Two important events occur during Week 3:

- The process of GASTRULATION, which forms the “germ” layers of the embryo

- Differentiation of the MESODERM (one of the germ layers)

Note

Development of the neural tube (future central nervous system) begins in Week 3, but carries over into Week 4.

Gastrulation

- Gastrulation is the process of converting the bilaminar embryonic disc into a trilaminar disc. Through this process, the three germ layers of the embryo are formed: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The germ layers provide all the primordial cells necessary for developing the human.

“It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life."

Developmental biologist Lewis Wolpert summed up the importance of gastrulation in 1986

Gastrulation begins with formation of the primitive streak

- A shallow groove develops in the midline on the dorsal surface (epiblast side) of the bilaminar disc. This is the primitive groove. The lateral edges of the groove are raised and filled with epiblast cells—similar to the edges of your sidewalk after you have shoveled snow. At the cranial end of the groove is a deeper depression called the primitive pit. The mound of epiblast surrounding the pit is the primitive node. The entire complex (groove + pit + node) is called the primitive streak. The formation of the primitive streak is a big-ticket item:

Clinical correlation

The primitive streak establishes the axis and the bilateral symmetry of the embryo. The cranial-caudal, left-right, and ventral-dorsal directions of the developing human are now specified. Normal left-right asymmetries in the body (e.g., heart on the left, liver on the right) are established during gastrulation when signaling molecules secreted by cells around the primitive node are distributed unevenly along the primitive streak, possibly due to current flows around the primitive node produced by the movement of cilia. Ciliary dysfunction during gastrulation may be an underlying basis for transposition of organs in the thorax and abdomen, a condition called situs inversus.

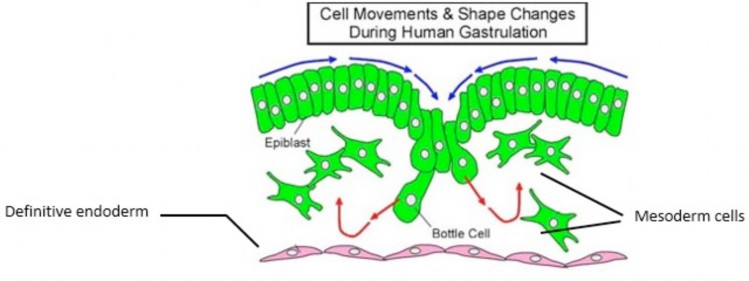

Epiblast cells proliferate and ingress

Figure 2.10 LANGMAN’ S MEDICAL EMBRYOLOGY, 12TH ED., FIGURE 5.3.

- Epiblast cells multiply and migrate into the primitive groove and primitive pit—it is thought that they crawl along with the help of foot-like processes called pseuodpods. The first cells to enter are shaped like flasks, so they are called “bottle cells.” See Figure 2.11.

- The first wave of ingressing epiblast cells displaces the hypoblast, replacing it with a new layer of flattened cells of epiblast origin—this new layer is called endoderm. Endoderm is an embryonic epithelium—its cells are joined together by tight junctions. Endoderm gives rise to the epithelial cells that form the inner lining of the digestive tract and its derivatives (air tubes, urinary bladder).

- Next, epiblast cells form a new germ layer dorsal to the endoderm—the mesoderm. Unlike the endoderm, the cells of the mesoderm are loosely organized and multipotent. Some mesoderm cells differentiate into muscle forming cells, while others become star-shaped cells that are loosely joined together. The later cells are called mesenchymal cells and they are part of a special tissue type found in embryos called mesenchyme = embryonic connective tissue that gives rise to connective tissue proper, cartilage and bone. Most of the mesenchyme in embryos comes from mesoderm.

- When the mesoderm and endoderm have formed, the remaining epiblast cells on the dorsum of the embryonic disc take on a new name: ectoderm. Ectoderm is an embryonic epithelium—it gives rise to the central nervous system and the outer layer of the skin (epidermis).

- Gastrulation creates a trilaminar embryonic disc—note that all three layers of the disc are derived from the original epiblast. Ectoderm and endoderm are embryonic epithelia whose cells are snugly joined together—while the mesoderm is a loosely organized tissue.

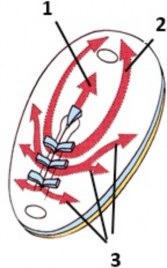

Gastrulation proceeds from cranial to caudal in a programmed sequence

Figure 2.11

The mesoderm layer spreads out in the middle of our “embryo sandwich.” The fate of mesoderm cells seems to be determined by when and where their precursor epiblast cells entered the primitive streak apparatus. Developmental biologists call this correspondence a fate map. The first mesoderm cells to develop are in the midline and cranial regions of the disc (1 and 2 in Figure 2.12). The primitive streak in the caudal region of the disc is the last to complete the process of gastrulation and produces mesoderm until the end of the 4th week (3 in Figure 2.12). Take home point = Gastrulation is completed sooner in the cranial region than in the caudal region. After gastrulation, the primitive streak regresses and disappears.

Clinical correlation

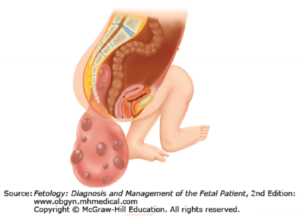

A teratoma (terato- = monster; -oma = tumor) is a tumor consisting of various tissues not normally characteristic of the region in which the tumor develops. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are among the most common tumors of newborns. They develop as a sac attached near the tailbone and are probably caused by a remnant of the primitive streak that failed to degenerate. Since the primitive streak contains pluripotent cells derived from the epiblast, the teratoma may contain various tissues, such as hair, teeth, bone, and nervous tissue. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are removed promptly after birth. Patients with large tumors are followed closely afterwards to monitor for recurrence and possible malignancy.

The embryonic disc remains bilaminar in two places

- In two areas, dimples appear where the ectoderm adheres firmly to the endoderm, with no intervening mesoderm. Cranially is the oropharyngeal membrane. Caudal to the primitive streak is the cloacal membrane. These sites indicate the end points of the future digestive tube. The membranes will later rupture to form the oral cavity and anus, respectively.

Differentiation of the mesoderm

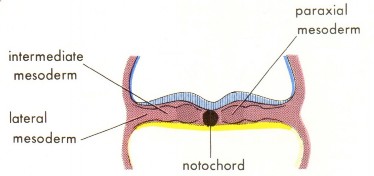

As mesoderm is formed in the embryonic disc, it organizes itself into rods and sheets of tissue between the ectoderm and endoderm. From medial to lateral, these are:

-

- notochord

- paraxial mesoderm

- intermediaste mesoderm

- lateral plate mesoderm.

See Figure 2.14.

Notochord

Some of the first mesoderm to become organized does so along the midline of the disc, extending from the primitive streak toward the oropharyngeal membrane. This mesoderm along the “axis” of the disc produces a solid rod of cells called the notochord. Formation of the notochord is an important event for several reasons:

- The notochord defines the axis of the embryo, and thus defines the orientation of the axial skeleton.

- It provides a rigid “backbone” to the developing embryo. Nobody likes a floppy embryo!

- It serves as a guide for development of the vertebral column. The vertebral bodies arise from paraxial mesoderm that coalesces around the notochord = ultimately replacing it with bone tissue. The notochord cells that survive between the developing vertebral bodies give rise to the nucleus pulposus, the central portion of the intervertebral disc.

- The notochord is an “inductor” in the early embryo = a signal-caller for the differentiation of certain primordial cells into definitive cells. For instance, it helps to signal the development and positioning of the neural tube (future central nervous system).

Paraxial mesoderm

- Paraxial mesoderm develops as long rods of tissue on both sides of the notochord. During the third week, the rods become segmented into blocks of tissue called somites, resembling large Tootsie Rolls®. The first somite appears about Day 20 in the head region of the embryo. The somites help establish the segmental organization of the trunk, so their development and migration are of vital importance in developing the human body plan.

- Approximately 44 somites initially develop. 31 of these (in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal regions) become associated with the 31 pairs of spinal nerves. The occipital somites do not associate with spinal nerves—they give rise to bone and connective tissues in the head.

- Each somite later develops subparts called myotome (forms skeletal muscles in the trunk and limbs), sclerotome (forms bones in the trunk = sternum, vertebrae and ribs), and dermatome (forms dermis of the skin in the back—don’t sweat the details).

Intermediate mesoderm

- Lateral to the paraxial mesoderm are smaller cylinders of mesoderm called intermediate mesoderm. These give rise to organs in the urinary and genital systems, kidneys and gonads.

Lateral plate mesoderm

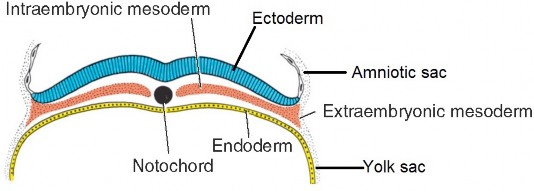

- The mesoderm between the intermediate mesoderm and the edges of the embryonic disc form bilateral flattened sheets called lateral plate mesoderm. At the edge of the embryonic disc, this “intra-embryonic”mesoderm is continuous with the “extra-embryonic” mesoderm (EEM) covering the amnion and yolk sac (“double bubble”).

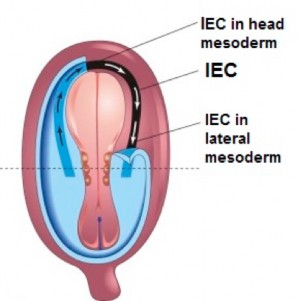

Head mesoderm

- Mesoderm also develops at the head-end of the embryonic disc, between the oropharyngeal membrane and the cranial edge of the disc. This “head” mesoderm is continuous laterally with the left and right lateral plate mesoderm.

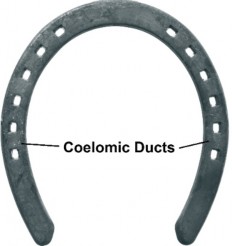

Intra-embryonic coelom (IEC) develops within the lateral plate mesoderm

- Near the end of the third week, spaces within the lateral plate and head mesoderms coalesce to form a larger cavity, the intra-embryonic coelom (IEC). This cavity is horseshoe-shaped, with limbs extending cranially along the left and right lateral portions of the embryonic disc. The limbs join together cranial to the oropharyngeal membrane within the head mesoderm, but not caudally. The walls of the IEC are lined by a primitive serous membrane. The IEC is the forerunner of the body cavities (thoracic and abdominopelvic) and the membrane lining the IEC will give rise to the serous membranes within the body cavities.

Figure 2.16 (left) HTTPS://PNGIMG.COM/DOWNLOAD/42842, CREATIVE COMMONS. (right) THE DEVELOPING HUMAN, 10TH ED., FIG. 4-9.

- The left and right limbs are called the coelomic ducts. The medial wall of each coelomic duct is bordered by intermediate mesoderm. Early on, their lateral walls are sealed by the fusion of the lateral mesoderm with the extra-embryonic mesoderm. During the 4th week, portions of the lateral walls disintegrate, and the coelomic ducts freely communicate with the chorionic cavity, allowing nutrient-rich fluid to reach the internal embryo.

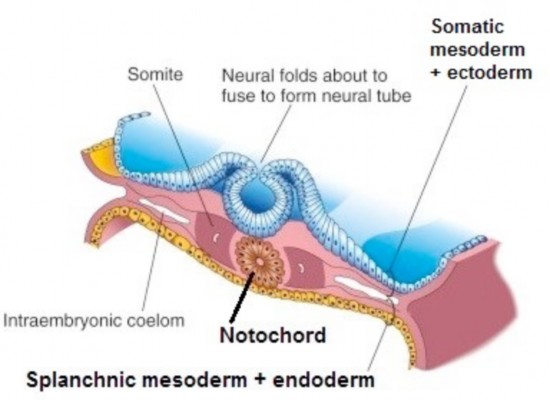

Formation of the IEC splits the lateral plate mesoderm into two layers: ventral and dorsal.

- Ventral

- Dorsal

The ventral layer of the lateral plate mesoderm is adjacent to the endoderm. It is called splanchnic mesoderm (splanchno– = viscera). After folding of the embryonic disc in Week 4, the splanchnic mesoderm and endoderm together are rolled into a tube rolled into a tube, forming the epithelium, smooth muscle, and connective tissues of the digestive tube. The primitive serous membrane lining the IEC, adjacent to the splanchnic mesoderm, will eventually become the outer layer of the digestive tube after folding = the visceral layer of serous membrane. The visceral layer of serous membranes in the body are derived from splanchnic mesoderm.

The dorsal layer of lateral plate mesoderm adjacent to the ectoderm is the somatic mesoderm (somato– = body, in this case, referring to the body wall). After folding of the embryonic disc, the somatic mesoderm + ectoderm form the skin and connectives tissues of the body’s outer shell = the body wall. Muscle building cells from somites invade this shell to form skeletal muscles. The serous membrane lining the IEC adjacent to the somatic mesoderm will ultimately form the inner layer of the body wall = the parietal layer of serous membrane. The parietal layer of serous membranes in the body come from somatic mesoderm.

Question

Note that the two layers of a serous sac (visceral and parietal layers of serous membrane) are derived from two different embryonic sources of mesoderm. How is this reflected in the innervations of the two layers of serous membrane?

Figure 2.17 is transverse section through the trilaminar disc. The location of the IEC between the two layers of lateral plate mesoderm is shown. Ectoderm is blue, endoderm is yellow.

Figure 2.17

Formation of the neural tube

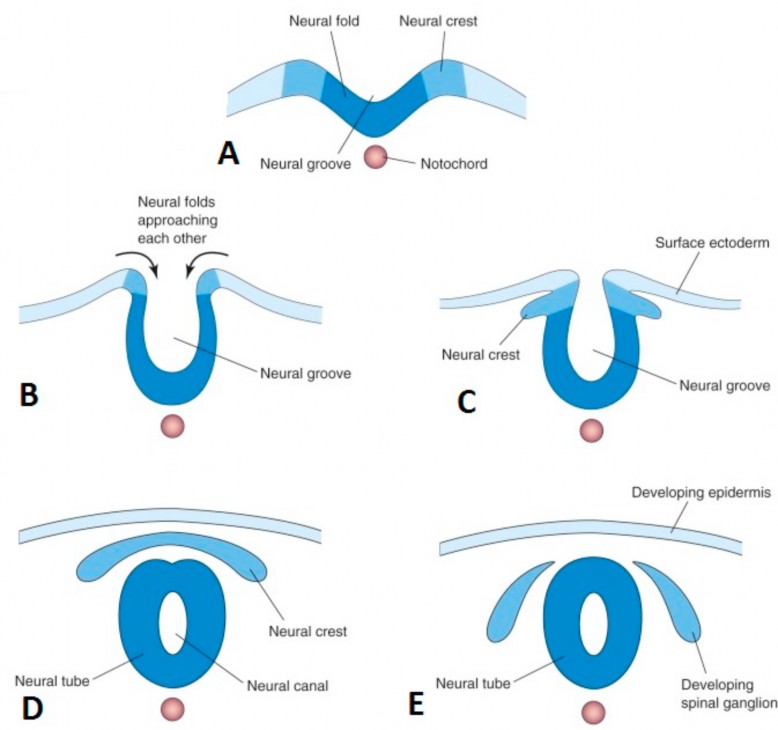

- Neurulation is the series of events in the 3rd and 4th weeks that form the neural tube = it will give rise to the brain and spinal cord. See Figure 2.18.

- Ectoderm cells in the midline transform into a thick, stratitifed neural plate that is broad in the cranial region and tapered caudally. It extends between the oropharyngeal membrane and the cloacal membrane.

- The lateral parts of the neural plate raise up on the dorsal surface of the embryo, producing two lips called neural folds. A neural groove is formed in the midline between the neural folds. The tips of the neural folds give rise to a very important population of cells, the neural crest.

- During the 4th week, the neural folds move closer together and fuse in the midline to form the hollow neural tube, which detaches from the surface and sinks beneath the ectoderm layer. The neural tube gives rise to the components of the central nervous system.

- During the process of forming the neural tube, the neural crests, special cells in the tips of the two neural folds, detach and sink into the embryo along with the neural tube. These two rods of neural crest cells are dorsolateral to the neural tube. Some of the neural crest cells form a series of segmentally arranged cell groups that associate with the somites lateral to the spinal cord. These cells produce the spinal ganglia (dorsal root ganglia). Spinal ganglia contain the cell bodies of sensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system. Other neural crest cells migrate widely throughout the body, forming a diverse group of structures, from tooth enamel to melanocytes (pigment cells in skin).

Figure 2.18 Neurulation. MOORE ET AL., THE DEVELOPING HUMAN, 10TH ED., FIGURE 4-10.

- The broad cranial part of the neural tube forms the brain and the narrow caudal portion becomes the spinal cord.

- The neural tube does not close simultaneously in all regions. Actually, fusion of the neural folds begins in the cervical region of the embryo and zippers away from this region in two directions: cranially and caudally. After zippering shut, the neural tube still has openings at its extreme cranial and caudal ends called the cranial and caudal neuropores, respectively. These should close during the 4th week.

Clinical correlation

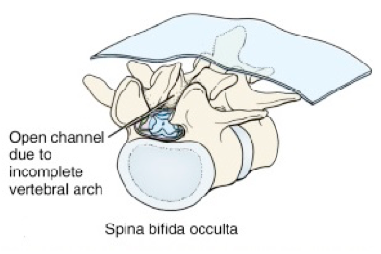

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are congenital anomalies of the central nervous system that result from defective closure of the neural tube during the fourth week.

Because the neural tube fails to close, or is slow to close, NTDs may also influence the tissues surrounding the CNS: meninges,skull, vertebral arches, muscles, and skin. Folic acid deficiency has been linked to NTDs, so pregnant women (and those thinking about becoming pregnant) are advised to take vitamins containing folic acid.

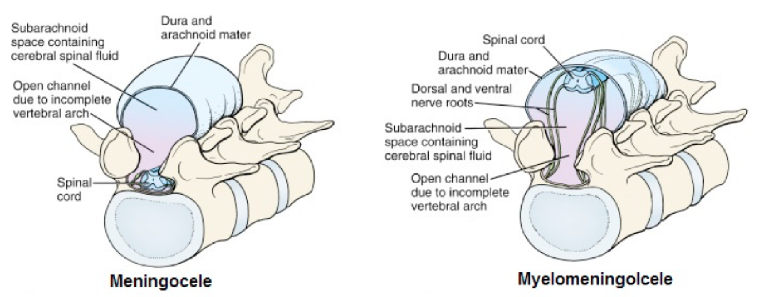

Neural tube anomalies that involve the vertebral arches are collectively known as spina bifida—this refers to non-fusion of the vertebral arches, producing incomplete halves = “bifid spines.”

Forms of spina bifida range from minor (spina bifida occulta) to clinically significant (meningocele, myelomeningocele, myeloschisis). The more severe forms (myelomeningocele, myeloschisis) can result in varying degrees of paralysis, loss of sensation in the lower limbs, and bowel and bladder problems. Spina bifida is caused by delay or failure of the caudal neuropore to close.

In the case of myeloschisis [schisis = a cleaving] (also called rachischisis in some texts) the caudal neuropore failed to close and the spinal cord in this region is nothing more than a mass of nervous tissue fused to the overlying skin, open to the world.

Failure of the cranial neuropore to close produces a catastrophic neural tube defect called anencephaly, where the brain and overlying skull fail to develop. This condition is incompatible with life.