With type II diabetes, keep it simple on the in-patient side.

With type II diabetes, keep it simple on the in-patient side.

Non-Insulin Medications

With room for thoughtful exceptions, when a patient is admitted to the hospital, stop the non-insulin medications.

Insulin

-

If the patient is already on insulin, and their blood sugar is relatively well controlled:

- Decrease the total dose by about 10%–20%. Make small adjustments based on the blood-sugar trend. This is because patients are often eating less and healthier food in the hospital.

- If the patient is already significantly hyperglycemic, continue heir home dose with additional correctional sliding-scale insulin.

- If the patient is not already on insulin, has mild diabetes, or a presenting blood glucose in the normal range, have them on an insulin sliding scale and see how things go.

-

If the patient is hyperglycemic or has more significant diabetes:

- Start them on basal and prandial insulin with additional sliding scale insulin. This can be done based on simple math using the patient’s weight.

- The initial total insulin dose should be 0.1–0.5 U/kg. This is a broad range.

- For an elderly, frail-appearing patient, I generally start with 0.2 U/kg.

- For a younger, obese patient, I may start with 0.3 U/kg.

- You can always increase the dose.

Most people will need about a 1:1 ratio of basal and prandial insulin.

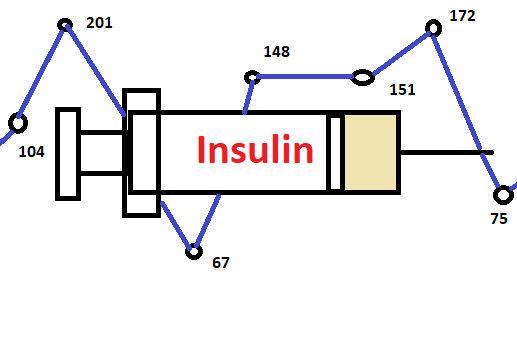

Let's say we admit a 100 kg diabetic patient and decide to stop his metformin and start him on 0.3 U/kg insulin on admission (that is 30 U of insulin total daily, 15 basal, 15 prandial (1:1 ratio)). So we can order 15 units of glargine once daily and 5 units of lispro TID with meals and an additional correctional sliding scale. This can be adjusted as necessary by looking at the glucose trend (when are the highs and lows happening). In general, make changes by adjusting the necessary insulin doses by about 10%–20% at a time.

Insulin Drip

Let’s say you have a lot of trouble determining a patient’s insulin needs, and our initial dose seems to be way off.

Although rarely necessary, it is an option to put the patient on an insulin drip so the nurses can follow an algorithm and quickly get the blood sugar into the goal range. The added benefit of the insulin drip is that you can look at the total insulin needs over a 12h–24h period (or until the drip has stabilized at a constant hourly rate). Use this to calculate the patient’s total daily insulin needs. They can eventually restart on basal and prandial insulin that approximates their true needs.

Blood Sugar

As for the blood-sugar goals, somewhere between 120 and 200 is usually adequate. Generally, guidelines advocate for somewhere within this range: 140–200, 120–180, etc. Overly tight glucose control in the hospital (for example, a goal of 95–120) is associated with patient harm.

Image credit: Eric Tanenbaum.