G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest group of membrane receptors. They are cell surface receptors that play a role in an array of functions in the human body. GPCRs play a large role in human physiology and pharmacology.

What percentage of medications act by binding GPCRs?

10%

INCORRECT

Try again

25%

INCORRECT

Try again

50%

CORRECT!

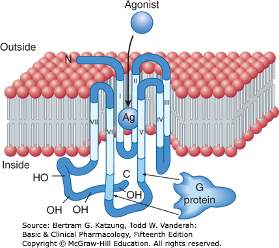

Structure of GPCRs

GPCRs consist of a single polypeptide that is folded into a globular shape and embedded in a cell’s plasma membrane. The polypeptide has seven segments and spans the entire width of the membrane, hence the name, seven-transmembrane receptor. The intervening portions loop both inside and outside the cell.

Function of GPCRs

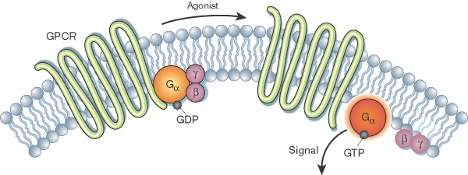

As their name suggests, GPCRs interact with G proteins in the plasma membrane. When an external signaling molecule binds to a GPCR, it causes a conformational change in the GPCR. The conformational change triggers an interaction between the GPCR and a nearby G protein.

G proteins are specialized proteins with the ability to bind the nucleotides guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and guanosine diphosphate (GDP). The G proteins that associate with GPCRs are heterotrimeric, meaning they have three different subunits: an alpha subunit, a beta subunit, and a gamma subunit. Two of these subunits—alpha and gamma—are attached to the plasma membrane by lipid anchors.

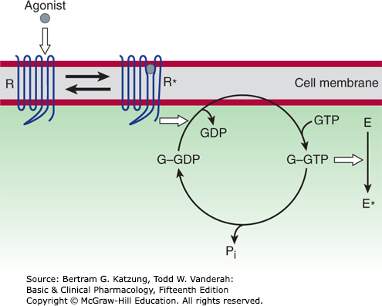

A G protein alpha subunit binds either GTP or GDP depending on whether the protein is active (GTP) or inactive (GDP). In the absence of a signal, GDP attaches to the alpha subunit, and the entire G protein-GDP complex binds to a nearby GPCR. This arrangement persists until a signaling molecule joins with the GPCR. At this point, a change in the conformation of the GPCR activates the G protein, and GTP physically replaces the GDP bound to the alpha subunit. As a result, the G protein subunits dissociate into two parts: the GTP-bound alpha subunit and a beta-gamma dimer. Both parts remain anchored to the plasma membrane, but they are no longer bound to the GPCR, so they can now diffuse laterally to interact with other membrane proteins. G proteins remain active if their alpha subunits are joined with GTP. However, when this GTP is hydrolyzed back to GDP, the subunits once again assume the form of an inactive heterotrimer, and the entire G protein reassociates with the now-inactive GPCR. In this way, G proteins work like a switch—turned on or off by signal-receptor interactions on the cell’s surface.

Specific targets for activated G proteins include various enzymes that produce second messengers, as well as certain ion channels that allow ions to act as second messengers. Some G proteins stimulate the activity of these targets, whereas others are inhibitory.

Another way to think of GCPRs is by considering their relationship with agonists.

This figure depicts an agonist activating a GPCR. The agonist (drug/ligand) activates the receptor (R→R*), which promotes release of GDP from the G protein (G), allowing entry of GTP into the nucleotide binding site. In its GTP-bound state (G–GTP), the G protein regulates activity of an effector enzyme or ion channel (E→E*). The signal is terminated by hydrolysis of GTP, followed by the return of the system to the basal unstimulated state. Open arrows denote regulatory effects. (Pi, inorganic phosphate).

When considering the activation process of G protein coupled receptors, which subunit joins with GTP or GDP to result in stimulation or inhibition?

Alpha

CORRECT!

Beta

INCORRECT

Try again

Gamma

INCORRECT

Try again

GPCR Second Messengers

Activation of a single G protein can affect the production of hundreds or even thousands of second messenger molecules. Recall that second messengers—such as cyclic AMP (cAMP), diacylglycerol (DAG), and inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate (IP3)—are small molecules that initiate and coordinate intracellular signaling pathways.

GPCRs are a large family of cell surface receptors that respond to a variety of external signals. Binding of a signaling molecule to a GPCR results in G protein activation, which in turn triggers the production of any number of second messengers. Through this sequence of events, GPCRs help regulate an incredible range of bodily functions, from sensation to growth to hormone responses.

One especially common target of activated G proteins is adenylyl cyclase, a membrane-associated enzyme that, when activated by the GTP-bound alpha subunit, catalyzes synthesis of the second messenger cAMP from molecules of ATP. In humans, cAMP is involved in responses to sensory input, hormones, and nerve transmission, among others.

Phospholipase C is another common target of activated G proteins. This membrane-associated enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of not one, but two second messengers—DAG and IP3—from the membrane lipid phosphatidyl inositol. This particular pathway is critical to a wide variety of human bodily processes. For instance, thrombin receptors in platelets use this pathway to promote blood clotting.

Different G protein classes impact secondary messengers in different ways.

- Gs proteins: Stimulate adenylyl cyclase.

- Gi proteins: Inhibit adenylyl cyclase.

- Gq proteins: Stimulate phospholipase c.

Now, we will apply GPCR information to the Autonomic Nervous System.