- Optional Reading

- Moore, Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 9th ed., Viscera of thoracic cavity section through Clinical box: Pleurae, lungs, and tracheobronchial tree; The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, 11th ed., chapter 10.

Pleura and pleural sacs

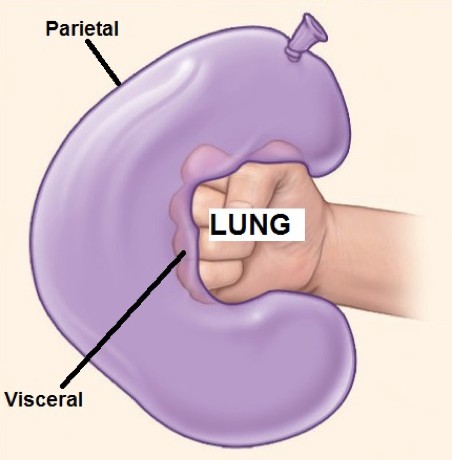

Pleura is a serous membrane associated with the lungs. Pleura comes in two varieties:

Visceral pleura invests each lung; in fact, it forms the outermost layer of the organs themselves. It is snugly adherent and difficult to remove. Being structurally part of the lungs, it is derived from splanchnic mesoderm and supplied by visceral nerve fibers.

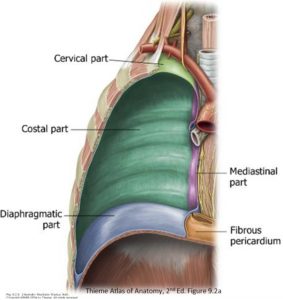

Parietal pleura lines the thoracic cavity. Since it is part of the body wall, it is derived from somatic mesoderm and supplied by somatic nerves. It is divided into named parts based upon the structures it covers:

-

- Costal pleura is glued to the inside of the anterior, lateral, and posterior thoracic wall.

- Diaphragmatic pleura covers the superior surface of the diaphragm.

- Mediastinal pleura covers the lateral sides of the mediastinum.

- Cervical pleura (a.k.a. cupula) projects above rib 1, where it forms a dome above the apex of the lung.

The four parts of the parietal pleura form a continuous layer. Sharp transitions occur where one part changes direction to become another: for example, where costal pleura leaves the anterior thoracic wall to become mediastinal pleura.

The visceral and parietal layers of pleura are also continuous. This continuity occurs where the mediastinal pleura forms a cuff around the structures entering and leaving the lung (root of the lung), and from here, doubles back onto the surface of the lung to become visceral pleura. The parietal and visceral layers of pleurathus form a closed sac around the lungs = the pleural sac. Within the sac is the pleural cavity, which contains a small amount of lubricating serous fluid that allows the parietal and visceral pleurae to slide across each other without friction during respiration.

Pleural recesses

In most areas, the pleural cavity is a “potential” space where the visceral pleura on the lungs touches the parietal pleura on the body wall, with a thin layer of serous fluid in between.

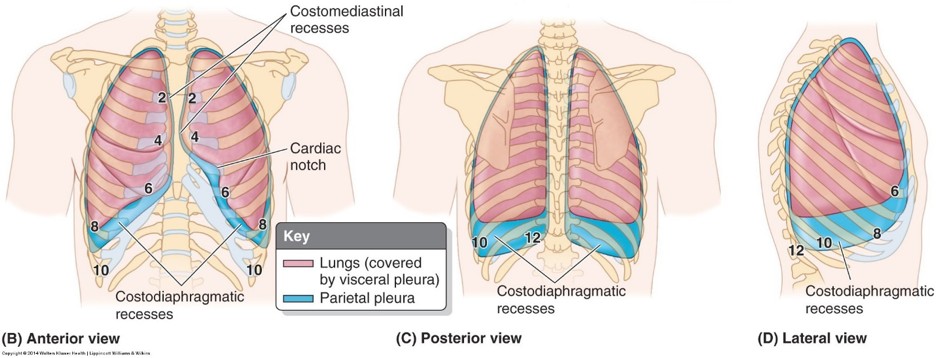

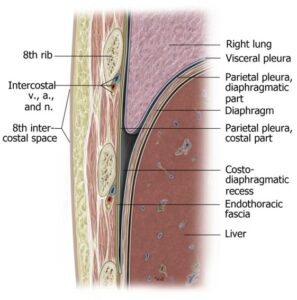

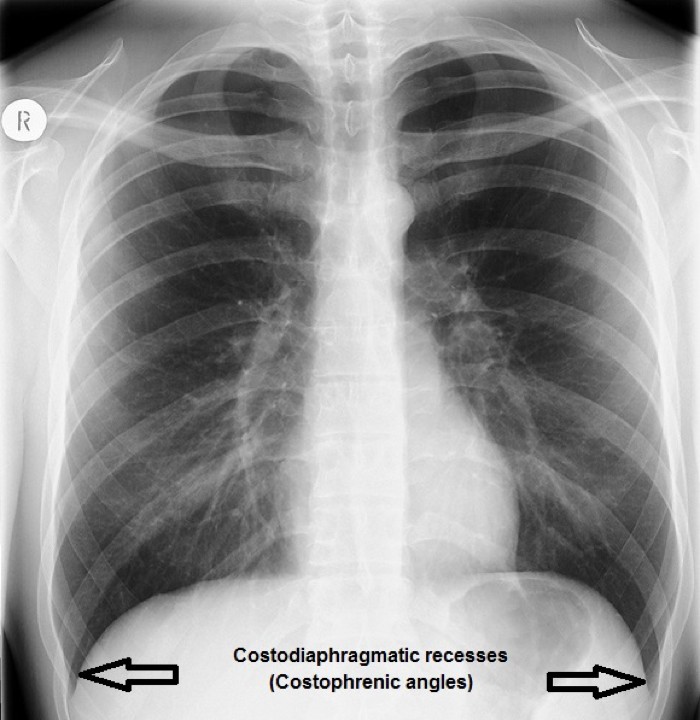

Below the lungs however, deep recesses of the pleural cavity are formed where the costal pleura leaves the chest wall at a sharp angle and curves up onto the upper surface of the diaphragm. These are the costodiaphragmatic recesses. They are deepest posteriorly, extending as far down as the 12th rib. Duringexpiration and quiet breathing these recesses exist, but during deep inspiration the inferior borders of the expanding lungs move down to fill the recesses. In a normal chest radiograph, these recesses should appear as sharp acute angles, so clinicians refer to them as the “costophrenic angles.”

Clinical correlation

A pleural effusion is an accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity. It can be caused by lung pathology (viral infection or bacterial pneumonia) or by systemic factors (heart failure, cirrhosis). Pleural effusions make it difficult to breathe since they restrict expansion of the lungs during inspiration.

In the anatomic position, pathological accumulations of fluids (exudates, blood, pus) can fill the costodiaphragmatic recesses. On a radiograph, radiolucent air density is replaced with a hazy radiopacity that obscures the sharp margins of the recesses.

Clinicians call this “costophrenic angle blunting.”

Thoracentesis (pleural tap) is a procedure that can be used to remove abnormal contents of the costodiaphragmatic recess using a hollow-bore needle placed through the chest wall along the upper border of a rib.

Nerves and vessels of the pleurae

- The parietal and visceral pleurae have identical constructions; however, they have different embryonic origins, so they have different nerve and blood supplies.

- Parietal pleura shares nerve and blood supply with the structures it covers. These are somatic nerves, so pain from the parietal pleura is sharp and can be discretely localized.

- Costal and cervical pleura: Supplied by intercostal nerves and vessels.

- Diaphragmatic and mediastinal pleura: Phrenic and intercostal nerves; intercostal and pericardiacophrenic vessels (branches/tributaries of the internal thoracic vessels).

- Clinical: The phrenic nerves are composed of fibers derived from spinal nerves C-3, C-4, and C-5. Therefore, irritation of regions of pleura supplied by the phrenic nerves refers pain to the C-3, C-4, and C-5 dermatomes—these are located on top of the shoulders.

- Visceral pleura is part of the lung. It is supplied by visceral afferent nerve fibers and said to be insensitive to pain.

Surface projections of the pleural cavities and lungs

In quiet breathing, the inferior borders of the lungs remain about two ribs higher than that of the inferior extent of the parietal pleura in the costodiaphragmatic recesses. Use the “rule of twos” to locate the positions of lung and parietal pleura on the body wall, as illustrated in Table 37.1.

Table 37.1.

|

|

Mid-clavicular line (anterior) |

Mid-axillary line (lateral) |

Midpoint of scapula(posterior) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Inferior extent of lung (visceral pleura) |

Rib 6 |

Rib 8 |

Rib 10 |

|

Inferior extent of parietal pleura in costo- diaphragmatic recess |

Rib 8 |

Rib10 |

Rib 12 |

Thought question

Why would knowing the two-rib gap between lung and parietal pleura be clinically useful?

Movements of respiration

One of the functions of the chest wall is to generate the forces needed for adjusting the volume of the thoracic cavity, thus allowing air to move into and out of the lungs (inspiration and expiration).

- Inspiration

- Expiration

Inspiration is an active process requiring contraction of muscles attaching to the rib cage. These produce movements that affect the size of the thoracic cavity in three dimensions:

-

- The anteroposterior dimension is affected by elevation or depression of the upper ribs. Elevation of the ribs occurs with contraction of the external intercostal muscles. Since the anterior ends of the ribs attaching to the sternum are inferior to the posterior parts attaching to the vertebral column, elevation of the upper ribs moves the sternum forward and upward, like the motion of an old-fashioned “pump handle.”

- The transverse (lateral) dimension is affected by elevation or depression of the lower ribs. Elevation is due to contraction of the external intercostal muscles. The lower ribs are arranged as loops, with their middle portions lower than their anterior and posterior ends. Elevation of these ribs swings their middle portions laterally, like the metal handle on a bucket of paint (“bucket handle” movement).

-

- The vertical dimension is affected by elevation and depression of the diaphragm. When contracted, the diaphragm flattens and lowers, increasing the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity. Relaxation of the diaphragm causes it to elevate, reducing the volume. The movements of the diaphragm are the most important factor in altering the volume of the thoracic cavity (accounting for 2/3 of the volume change).

Expiration is mainly passive in normal breathing, involving elastic recoil of the lungs and body wall after they have been stretched during inspiration. Forced expiration is accomplished by recruiting the internal intercostal muscles to depress the ribs and muscles of the abdominal wall to increase intra-abdominal pressure and cause the diaphragm to elevate.

Clinical correlation

Any muscles that attach to the ribs can potentially move them and act as accessory muscles of respiration. The scalene muscles in the neck (attached to ribs 1 and 2) and the pectoral muscles in the chest (when the arms are fixed) can be recruited to elevate the ribs. Patients in respiratory distress will often grasp their lower limbs or lean on their elbows to immobilize their arms so that the pectoral muscles can assist in inspiration.

The pressure within the closed pleural cavities is slightly below that of the atmosphere. Atmospheric pressure within the lungs, being higher than the “negative pressure” in the pleural cavity, keeps the visceral pleura against the parietal pleura. When the body wall and parietal pleura move, visceral pleura moves with it and air enters the lungs, inflating them within the expanding thoracic cavity.

Clinical correlation

Atmospheric air entering the pleural cavity produces a pneumothorax.

This can be caused by a penetrating injury to the chest wall but most often they are spontaneous, occurring without a known cause, perhaps because of a ruptured “bleb” on the surface of the lung. Air in the pleural cavity destroys the natural pressure gradients, preventing the lung from inflating (collapsed lung). If the compromised pleural cavity continues to fill with air, the increasing pressure could force the organs in the mediastinum to the unaffected side (mediastinal shift), compressing the heart and other lung. This emergency condition is called a tension pneumothorax.

Lungs

- The lungs are paired, cone-shaped organs that function in exchanging gases between atmospheric air and blood.

- Air enters the lungs through a series of branching air tubes called the bronchial tree.

-

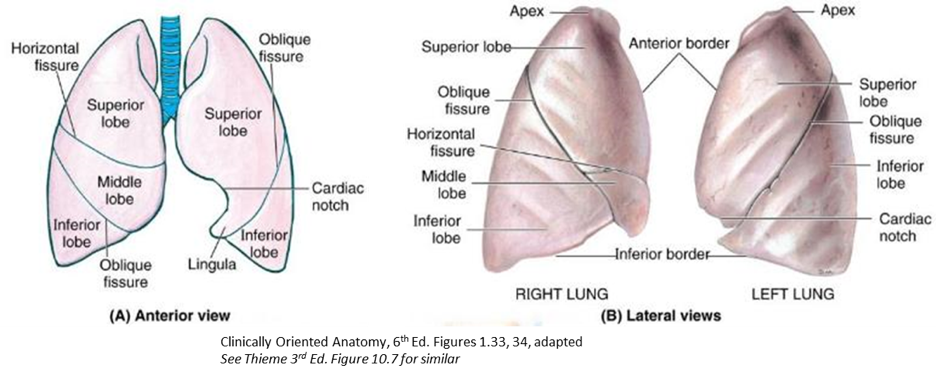

The lungs are lobulated structures:

The lobes are separated by fissures: oblique and horizontal on the right; oblique on the left.

Because the oblique fissures slope downward and forward, the upper and middle lobes are anterior to the lower lobes. The lower lobes are posterior. This has consequences for auscultation. Clinicians listen to lung sounds from the lower lobes though a stethoscope placed on the patient’s back.

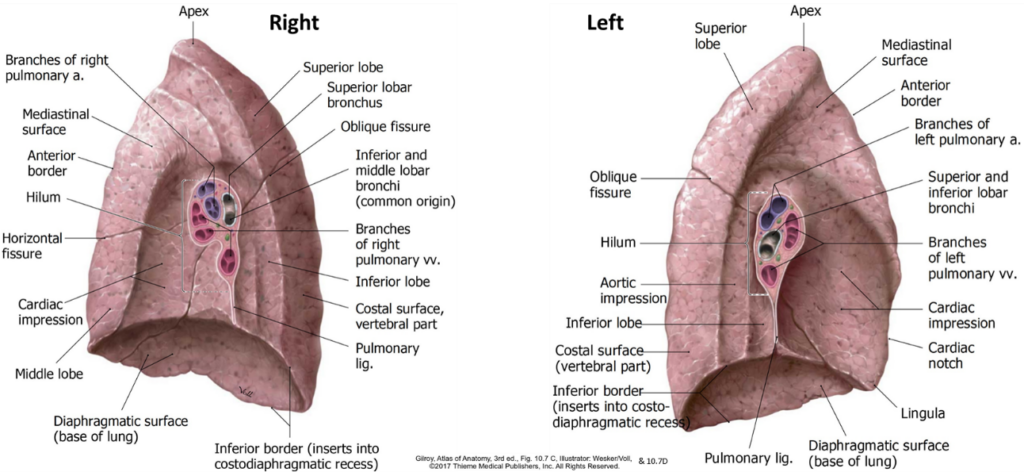

External anatomy of the lungs

- The apex projects above the clavicle; the base faces the diaphragm.

- Three surfaces: costal, mediastinal, and diaphragmatic.

- Two sharp borders: anterior (where costal and mediastinal surfacesmeet) and inferior (where diaphragmatic and costal surfaces meet).

- Left lung special features:

- Lingula (Latin = tongue): In left superior lobe, counterpart to the right lung’s middle lobe.

- Cardiac notch: Indentation to accommodate the heart.

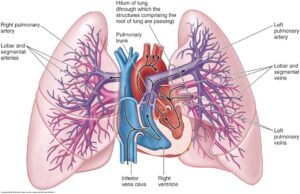

- Root of the lung: The collection of structures that enter/exit the lung: main bronchus, pulmonary artery, superior and inferior pulmonary veins, autonomic nerves, and lymphatic vessels.

- Suspends the lung from the mediastinum. It is the “wrist” of the “fist in a balloon” analogy. The root is surrounded by a “cuff ” of mediastinal pleura.

- Pulmonary ligament: A redundant double layer of pleura hanging below the root. It resembles a baggy shirt sleeve around the wrist. It supports the lung and allows for expansion of blood vessels, avoiding constriction within the cuff of pleura around the root.

- Hilum: The depression on the medial surface of the lung where the root structures enter and leave the lung. It is the “portal” to the lung.

- Contains many bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes.

The arrangement of root structures is different in the hila of the two lungs. However, a surgeon approaching the lung root from the anterior will normally encounter the superior pulmonary vein first.

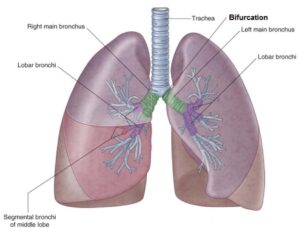

Tracheobronchial tree

- Trachea

- Distal continuation of the larynx, passing from the neck into the superior mediastinum.

- Can be palpated in the anterior neck, just above the suprasternal notch.

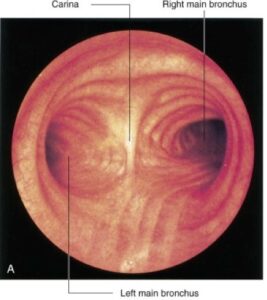

- The trachea bifurcates into the right and left main bronchi at the level of T-5 or T-6.

- The airway of the trachea is held open by C-shaped hyaline cartilage rings. The last tracheal ring forms a prominent midline ridge called the carina (Latin = keel of a boat), seen internally at the bifurcation. This is an important landmark for bronchoscopy.

- Main (principal) bronchi

- These are the first order of branching air tubes in the bronchial tree. They are kept open by rings or plates of hyaline cartilage. The left main bronchus enters the left lung at the hilum. The right main bronchus usually divides into the right upper lobe bronchus and the interlobar bronchus before entering the lung.

Clinical correlation

An inhaled foreign body is more likely to lodge in the right main bronchus than the left. This is because the right main bronchus is shorter, wider, and more vertical than the left—and thus more in line with the trachea.

- Lobar bronchi

- These are the second order of branching air tubes. They supply the lobes of the lung.

- 3 on the right:

- Right upper lobe

- Middle lobe

- Right lower lobe bronchi.

- The middle and lower lobe bronchi branch from an intermediate bronchus referred to as the interlobar bronchus.

- 2 on the left:

- Left upper lobe

- Left lower lobe bronchi

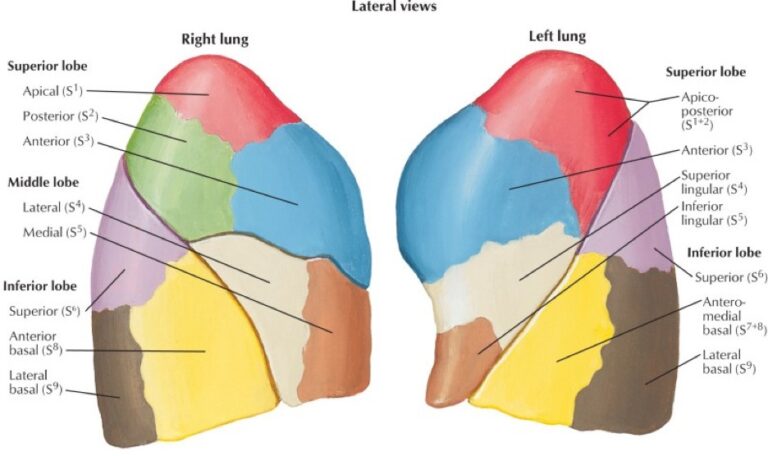

- Segmental bronchi

- These are the third order of branching air tubes. About 10 segmental bronchi in each lung.

- The regions of lung tissue aerated by segmental bronchi are called bronchopulmonary segments (BPSs). These are like “mini lungs,” supplied with air by third-order air tubes and with blood for gas exchange by third order branches of the pulmonary arteries. BPSs have clinical importance, since some diseases appear in the lungs in a segmental pattern. BPSs are separated by thin fascial planes, so surgeons can resect segments of lungs.

The lungs receive a double blood supply: One set of vessels for gas exchange/oxygenation (pulmonary vessels) and one set for the metabolic needs of the lung tissues (bronchial vessels).

Pulmonary arteries: Transmit poorly oxygenated blood

- Right and left pulmonary arteries (1 per lung): Bifurcate from the pulmonary trunk to the left of the ascending aorta.

- The left pulmonary artery is short and vertical. It enters the hilum of the left lung above the left main bronchus.

- The right pulmonary artery is longer and horizontal. It passes under the arch of the aorta. As it enters the hilum of the right lung, it divides into a right upper lobe artery and an interlobar artery. These are posterior to the right main bronchus.

- The branching pattern of the pulmonary arteries follows that of the air tubes.

- Ultimately give rise to pulmonary capillaries, which participate in gas exchange with the alveoli.

Pulmonary veins

- Two per lung: Superior and inferior. Carry oxygen-rich blood away from the lungs.

- Enter the left atrium of the heart.

Bronchial vessels

- Bronchial arteries (1 or 2 per lung) arise from the thoracic aorta or intercostal arteries. They follow the bronchial tree, branching in the same pattern. Supply the metabolic needs of the air tubes, supporting tissues of the lungs, and the visceral pleura.

- Bronchial veins drain into the azygos and accessory hemiazygos veins. They drain blood from the bronchial tree, but apparently not the visceral pleura. Venous blood from visceral pleura drains into the pulmonary veins. Odd.

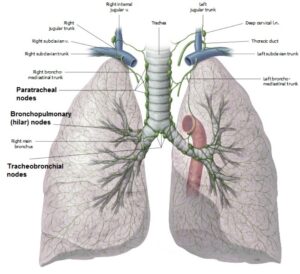

Lymph from the lungs percolates sequentially through the following nodes:

-

-

- Pulmonary nodes: located in the substance of the lung, along bronchi.

- Bronchopulmonary (hilar) nodes: Located in the lung hilum.

- Tracheobronchial nodes: Huge nodes located at or near the tracheal bifurcation.

- Paratracheal nodes: Located around the trachea and arch of the aorta.

- Lymph from paratracheal nodes enters lymph trunks in the thoracic cavity that drain upwards toward the base of the neck. Here the trunks enter the venous angles (= junctions of the internal jugular and subclavian veins). Variations occur often—sometimes the lymph trunks merge with the thoracic duct on the left or the right lymphatic trunk on the right.

-

The lungs are supplied by the left and right pulmonary plexuses. These contain a mixture of parasympathetic, sympathetic, and visceral afferent nerve fibers.The pulmonary plexuses are located on the left and right main bronchi and are carried into the lungs as the air tubes branch and re-branch.

Parasympathetic fibers are preganglionic and derived from the vagus nerves. They synapse on postganglionic cell bodies in ganglia in the walls of the bronchial tree. Functions:

-

-

Motor to smooth muscle in air tubes (bronchoconstriction)

-

Stimulate glands (mucous secretion)

-

Vasodilation of pulmonary vessels

-

Sympathetic fibers are postganglionic and derived from the sympathetic trunk. Functions:

-

- Relax smooth muscle in air tubes (bronchodilation)

- Inhibit glandular secretion

- Vasoconstriction of blood vessels

Visceral afferent fibers transmit both subconscious reflexive information and pain due to noxious stimuli.

Reflex information is carried to the CNS in the vagus nerves:

-

- Touch sensations for cough reflexes

- Stretch detection for limiting inspiration (Hering-Breuer reflex)

- Baroreceptors and chemoreceptors in pulmonary vessels

Pain signals (probably from visceral pleura and air tubes) are carried to the CNS via reverse sympathetic pathways, entering the spinal cord via upper thoracic spinal nerves.

Development of pleurae and lungs

Pleural cavities

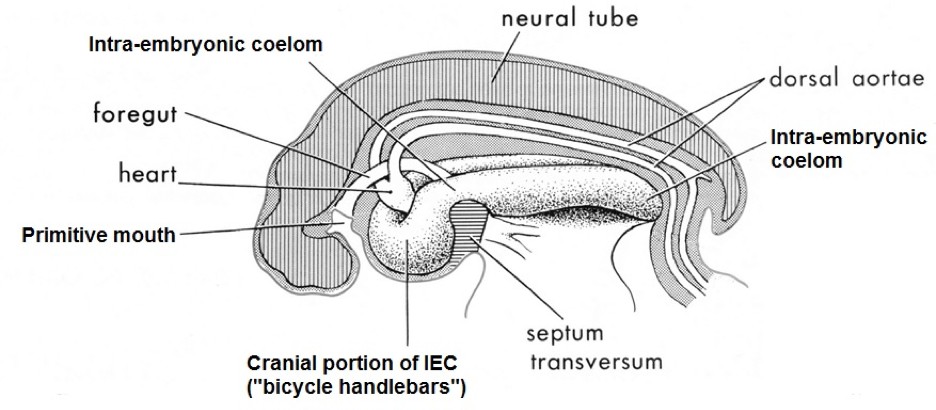

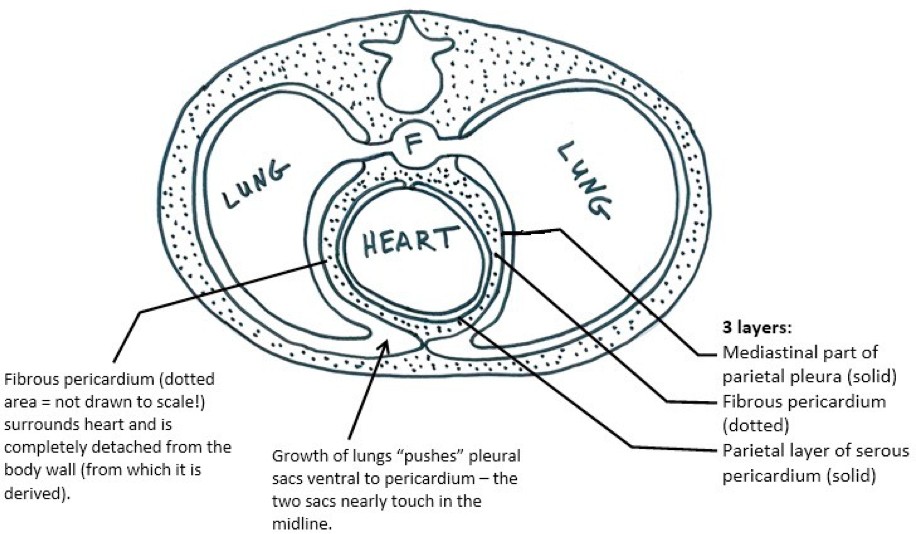

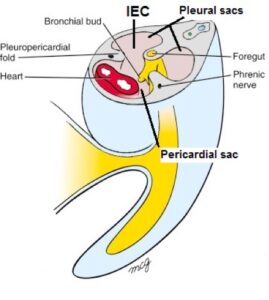

As described earlier in our embryology session, the primitive body cavity (intra-embryonic coelom = IEC) was lined by a primordial serous membrane. The serous membranes that surround the lungs are produced when the cranial portion of the IEC is partitioned into pleural and pericardial sacs.

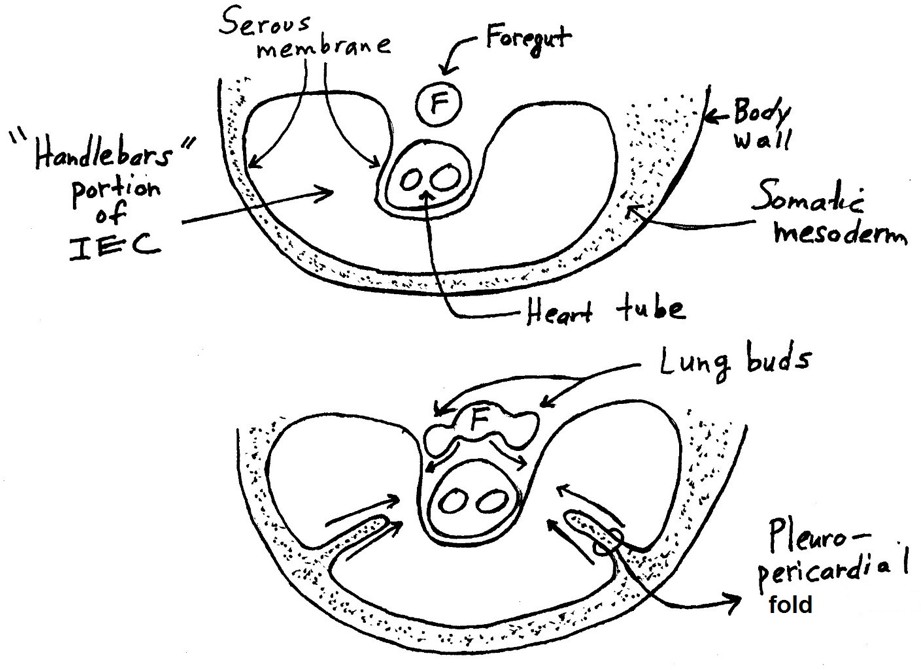

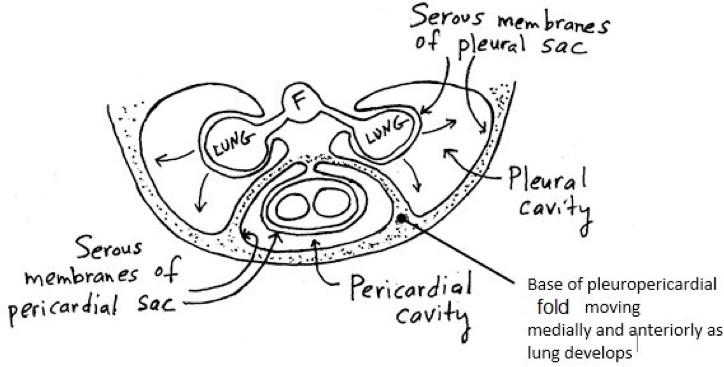

During the 5th week, left and right folds of somatic mesoderm are “pulled off” the inside of the lateral body wall in the cranial (“bicycle handlebars”) region of the IEC. Although these folds appear to migrate medially toward the midline on their own, it is the growth of the heart and associated movement of blood vessels adjacent to the IEC that produces these pleuropericardial folds. The folds grow toward the midline and eventually fuse posterior to the developing heart, partitioning the “handlebar-shaped” portion of the IEC into two posterolateral pleural sacs and a midline pericardial sac.

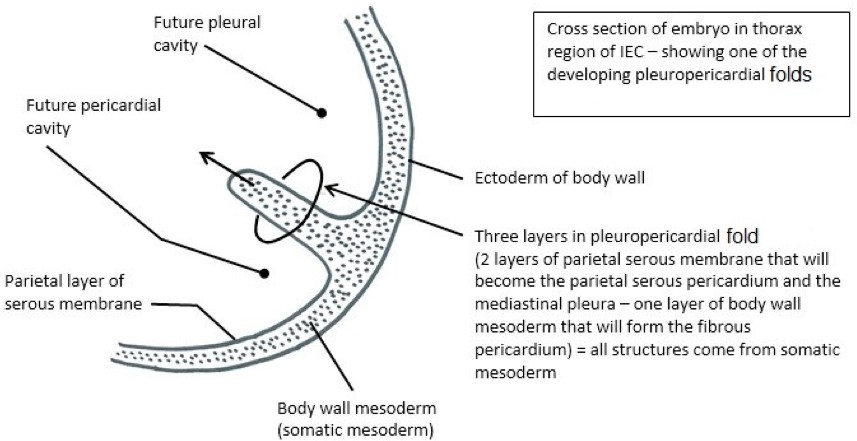

The primordial serous membrane lining the IEC is also pulled medially with the body wall mesoderm, making the pleuropericardial folds three-layered structures = two layers of serous membrane and a central core of body wall mesoderm (see Figure 37.17). The two layers of serous membrane give rise to the mediastinal portion of the parietal pleura (laterally) and the parietal layer of the serous pericardium (medially). The body wall mesoderm in the core of the triple-layer sandwich gives rise to the fibrous pericardium (outer part of the pericardium that surrounds the heart). The phrenic nerves are trapped in this mesoderm—in the adult they are thus tethered to the fibrous pericardium.

The drawings that follow are transverse sections of the folded embryo in the thoracic region, where the “bicycle handlebars” portion of the IEC is being partitioned by the pleuropericardial folds.

The pleuropericardial folds start out growing in a coronal plane. The lungs sprout from the foregut (F) and grow into the future pleural cavities, with a layer of serous membrane on them (the visceral pleura). Lung growth and expansion “uproots” the bases of the pleuropericardial folds (the parts attached to the inner body wall), causing them to progressively move anteriorly and medially, so that they get closer and closer to each other. Eventually they fuse to complete the pericardium around the heart and form the sternopericardial ligaments.

Note in the diagram that the fibrous pericardium (speckled) is derived from body wall mesoderm (thus it is a somatic structure) even though it is peeled away from it.

Take home message

The pleuropericardial folds form the “septum” that separates the pleural cavities from the pericardial cavity = the septum is made from the mediastinal pleura, fibrous pericardium, and parietal layer of the serous pericardium. Confirm this in the donors in the anatomy lab.

Summary

The pleuropericardial folds partition the cranial portion of the IEC (“bicycle handlebars”). Three serous sacs develop within the thoracic cavity. What are their names?

- Tying it all together

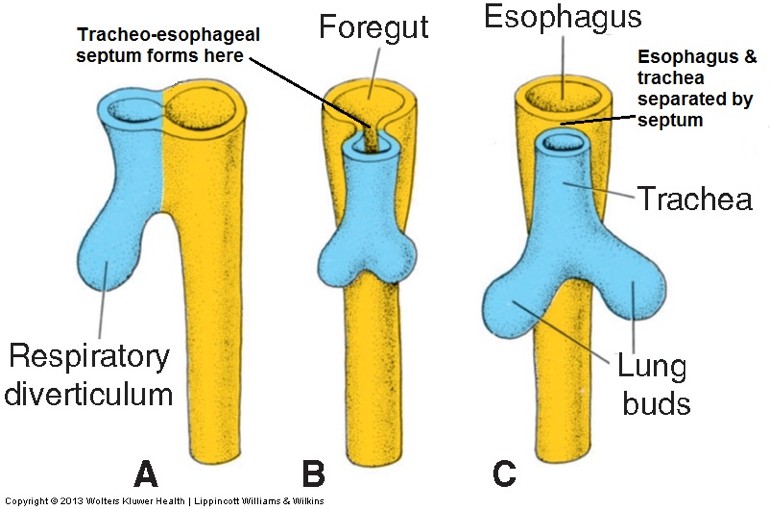

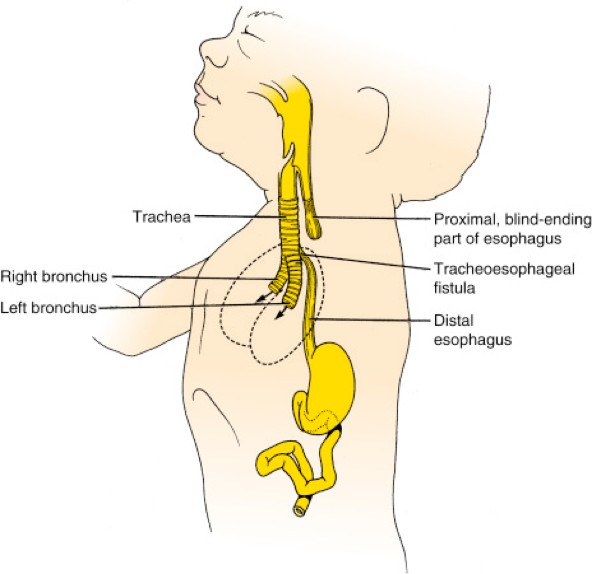

Development of the lungs and bronchial tree

The lining of the air tubes develops from endoderm, while the connective tissues, smooth muscle, vessels, and the visceral pleura develop from splanchnic mesoderm.

The development of the lungs is divided into five periods: embryonic, pseudoglandular, canalicular, saccular, and alveolar. There is disagreement among the major embryology textbooks as to which weeks of development fall into each period. We use the framework published in Larsen’s Human Embryology, 5th edition. What is agreed upon is that:

-

- The basic gross anatomy of the lungs develops during the first two periods. Thus, most congenital anomalies of the lower respiratory tract occur during this time.

- Production of surfactant and development of adequate pulmonary vasculature are the keys to survival of a prematurely born infant. These occur during the saccular period. Infants born before the saccular period (28 weeks) have a more difficult time surviving due to respiratory distress.

Table 37.2.

|

Period |

Time |

Highlights |

|---|---|---|

|

Embryonic |

4–6 weeks |

|

|

Pseudo- glandular |

6–16 weeks |

|

|

Canalicular |

16–28 weeks |

|

|

Saccular |

28–36 weeks |

|

|

Alveolar |

36 weeks–term |

|

- Tying it all together with Acland

- Additional detailed videos

- 3.2.5 Plural cavity, pleura.

- 5.1.12 Pleura, trachea, esophagus. (Pleural seal, parietal pleura seen from outside, and expansion and contraction of the lungs only.)

- 3.2.6 The diaphragm. (Diaphragm from below, line of origin, and action only.)

- 3.2.7 Muscles of inspiration.

- 3.2.8 Muscles of expiration.

- 5.1.11 Lungs.

- 5.1.12 Pleura, trachea, esophagus.

- 3.2.14 Nerves of the thorax. (Specifically: phrenic nerves, vagus nerves, and sympathetic trunk.)