There are two conventional strategies to treat alcohol withdrawal:

- symptom-driven administration of benzodiazepines, and

- phenobarbital monotherapy.

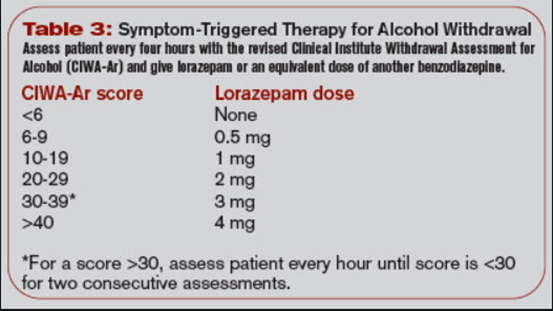

Patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) have relative GABA deficiency in their brains, and the mainstay of treatment is GABA agonism. Benzodiazepines (and barbiturates) are GABA agonists and are effective at treating alcohol withdrawal. To find the right dose of benzodiazepine, a protocol called CIWA was developed. Nurses will frequently assess patients for signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, based on the presence and severity of these signs and symptoms the patient is assigned a score, and then the patient receives a dose of benzodiazepines depending on that score. It is a decent treatment strategy and is superior to a non-symptoms driven benzodiazepine treatment approach.

Benzodiazepines

The benzo of choice is lorazepam because it is relatively fast acting and short acting, and it is not metabolized by the liver, which is often injured in patients who drink heavily. There is some room for debate about which benzo is best—diazepam may actually make more sense—but this discussion is beyond the scope of this website, and lorazepam is the conventional choice.

Some people augment this strategy with additional scheduled long-acting benzodiazepines (chlordiazepoxide) or with low-dose phenobarbital. I would not recommend doing either of these things routinely (although I do think there is a role for both in specific situations).

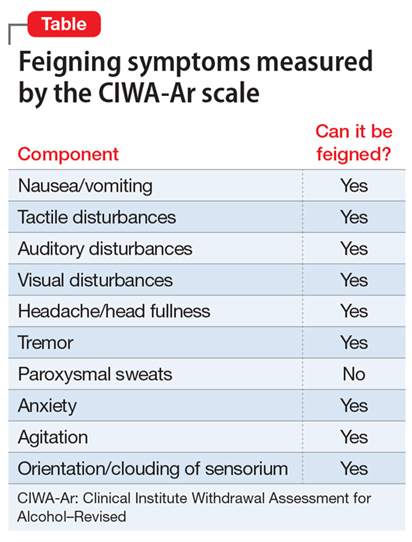

The trouble with CIWA is that many of the symptoms are subjective, and that benzodiazepines by themselves can cause delirium. Often in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal, patients end up stuck in the hospital with prolonged delirium, and after several days it becomes hard to tell if the patient needs an increased dose of benzos for undertreated alcohol withdrawal or if they need fewer benzos to help with non-alcohol withdrawal induced delirium. Below are a list of AWS symptoms and a sample dosing framework.

Phenobarbital

Then there is phenobarbital, an old medication that went out of fashion for AWS but is now back in style.

I like the way this website explains it—feel free to read through this article at your leisure for a more detailed understanding.

Basically, if you give a patient 10–15mg/kg of phenobarbital when they start withdrawing, the AWS is going to be mostly treated. The half-life of phenobarbital activity is around 100 hours, so it actually clears from the system at about the same rate that AWS resolves—sometimes one large dose of phenobarbital up front will be all the treatment the patient needs for the entire admission, which is great when it happens.

The key things to remember with phenobarbital are:

- It lasts a long time, there is no antidote, and if you accidentally give too much, the patient will stop breathing and will require intubation.

- It is unpredictably synergistic with benzodiazepines, so it is easier to accidentally overdose a patient who has already been treated with benzos, which is important given #1.

In General

For a patient who you expect to have relatively mild alcohol withdrawal (maybe, by looking at records from previous admissions), I recommend treating the patient with CIWA-score-driven lorazepam. For a patient who you expect to have severe alcohol withdrawal and prolonged delirium, give a loading dose of phenobarbital, and a few smaller doses early on if necessary to control symptoms.

Finally, I will add that sometimes these patients are very difficult to care for and behaviorally out of control. To avoid needing to keep these patients in restraints, adjuncts such as haloperidol, and atypical antipsychotics—often quetiapine—can be used. A dexmedetomidine infusion can also be helpful for patients who are in a sufficiently monitored environment for safe use of this medication (usually ICU or IMCU). Remember that these adjuncts do not really treat the AWS, preventing seizures and delirium tremens, but they do make it easier for the healthcare team to safely care for the patient.