Case adapted from

Lier AJ, Tuan JJ, Davis MW, Paulson N, McManus D, Campbell S, Peaper DR, Topal JE. Case Report: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis in a Patient with Covid-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 Oct;103(4):1590-1592. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0699.

He has a history of DM complicated by neuropathy, hypertension, and COPD. He quit smoking 4 years ago after a 30 pack-year history. He grew up in Ecuador but now resides in eastern Washington. He is retired from work in the timber industry in northern Idaho.

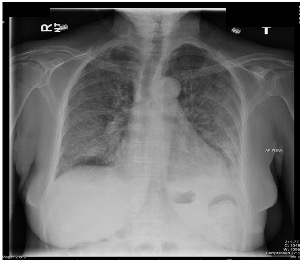

He was admitted for treatment of severe COVID and started on Methylprednisolone and Tocilizumab (anti-IL6-receptor antibody).

Questions for consideration

- What is the most likely pathogen? And what is the name of the syndrome that this patient had?

- What, if any, relationship does this syndrome have to the organisms found in the blood culture?

- Where did this patient acquire the infection?

- What other diagnostic tests should be done to investigate risk factors for this syndrome?

- Why is there eosinophilia? Which other organisms cause eosinophilia, and what do they have in common with this one?

- What is the treatment for this condition?

Watch

Strongyloides stercoralis

- Epidemiology

- Life Cycle

- Clinical

- Clinical—Late Infection

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Prevention

- Key concepts

Tropics, esp. children, where autoinfection is common.

- Nematodes (roundworms) hookworm-like adults, fecal-soil-skin transmission, plus lung migration and autoinfection

- Closely related to Hookworm.

- Skin penetration (not oral), with lung phase.

- Parasite does not need to exit the body to complete life cycle—autoinfection.

- Skin migration: Rash is common (“larva currens”).

- Lung migration: Similar to Ascaris and hookworm.

- GI upset: Abdominal pain or diarrhea.

- May persist for years or decades via autoinfection.

- Rash.

- “Larva currens” on exam.

- Eosinophilia common (but not always).

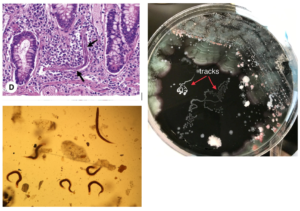

- Look for larvae in stool (<50% sensitive), sputum culture (“tracks”), or tissue.

- Serology (ELISA IgG) if immunocompetent.

Ivermectin (treat before immunosuppression).

- Improved sanitation.

- Wear shoes.

AKA: “Strongy.”

Micro:

- Nematodes (roundworms) hookworm-like adults.

- Fecal-soil-skin transmission.

- Lung migration and autoinfection.

Epidemiology: Tropics, (esp. children), autoinfection common.

Clinical:

- Larva Currens.

- Loeffler’s.

- GI upset.

- Hyperinfection.

Diagnosis:

- Rash.

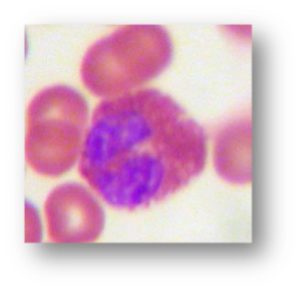

- Eosinophilia.

- Sputum or CSF for larvae.

Therapy: Ivermectin (treat before immunosuppression).

Prevention: Preemptive Rx. Improved sanitation, wear shoes.

Test your knowledge

Strongyloides sterocalis. Hyperinfection syndrome.

Strongyloides is unique in that the mature adult worm in GI tract can produce eggs that develop into the infectious stage (rhabitiform larvae) all within the host GI lumen. The rhabitiform larvae then penetrate the colonic wall to access the blood stream. When many larvae are doing this, chances increase that bacteria from the colon can translocate to the bloodstream as well.

Most likely, this patient’s primary infection was years earlier in Ecuador, where the organism is endemic in the environment.

Hyperinfection is more common in the setting of immunosuppression; in this case, the glucocorticoids and IL-6 inhibition were contributing factors. All patients with severe Strongyloidiasis should also be screened for HIV and HTLV-1—both of these retroviruses impair specific cell-mediated immunity pathways essential in immune response to Strongyloides response.

- Eosinophils play a key role in response to parasitic infections within tissues or blood—in particular, helminths are among the strongest stimulants for eosinophilia (i.e., protozoa characteristically do not elicit much eosinophilic response). The magnitude of eosinophilic response directly correlates with the degree of tissue invasion and/or migration through tissue of the parasite. Correspondingly, eosinophilia is most associated with the helminths that have invasive and migratory phases—Strongyloides, acute Hookworm (Ancylostoma and Necator), and acute Ascaris. For helminths that remain in the GI lumen or well-contained in tissues:

- Tapeworms.

- Adult ascaris.

- Echinococcal cysts: Eosinophilia is usually absent.

- Eosinophils are also exquisitely sensitive to steroids, which can interfere with diagnostic suspicion in Strongyloides hyperinfection, where steroids may be the inciting cause. In the setting of concurrent steroids, any amount of eosinophilia should be considered relevant.

The treatment of choice for Strongyloidiasis is Ivermectin.