Those who have contributed least to climate change often suffer the most. This is a profound injustice we must address.

Climate change does not affect all populations equally. The mental health consequences are profoundly shaped by existing social, economic, and environmental inequities.

The climate justice framework

Understanding differential vulnerability

Mental health disparities emerge from multiple intersecting factors:

- Differential exposure: Marginalized communities face greater exposure to environmental hazards.

- Differential vulnerability: Pre-existing conditions, poverty, and systemic barriers increase susceptibility.

- Differential capacity to respond: Fewer resources for preparation, evacuation, and recovery.

- Differential access to care: Barriers to mental health services compound impacts.

Communities of color and low-income populations

Research on environmental justice documents that communities of color and low-income neighborhoods are disproportionately located in areas vulnerable to flooding, heat islands, and poor air quality. These communities face greater exposure to climate hazards while having fewer resources for preparation, evacuation, and recovery.

Hurricane Katrina: A case study in health inequity

Studies following Hurricane Katrina documented stark racial and economic disparities in mental health outcomes. African American survivors experienced higher rates of PTSD and depression, driven by factors including greater property damage, longer displacement, lower insurance coverage, and discrimination in aid distribution—illustrating how pre-existing inequities shape disaster mental health impacts.

Understanding through example

Consider two families living in the same city when a hurricane hits.

Family A has:

- Homeowners’ insurance.

- Savings.

- Family in another state.

- Flexible jobs that allow them to work remotely.

Family B has:

- Rents their home.

- Does not have renter’s insurance.

- Lives paycheck-to-paycheck.

- No car.

- Works an hourly job without sick leave.

Both families lose their homes to flooding from the hurricane. Their recovery trajectories—and their mental health outcomes—will be vastly different, not because the hurricane treated them differently, but because society’s structure created different levels of vulnerability.

Climate displacement and migration

The forced movement of people due to sudden or gradual environmental changes linked to climate change, including extreme weather events, sea level rise, drought, and environmental degradation.

An estimated 200 million people may become climate refugees by 2050. Refugees and migrants have specific physical and mental health needs linked to their exposure to climate and environmental conditions.

Research finds evidence of poorer mental health and wellbeing among migrants and displaced populations relative to populations of non-movers.

Key mental health impacts include:

- Loss of place and identity. Home provides:

- Security

- Identity.

- Community connection.

- Social network disruption.

- Fragments families.

- Removes crucial support systems.

- Legal and housing limbo. Uncertain status creates chronic stress and anxiety.

- Loss of livelihood. Losing not just homes but entire ways of life.

- Trauma exposure.

- Violence.

- Exploitation.

- Dangerous journeys compound mental health risks.

Case Study: The Martinez family

The Martinez family are small-scale coffee farmers from rural Guatemala. They have faced three consecutive years of crop failure due to changing climate patterns (irregular rainfall, higher temperatures affecting coffee plants). As a result, the family relocates to Guatemala City in search of economic stability.

Mr. Martinez presents with persistent sleep disturbance, loss of motivation, irritability, and withdrawal from social activities. Screening identifies major depression. He expresses deep grief over losing their land, fear that their cultural identity is eroding, and uncertainty about how to provide stability for their children in an unfamiliar urban environment.

- The primary driver is environmental change, rather than conflict or political instability (although these can co-occur).

- It tends to be more internal within a country’s borders.

- The displacement may be temporary or permanent depending on the nature of the environmental change.

- Loss of livelihood and social networks.

- Legal precarity.

- Discrimination.

- Limited access to care.

- Language barriers in urban settings.

- Loss of traditional knowledge and practices that provided meaning.

For more information

Climate Migration 101: An Explainer. Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

Indigenous communities

The concept of ecological grief is a form of emotional distress arising from observations of environmental degradation, including biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and the disappearance of familiar landscapes. For indigenous peoples, these losses can be particularly devastating.

Research documents significant mental health impacts in Indigenous communities experiencing environmental change. Studies show:

- Threats to traditional subsistence activities.

- Cultural transmission.

- Community cohesion, with documented increases in depression, anxiety, and distress.

Arctic communities example

In Arctic communities, research has documented how environmental changes threaten traditional practices tied to sea ice. The ice is not just a resource; it’s woven into cultural identity, stories, and ways of understanding the world. Its loss represents not just a practical challenge but a profound cultural and spiritual grief—a form of solastalgia that threatens the transmission of traditional knowledge to younger generations.

In Arctic communities, research has documented how environmental changes threaten traditional practices tied to sea ice. The ice is not just a resource; it’s woven into cultural identity, stories, and ways of understanding the world. Its loss represents not just a practical challenge but a profound cultural and spiritual grief—a form of solastalgia that threatens the transmission of traditional knowledge to younger generations.

Additional vulnerable groups

Workers whose livelihoods depend on stable climate conditions face unique mental health vulnerabilities. Like what? Some examples would be helpful.

- Crop failures and economic losses from drought, flooding, or temperature extremes.

- Uncertainty about future viability of farming practices.

- Witnessing environmental changes to land they work intimately.

Recent research documents that 60% of United States farmers identify drought as their top weather-related concern. Drought is linked to:

- Mental distress.

- Reduced life satisfaction.

- Increased suicidality among farmers who already face elevated baseline depression rates.

Contend with:

- Repeated exposure to traumatic events.

- Burning homes.

- Injured civilians.

- Environmental destruction.

- Approximately 20% meet criteria for PTSD during their careers (versus 6.8% in the general population), and up to 30% develop behavioral health challenges including depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

- Extended separation from families during increasingly long disaster seasons

Moral distress from witnessing suffering they cannot prevent.

Immigrant groups, particularly those with limited English proficiency and undocumented status, face compounded mental health vulnerabilities during climate events:

- Fear of seeking help due to immigration status concerns.

- Language barriers limiting access to warnings and services.

- Social isolation from extended family support networks.

- Economic precarity, often in climate-vulnerable occupations.

- Ineligibility for disaster assistance programs.

- Experience of discrimination that compounds disaster-related stress.

Rural populations face distinct mental health challenges:

- Limited access to mental health services.

- Mental health provider shortages.

- Economic dependence on climate-sensitive sectors (agriculture, forestry, fishing).

- Geographic isolation increasing response times during emergencies.

- Greater stigma around mental health in some rural communities.

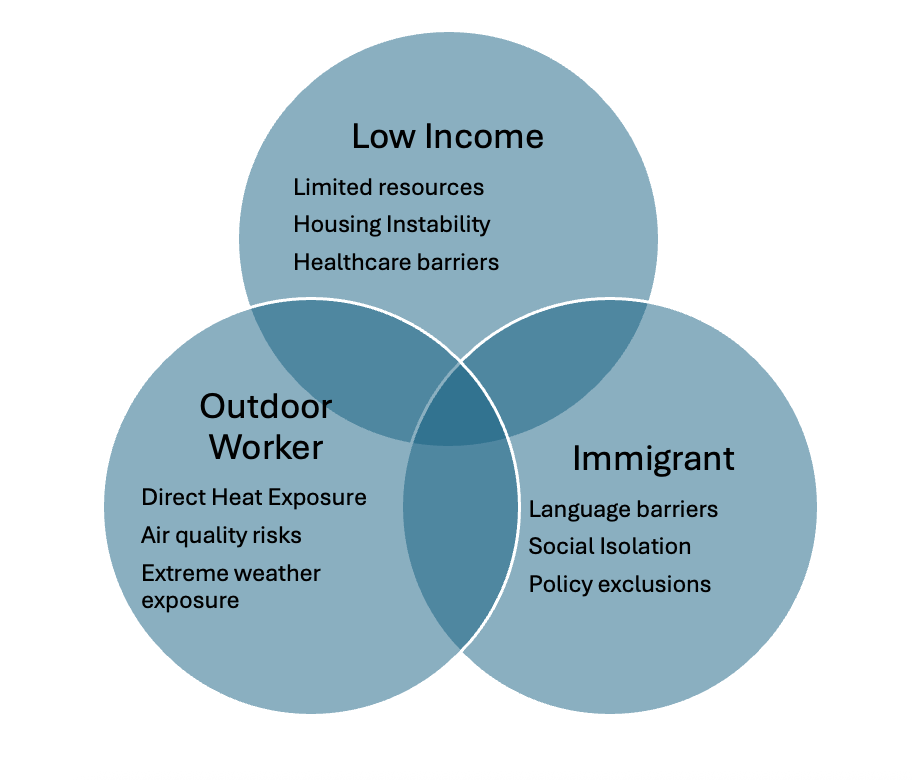

Many individuals belong to multiple vulnerable groups simultaneously, facing compounded risks.

For example, an undocumented farmworker faces:

- Occupational heat and economic stress from crop failures.

- Immigration status fears preventing help-seeking.

- Language barriers.

- Economic precarity.

- Limited healthcare access.

Understanding these intersections is essential for providing trauma-informed, equity-centered care.

Intersecting vulnerabilities

Intersecting vulnerabilities

- When someone is both low income AND an outdoor worker, they cannot afford to miss work during dangerous weather conditions.

- Outdoor workers who are also immigrants frequently lack workplace protections and advocacy.

- Low-income immigrants face barriers to disaster recovery aid.

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.

previous

Mental Health Consequences

of Climate Change

Next

Surveillance and Monitoring