leaders (Australia, U.S.A., Canada, UK)

- Professional Psychiatric Networks:

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance (U.S.A, and Canada)

- UK Health Alliance on Climate Change

- Policy statements from health organizations:

- American Association of Public Health policy statements related to climate change and mental health (Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change on Mental Health and Well-Being.

- Briefing Papers for Policy Makers:

- Network of Care: Climate Psychiatry Alliance

- Training: International Transformational Resilience Coalition (ITRC) Workshops

- Guidance: Emotional resilience toolkit for climate work

- Nature-Based Therapies: Forest Bathing

- Social-Environmental Prescribing: PaRXPark prescriptions

- Group-based interventions

- Spiritually-base interventions

- Online forums

References

- Institute for Environment and Human Security of the United Nations University in 2015

- McAuliffe, M., Khadria, B., & Celine Bauloz, M., N. (2020). World migration report 2020. International Organisation for Migration.

- Gibson, K., Haslam, N., Kaplan, I. (2019). Distressing encounters in the context of climate change: Idioms of distress, determinants, and responses to distress in Tuvalu. Transcultural Psychiatry. 56(4) 667-696

- Gleick PH. Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria. Weather ClimSoc. 2014;6(3):331-340. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

- Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC IntHealth Hum Rights. 2015. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

- Schwerdtle P, Bowen K, McMichael C. The health impacts of climate-related migration. BMC Med. 2017. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0981-7

- Albrecht G. Chronic environmental change: Emerging “psychoterratic”syndromes. In: WeissbeckerI, ed. Climate Change and Human Well-Being. New York: Springer; 2011.

- Cunsolo A., Ellis NR. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat ClimChang. 2018. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

- Clayton, S., (2020). Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 1022263, doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.