Question 1

Which of the following best defines microaggressions?

Question 2

Exposure to microaggressions is associated with negative consequences including, but not limited to, mental health effects, physical health problems, loss of trust in the healthcare system, and strained relationships.

True

Correct

False

Incorrect

Try again

Question 3

Which of the following best describes the definition of the microaggression recipient?

Question 4

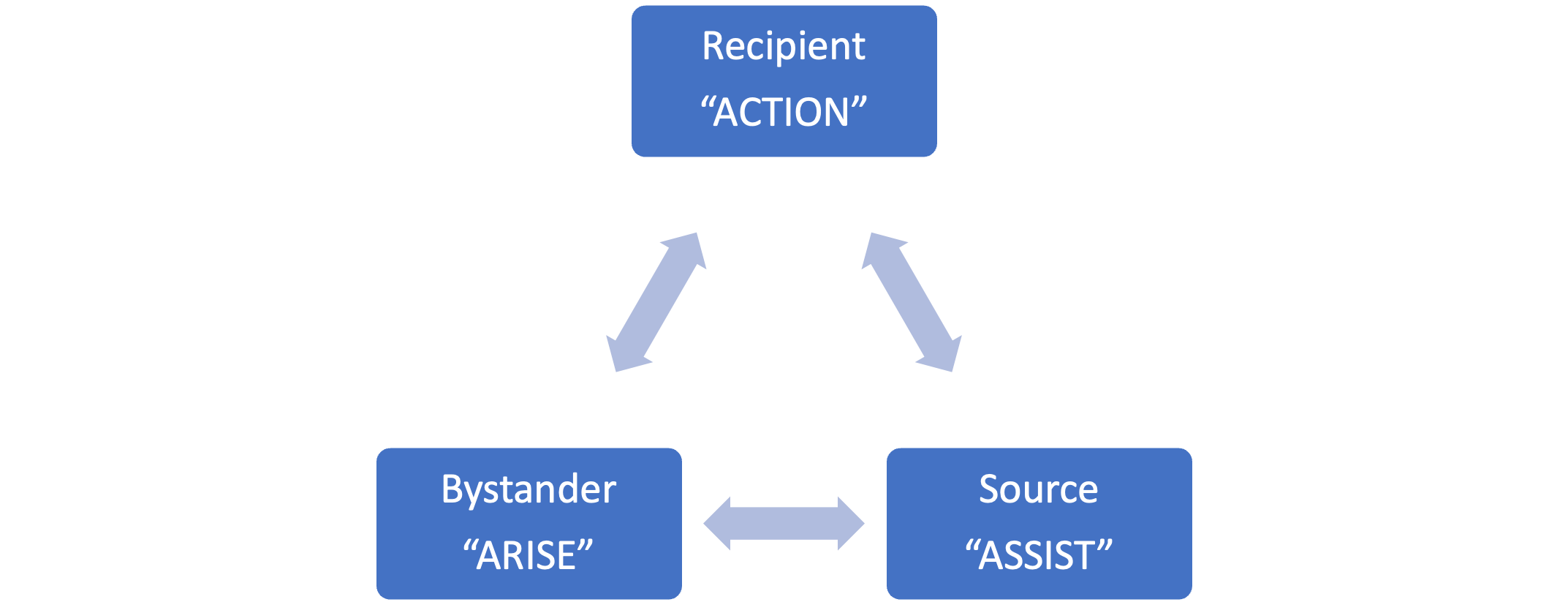

Use the Microaggressions Triangle Model to match the microaggression role to the most appropriate model for response.

You have now completed the Work Incivility module. You will have an opportunity to practice responding to microaggressions in your upcoming interprofessional education session.

- references

- Ackerman-Barger K, Jacobs NN, Orozco R, London M. Addressing microaggressions in academic health: a workshop for inclusive excellence. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11103.

- Ackerman-Barger, Kupiri PhD, RN; Jacobs, Negar Nicole PhD. The Microaggressions Triangle Model: A Humanistic Approach to Navigating Microaggressions in Health Professions Schools. Academic Medicine. 95(12S):p S28-S32, December 2020. | DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003692

- Anderson, N., Lett, E., Asabor, E.N. et al. The Association of Microaggressions with Depressive Symptoms and Institutional Satisfaction Among a National Cohort of Medical Students. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 298–307 (2022).

- Cheung F, Ganote CM, Souza TJ. Microaggressions and microresistance: Supporting and empowering students. In: Faculty Focus Special Report: Diversity and Inclusion in the College Classroom. 2016, Madison, WI: Magna Publication

- Sue DW. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. 2010, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bradberry, T., & Greaves, J. (2009). Emotional Intelligence 2.0. TalentSmart.