These materials are based on the PowerPoint presentation by Anthony Gerber, MD, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, National Jewish Hospital.

What you'll learn

- Discover the climate change effects of ozone, PM2.5, and other ambient respiratory irritants on respiratory diseases such as asthma, COPD, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular, and allergic diseases.

- Analyze data related to hospital and ED usage for respiratory conditions as they relate to meteorological variables.

- Define how climate change makes air quality regulation more complex and difficult.

- Identify vulnerable populations and how health professionals can protect their patients and teach about risk mitigation, such as limiting outside work and recreation during poor air quality days.

- Understand how wildfires are impacted by climate change and their direct and indirect health implications.

- Describe how climate change increases the risk of complex disasters due to combined and cascading events (heatwaves followed by wildfires).

Mini Lesson: Air Pollution

In this mini lesson, you'll find:

- Case studies.

- Definitions.

- Review questions.

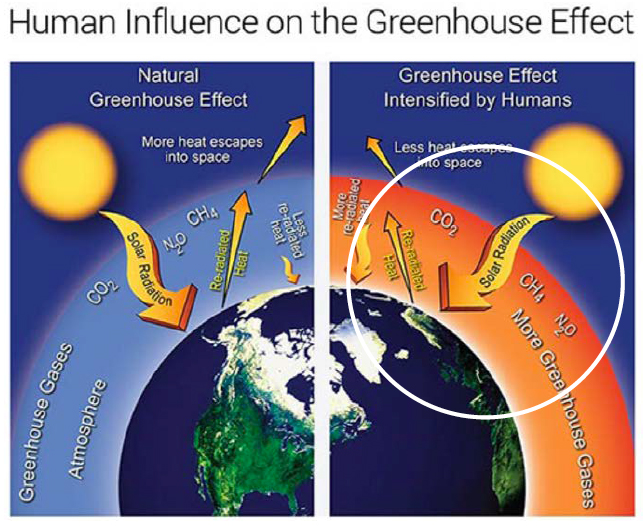

Multiple and Complex Interactions

There is well-established science on climate change and the gases in our lives that are the culprit. The human influence on the Greenhouse Effect include:

- Transportation

- Electricity

- Heating/Cooling

- Industrial process (Steel production, Cement mills)

- Fossil fuel extraction

- Specialty GHGs (CFCs)

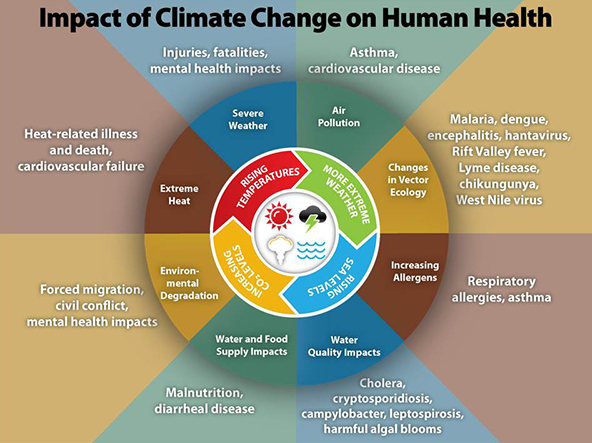

Impacts on Human Health

Ambient Indoor and Outdoor Air Pollution

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution is one of the greatest environmental health risks, including an increased risk of strokes, heart disease, lung cancer, and chronic and acute respiratory diseases.

However, research shows that people spend approximately 90 percent of their time indoors. A growing body of scientific evidence points to indoor air being more polluted than the outdoor air. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), people who are exposed to indoor air pollutants for a long period of time are susceptible to the same effects as outdoor air pollution.

Greenhouse gases (GHG, e.g., CO2, methane) are NOT typically classified as air pollutants based on traditional parameters. However, according to the EPA, worldwide greenhouse gases from human activity increased by 43% from 1990 to 2015. Emissions of carbon dioxide, which accounts for three-fourths of total emissions, increased by 51% over the same period.

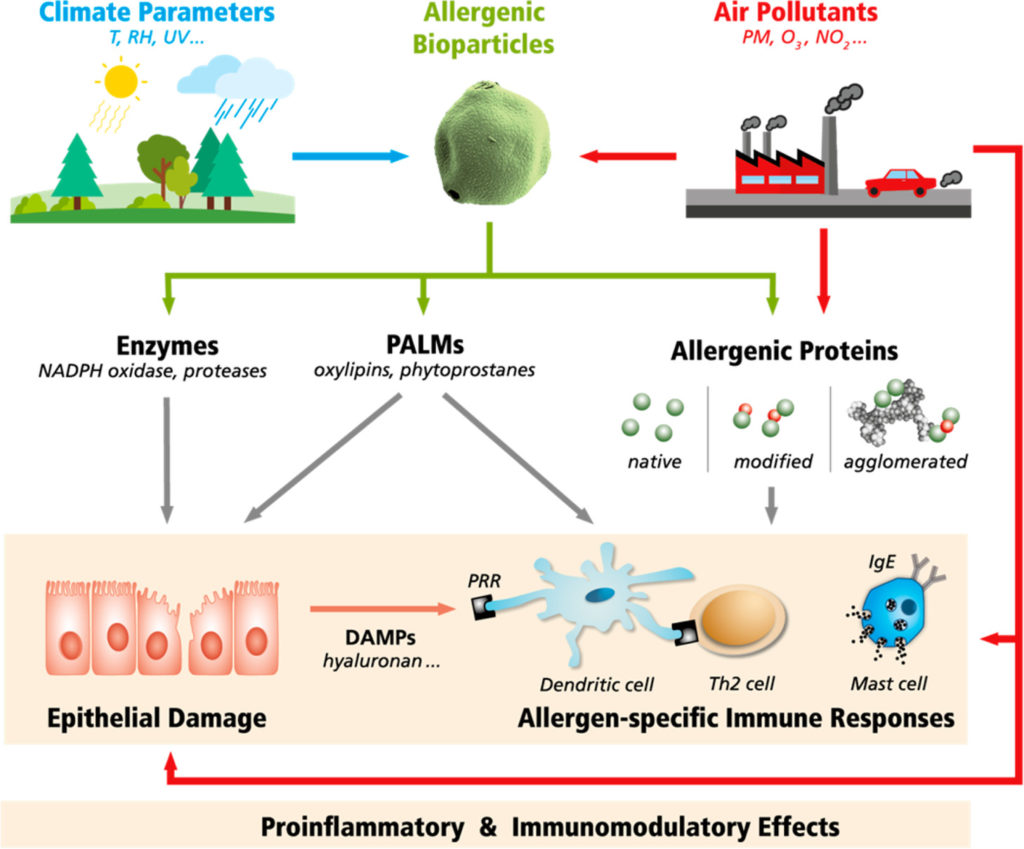

- As growing seasons extend, so does the risk of allergies.

- According to the EPA, increased CO2 can remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years.

- As the planet warms, plant ranges are expanded.

- Intense dust-wind events are contributing to the distribution of allergens.

- Increased flooding degrades indoor air quality through mold growth.

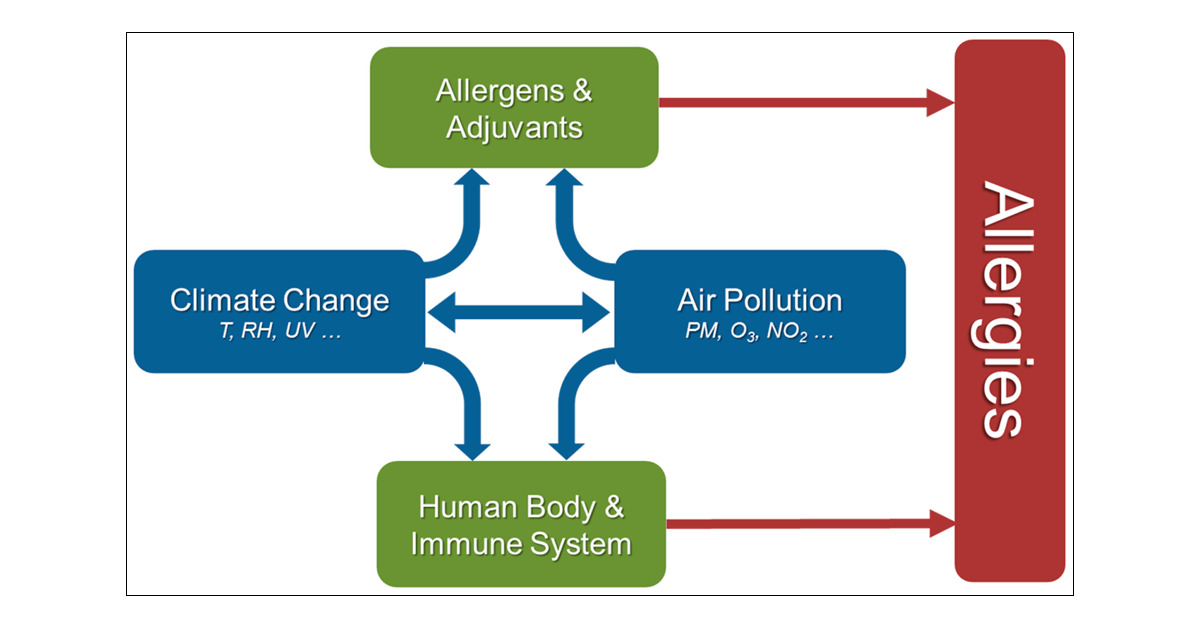

The interplay of air pollution and climate change promotes allergies by influencing the human body and immune system, as well as the abundance and potency of environmental allergens and adjuvants.

Regulating Air Pollution in the U.S.

- The EPA, under the clean air act, adopts science-based standards for levels of so-called “Criteria pollutants” (and air toxicants).

- PM 2.5 and (especially) ozone are the major criteria pollutants where standards are both becoming more stringent and remain significant in regions with non-attainment.

- States are tasked with implementing the federal standards through state-based regulations, often promulgated by volunteer commissions (e.g., California ARB, Colorado AQCC).

- It is impossible for state-based regulations to solve climate change. However . . .

- Climate change is making attainment of EPA standards more difficult.

- Reduction of ozone and PM pollution frequently has a GHG co-benefit.

-

If states don’t act on GHGs, who will?

The Underlying Science

GHG emissions, particulates, and ozone formation

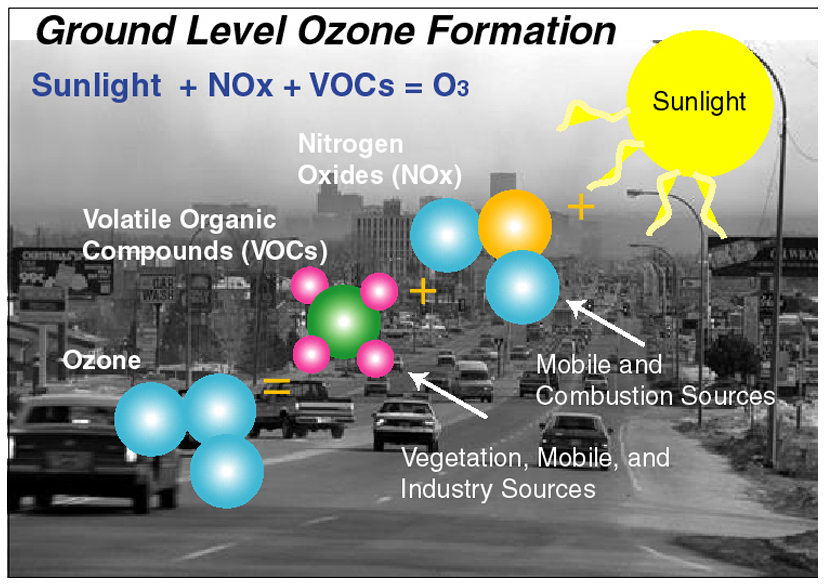

Ozone Formation and Climate Change

The image shows the underlying chemistry of ozone formation, which works best on hot days:

- Ozone formation requires sunlight.

- Typically, the sites of highest ozone do not directly overlap with production areas of ozone precursors.

- Chemical scavenging.

- Meteorology.

- Extreme heat from climate change directly impacts achieving NAAQS levels.

- Wildfire smoke provides ozone precursors.

Are these exceptional events or the new reality?

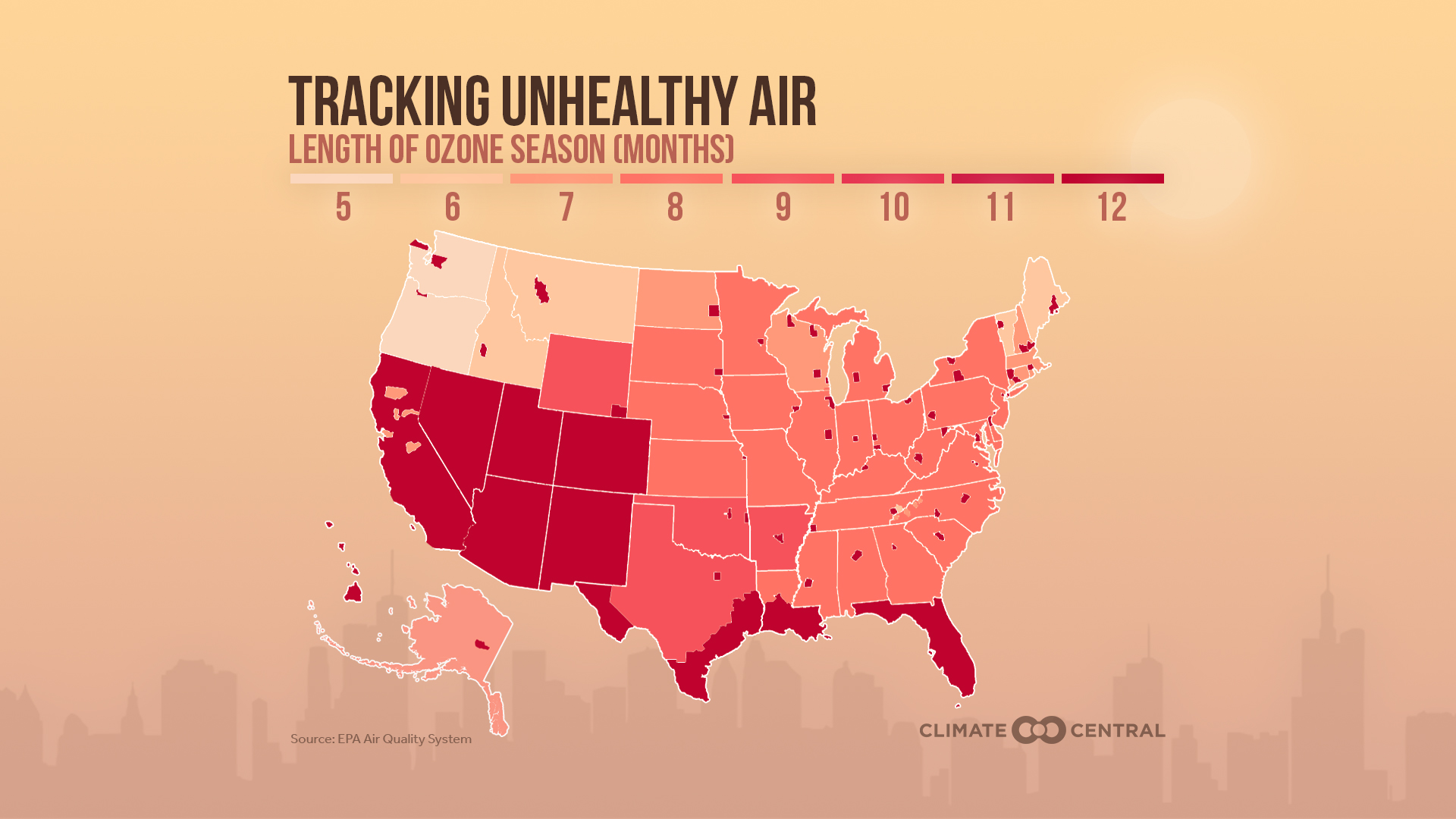

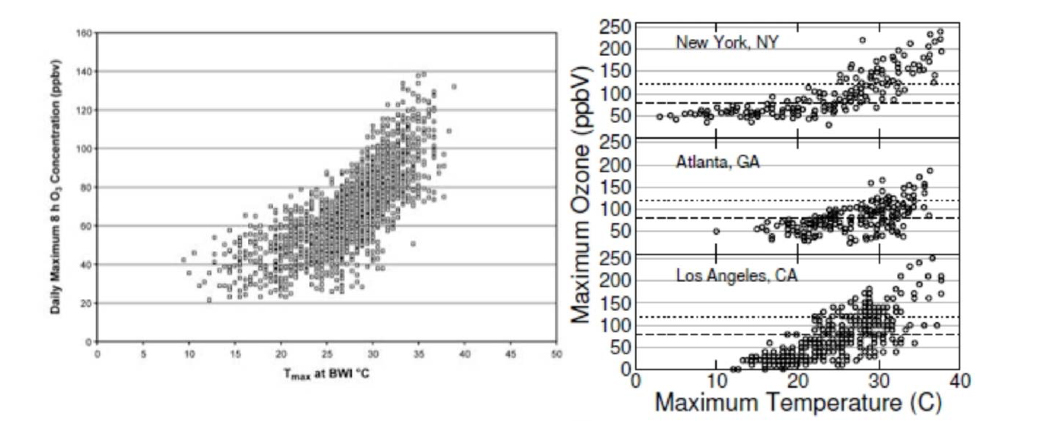

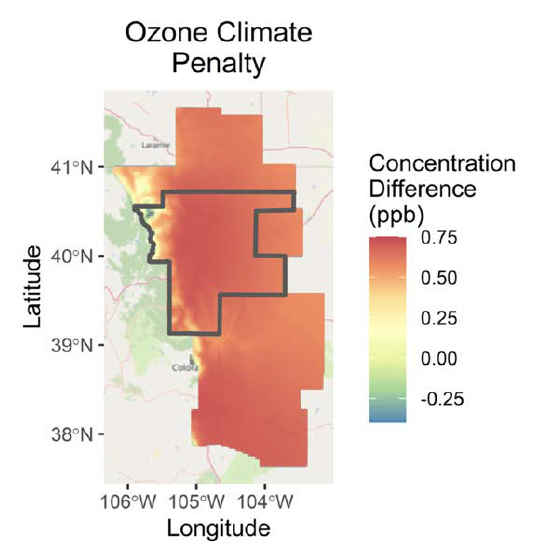

Climate Change Hotter Days More Ozone Days

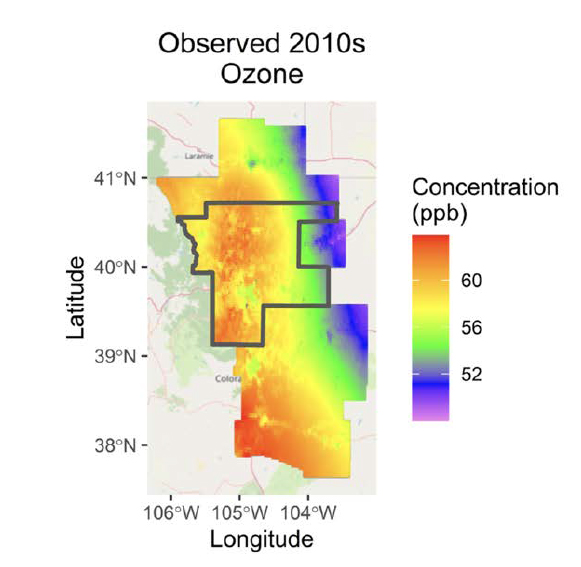

Ozone concentrations across the modeling domain during the high-ozone period (June–August) under the observed 2010s climate and the difference between the observed and counterfactual climates.

Source: Crooks JL, et al J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021 Sep 10. doi: 10.1038/s41370-021-00375-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34504294.

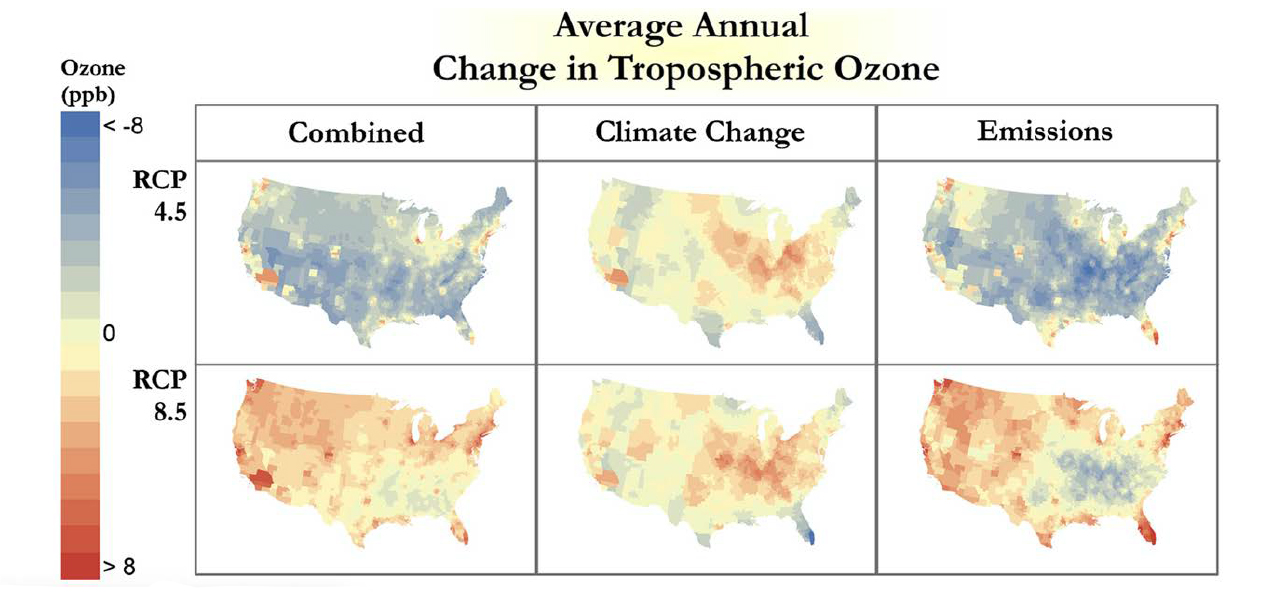

Average Annual Change in Tropospheric Ozone

Regulating Ozone Levels and Climate Change

- Hotter temperatures increase risk of high-ozone days.

- Climate change is increasing the number of hot days.

- A deeper reductions in ozone precursors are required to achieve a similar impact on ozone levels in comparison to a stable climate where average summer temperatures are constant.

- Example: Oil and Gas Leak Detection and Repair (LDAR) in Colorado.

- 2017: LDAR only required for larger production facilities.

-

2021: Annual LDAR for all facilities, monthly LDAR in areas of non-attainment for most facilities (note co-benefit GHG reductions).

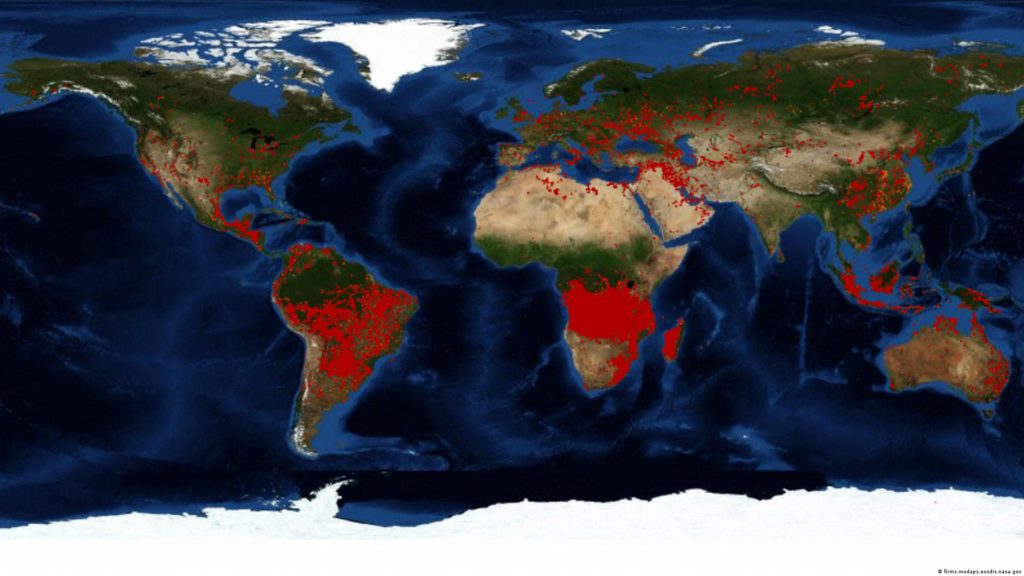

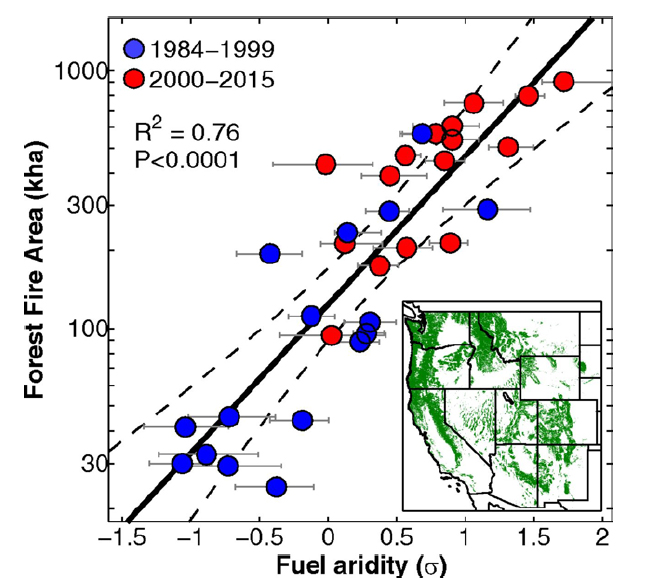

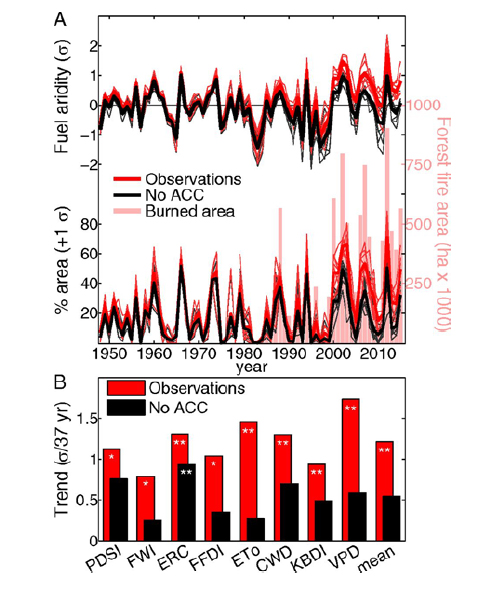

Climate Change Driving Wildfires

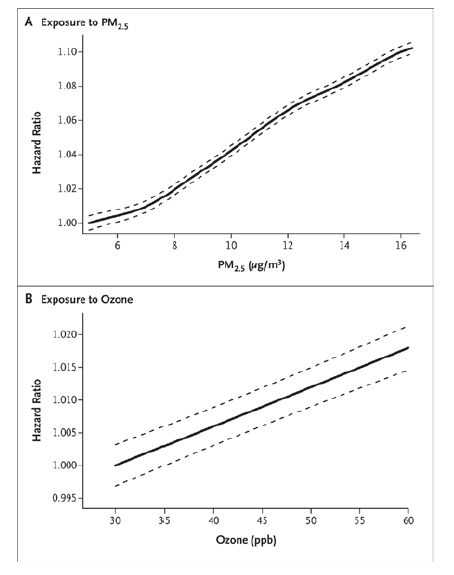

Growing particulate matter problems are having a profound effect on health in the U.S. and worldwide with grossly inadequate solutions.

Dangerous Combusted Products

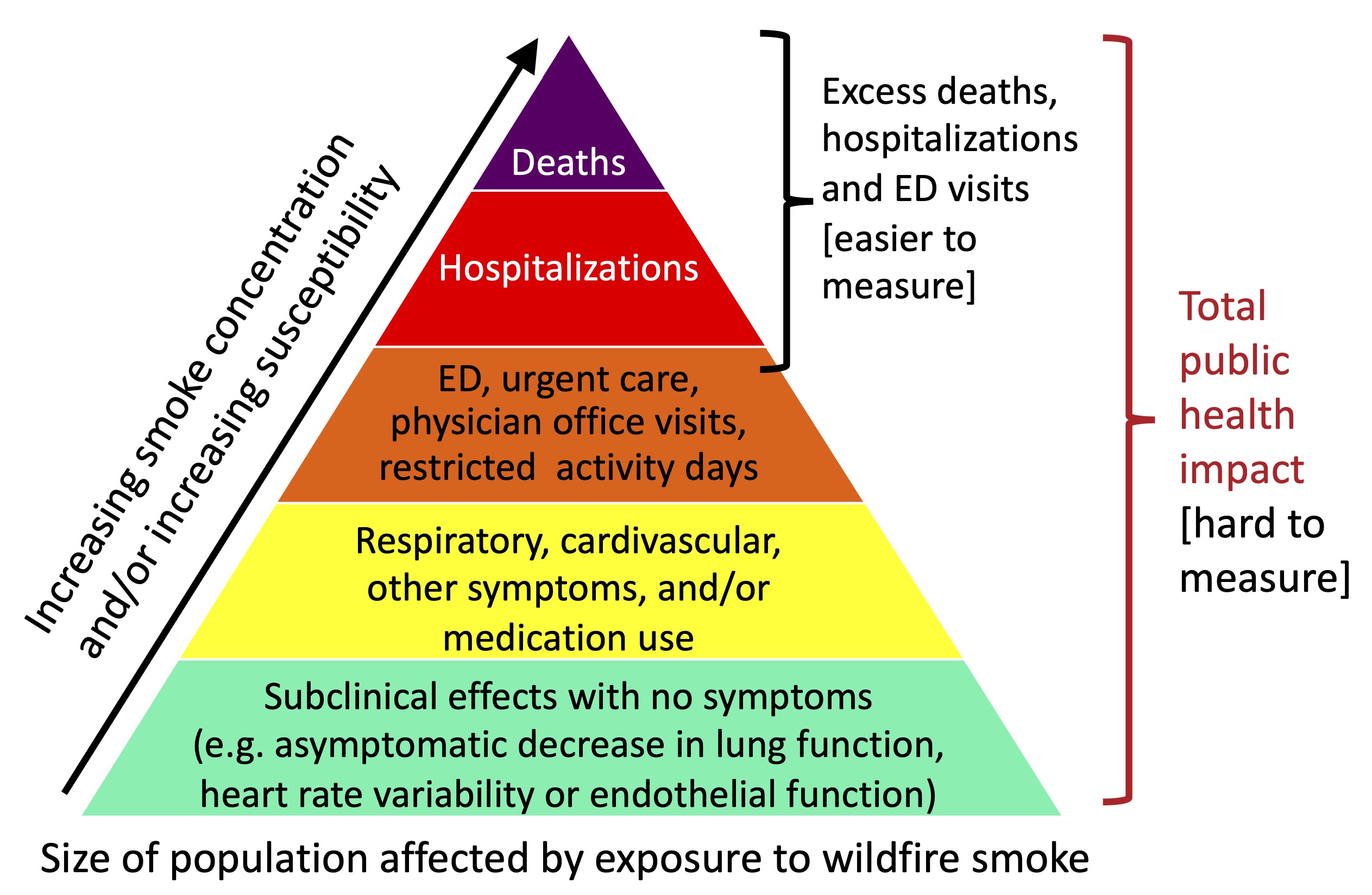

Wildfires: A Significant Cause of Mortality

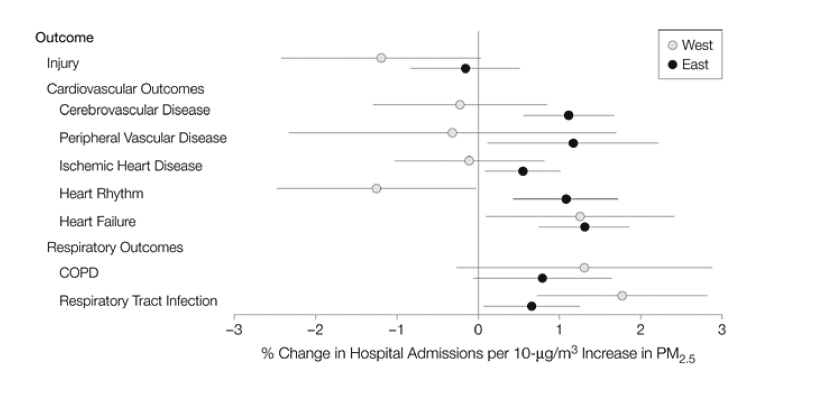

Percentage change in hospitalization rate by cause per 10 ug/m3 increase in PM2.5 for the U.S. Eastern and Western regions for all outcomes.

Source: Dominici, F. et al. JAMA 2006; 295:1127–1134.

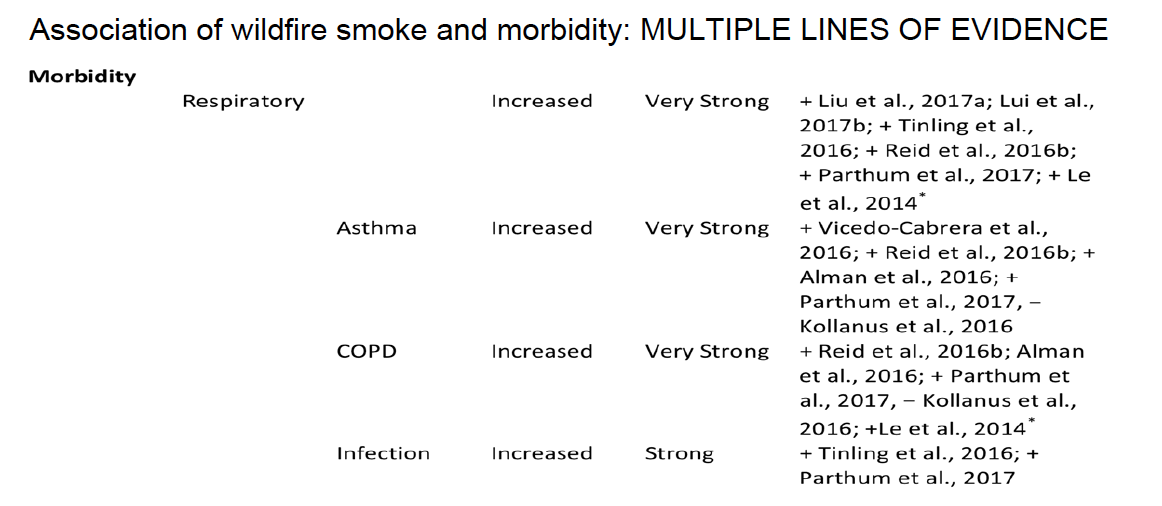

There is ample evidence associated with wildfire smoke and adverse health outcomes. The science in this area would ordinarily lead to regulations.

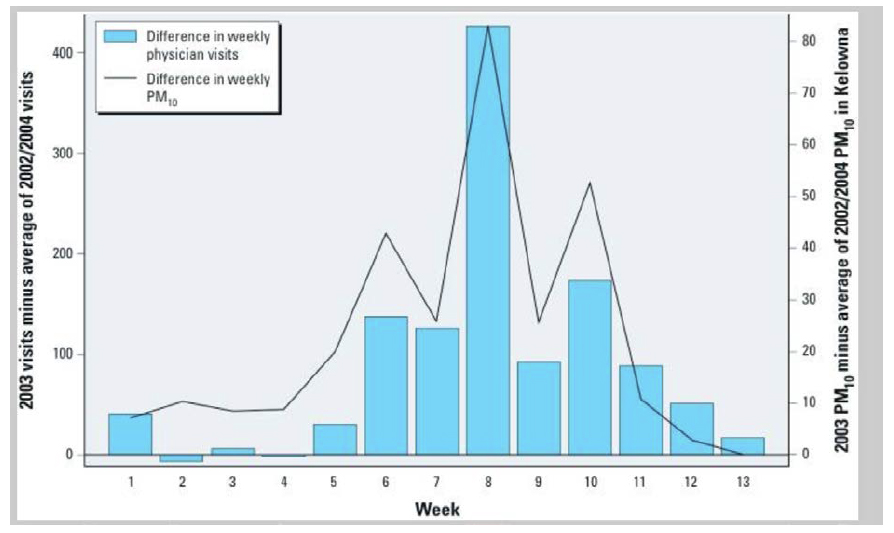

Kelowna, Australia: Impact of 2003 Bush Fires on PM10 and Weekly MD Visits

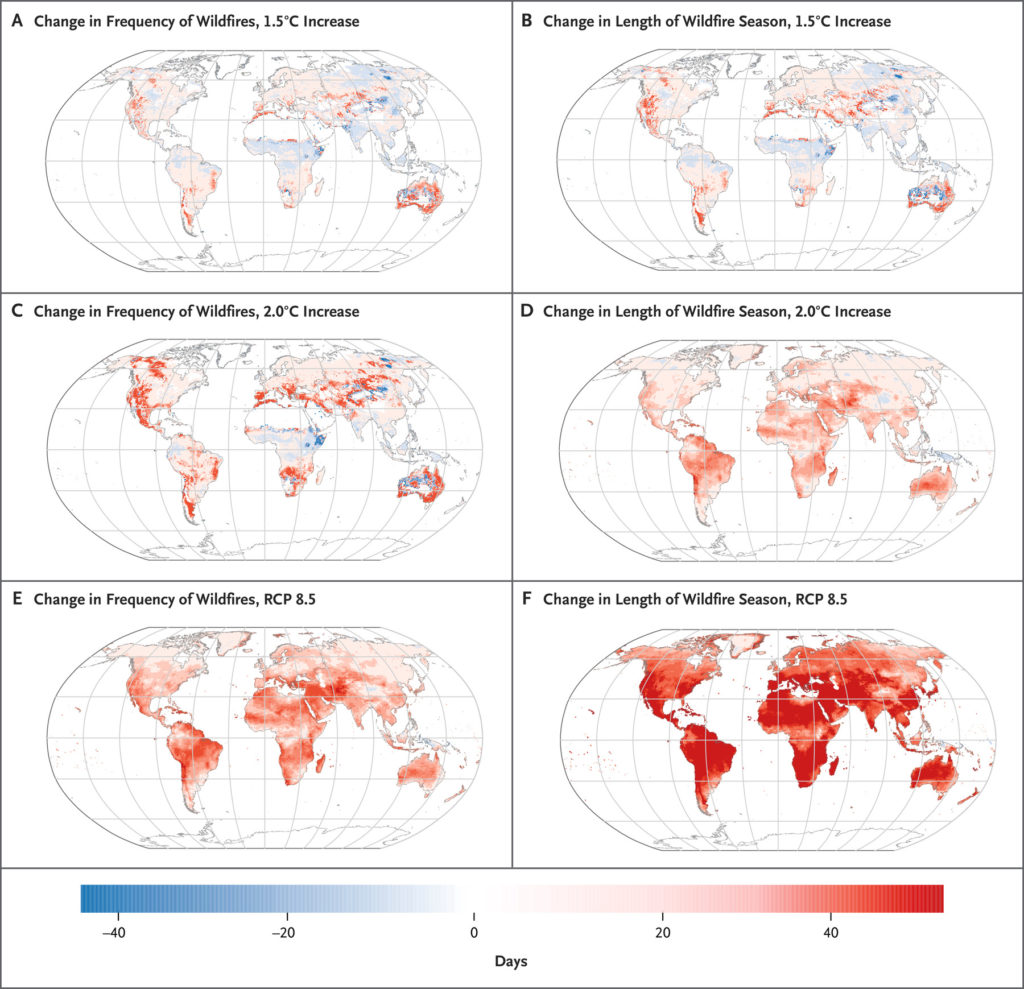

Projected Changes from 1981–2000 to 2080–2099

The above maps show the projected change from 1981–2000 to 2080–2099 in the frequency of wildfires (days with wildfire events per year) and the length of the wildfire season (days with a normalized daily fire danger index value above a threshold of 50 per year) with an increase in the global mean surface temperature of 1.5°C (Panels A and B) and with an increase of 2.0°C (Panels C and D) relative to the preindustrial level. Also shown is the projected change under the conditions of representative concentration pathway (RCP) 8.5 (Panels E and F), which is a future scenario of high greenhouse-gas emissions and no climate change–mitigation policy, with an increase in the global mean surface temperature of 3.2°C to 5.4°C relative to the preindustrial level (corresponding to an increase of 2.2°C to 4.4°C relative to the 2019 level).

- Frequency of wildfires

- Length of wildfire season

- Global mean surface-temperature increase.

Source: R Xu et al. Wildfires, Global Climate Change, and Human Health. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2173–2181.

Challenges with Degraded Air Quality

We face many challenges in managing climate change driven degraded air quality and risks to individuals and public health.

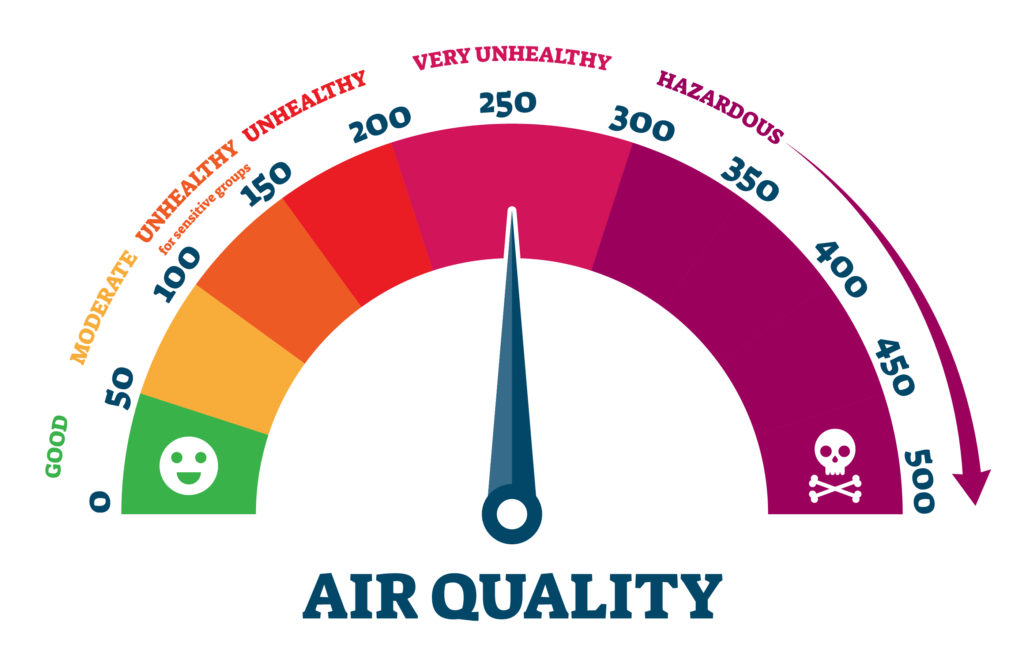

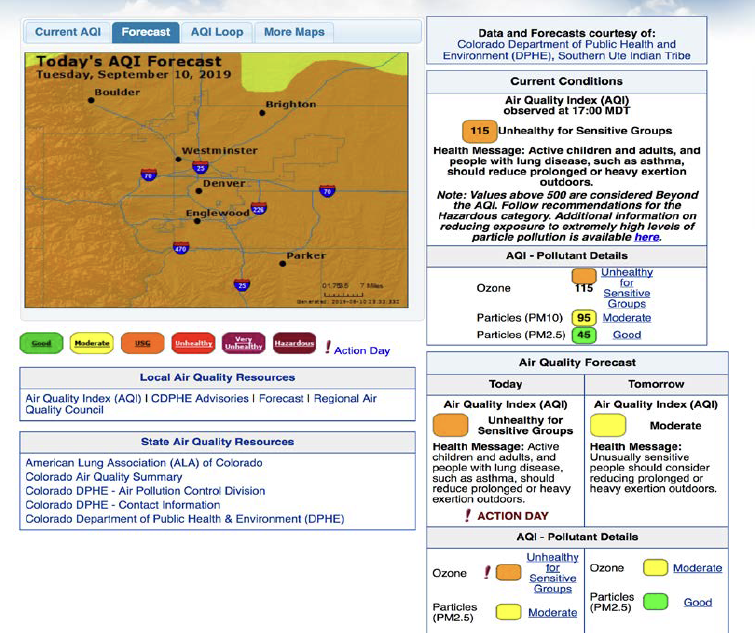

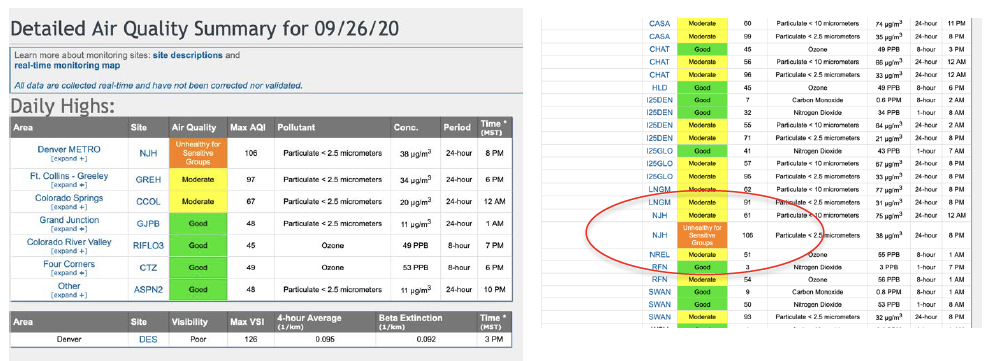

AQI (Air-quality index) forecasts lack granularity to be useful. There needs to be a consistent and coordinated effort to produce reliable data for the forecasts. AQI is calculated based on major air pollutants regulated by the Clean Air Act and include:

- Ground-level ozone

- Particle pollution

- Carbon monoxide

- Sulfur dioxide

- Nitrogen dioxide

What we see and how we are warned is inadequate.

Current Health Warnings for Smoke

Public health recommendations for areas affected by smoke:

If smoke is thick or becomes thick in your neighborhood you may want to remain indoors. This is especially true for those with heart disease, respiratory illnesses, the very young, and the elderly. Consider limiting outdoor activity when moderate to heavy smoke is present. Consider relocating temporarily if smoke is present indoors and is making you ill. IF VISIBILITY IS LESS THAN 5 MILES IN SMOKE IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD, SMOKE HAS REACHED LEVELS THAT ARE UNHEALTHY.

We don’t know what the long-term effects of wildfire pollution will be. It could mean long-term damage to the lungs, especially in children.

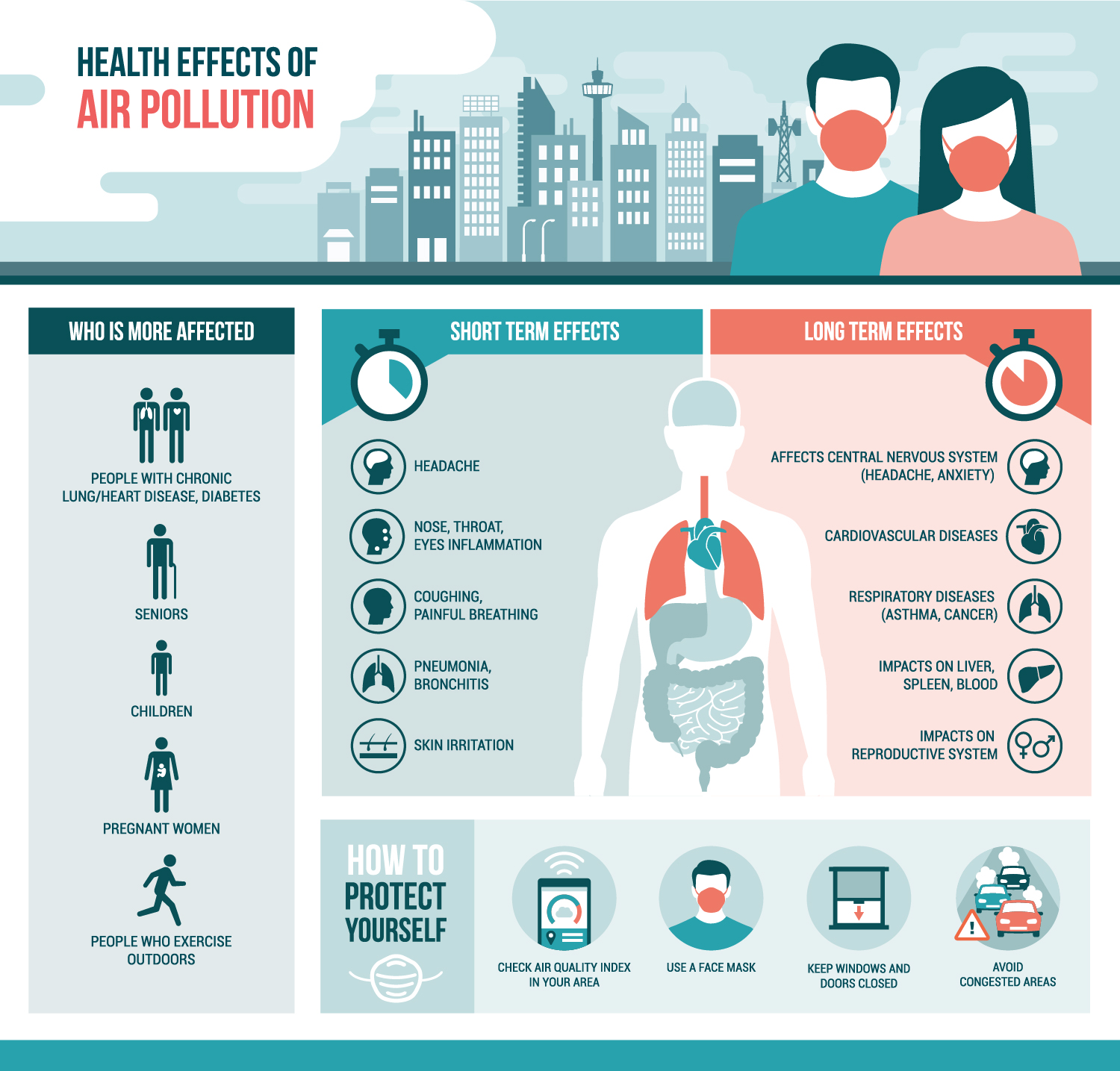

Impacts on Health and Activity

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution can impact almost every organ in the body. Small air pollutants can penetrate into the bloodstream via the lungs and circulate throughout the body and create systemic inflammation and carcinogenicity.

What Do You Tell Your Patients?

A 15-year-old male with asthma and a body mass index of 28.

- Family and primary care providers encourage more physical activity.

- In the summer of 2020, the patient needed a rescue inhaler 4 times during a moderate wildfire AQI event after walking family dog.

- Should the patient always avoid exercise or the outdoors when AQI is unhealthy?

- How does he know the AQI in real time where he lives?

- Preventive use of inhalers reduce his symptoms, so is it okay for him to exercise after using albuterol?

A 66-year-old man has chronic obstructive lung disease.

- Exercise is known to improve COPD outcomes, so the patient was encouraged by his MD to exercise daily.

- Due to wildfires in the West, PM levels were in the unsafe range, and predicted to stay that way for a week.

- Should the patient be told to stay inside and not go for walks?

- What other exercise regime might be possible?

An 8-year-old female loves playing on her soccer team but has a history of intermittent asthma symptoms after upper respiratory tract infections treated with sporadic albuterol.

- Should she skip soccer practice?

- What if a poor AQI event lasts for 4 weeks?

- During poor AQI events, could exercise cause her asthma to get worse in the long-term?

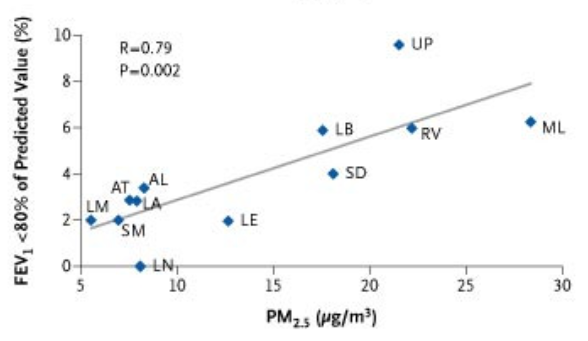

The Effect of Air Pollution on Lung Development from 10 to 18 Years of Age

Community-specific proportion of 18-year-olds with a FEV1 below 80 percent of the predicted value plotted against the average levels of pollutants from 1994 through 2000.

Public Health Goals

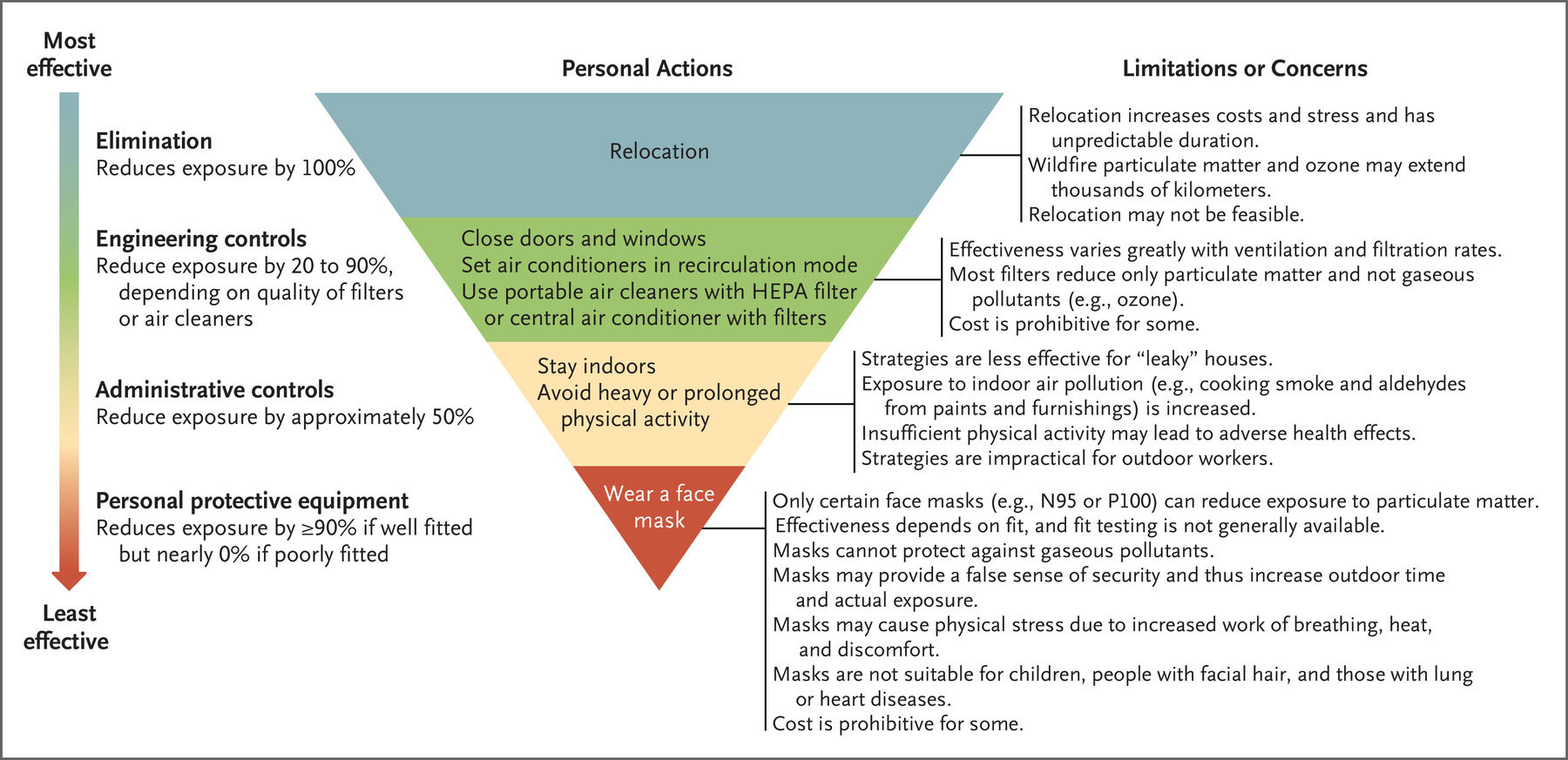

Take Action to Reduce Exposure to Wildfire Smoke and Its Health Risks

Current Best Recommendations

Educate parents and families about potential risks.

Know that children, adolescents, the elderly, and those with lung disease are more susceptible to the effects of air pollution than healthy adults.

Consider that individual sensitivity to pollution should be your primary guide for activity recommendations (outside of known very high-risk groups):

- What is the history of symptom flares requiring step-up in therapy?

- Should recess be held inside for fairness?

- Should an individual miss practices?

Recognize that there is no clear data to support blanket activity limitations during short-term moderately poor AQI events. Acknowledge that prolonged and recurrent wildfire-driven AQI events are an increasing concern that require more research to enable evidence-based recommendations.

Conclusion

As a public health goal, we must develop personalized and granular health and activity recommendations for degraded air quality.

References

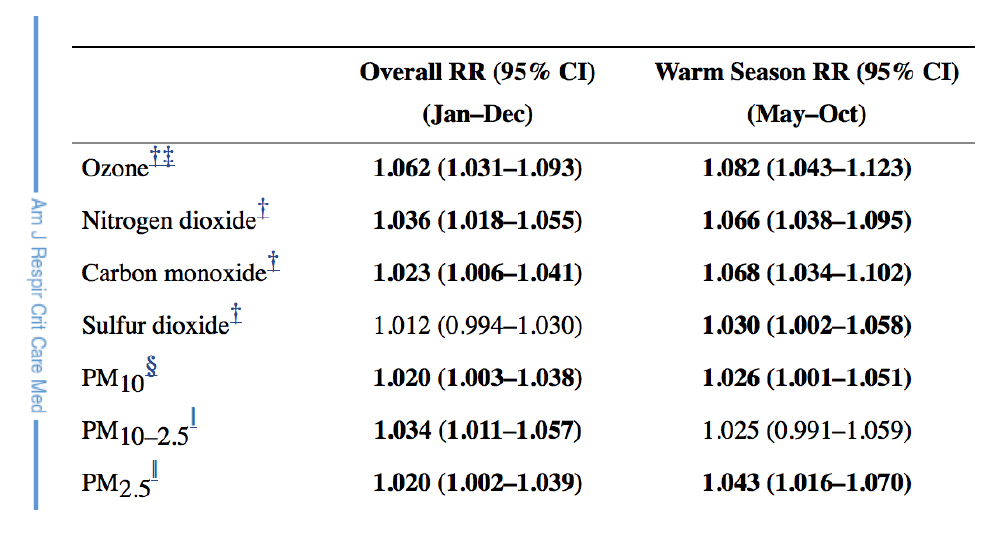

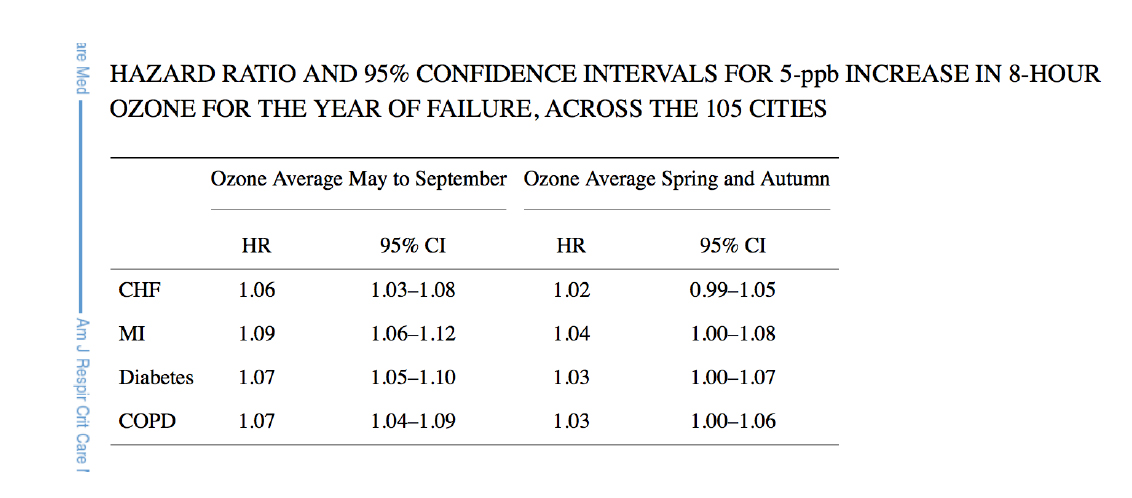

- Zanbetti et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Oct 1, 2011; 184(7): 836–841.

- Henderson et al, Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Sep; 119(9): 1266–1271.

- Akinbami et al, Environ Res. 2010 Apr;110(3):294–301.

- Dominici, F. et al. JAMA 2006;295:1127–1134.

- Reid CE, Maestas MM. Wildfire smoke exposure under climate change: impact on respiratory health of affected communities. CurrOpinPulmMed. 2019;25(2):179-187. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000552.

- Abatzoglou JT, Williams AP. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(42):11770-11775. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607171113.

- Xu R, Yu P, Abramson MJ, Johnston FH, Samet JM, Bell ML, Haines A, Ebi KL, Li S, Guo Y. Wildfires, Global Climate Change, and Human Health. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 26;383(22):2173-2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2028985. Epub 2020 Oct 9. PMID: 33034960.

- Reinmuth-Selzle K, Kampf CJ, Lucas K, et al. Air Pollution and Climate Change Effects on Allergies in the Anthropocene: Abundance, Interaction, and Modification of Allergens and Adjuvants. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(8):4119-4141. doi:10.1021/acs.est.6b04908.

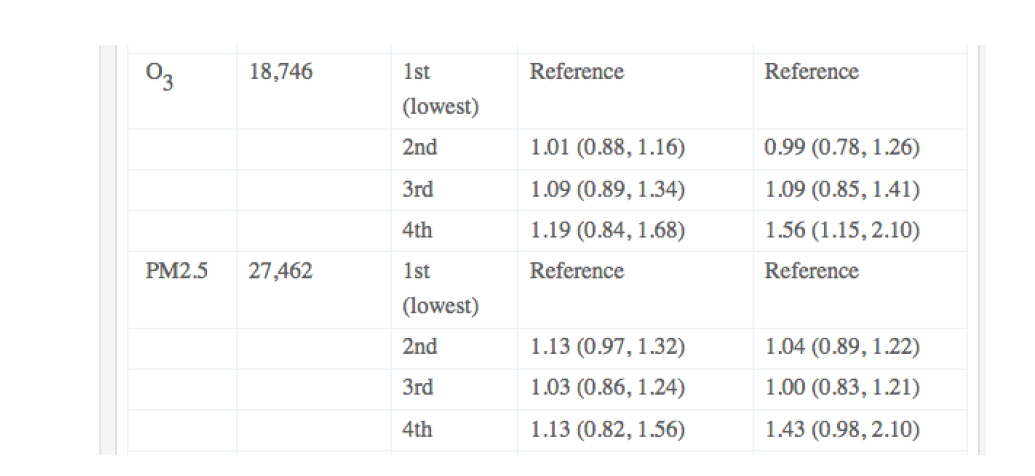

- Di Q, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, et al. Air Pollution and Mortality in the Medicare Population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2513-2522. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1702747.

- U.S. EPA. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for ozone and related photochemical oxidants (Final Report, Apr 2020). Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2020.

- Crooks JL, Licker R, Hollis AL, Ekwurzel B. The ozone climate penalty, NAAQS attainment, and health equity along the Colorado Front Range. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021 Sep 10. doi: 10.1038/s41370-021-00375-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34504294.

- Cascio, Wild fire smoke and human health. Sci Total Environ. 2018 May 15; 624: 586–595.

- Stowell JD, Kim YM, Gao Y, Fu JS, Chang HH, Liu Y. The impact of climate change and emissions control on future ozone levels: Implications for human health. Environ Int. 2017 Nov;108: 41-50. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.001. Epub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 28800413; PMCID: PMC8166453.

- Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. World Health Organization. 19 December 2022.

- The Inside Story: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.