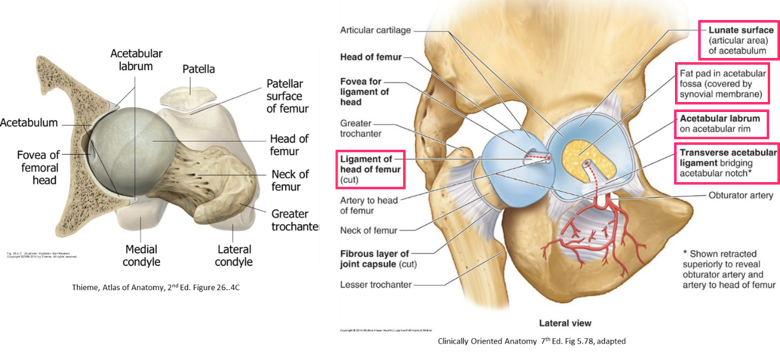

Figure 23.1

- The hip joint is the articulation between the round femoral head and the concave acetabulum (“little vinegar cup”).

- The lunate surface is the articular surface of the acetabulum, forming an arc that fills ¾ of the acetabular cup. It is covered with articular cartilage.

- The acetabulum is deepened by the acetabular labrum, a rim of fibrocartilage that encircles the entire edge of the acetabulum. This adds depth and stability to the hip joint.

- The hip joint is a multiaxial ball and socket synovial joint that is the second most movable joint in the body.

- Very strong since its primary function is to support the body weight.

Hip joint capsule

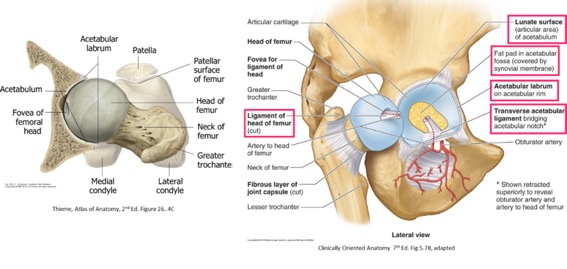

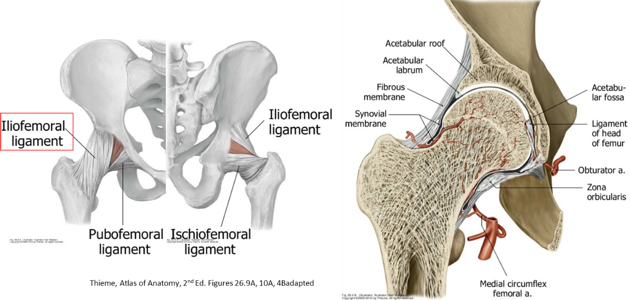

Figure 23.2

- Formed by an external fibrous layer and an internal lining, the synovial membrane

- Proximally the capsule attaches to the acetabulum of the hip bone just on the outside of the acetabular labrum.

- Distally, the fibrous layer of the capsule attaches anteriorly to the greater trochanter and intertrochanteric line. Interestingly, it has no attachment to the posterior side of the femur but is reinforced by ligaments there.

- The fibrous layer of the hip joint capsule has thickened regions that form three capsular ligaments: the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments. These ligaments pass from the hip bone to the femur in a spiral fashion, inserting on the greater trochanter and intertrochanteric line on the anterior side of the proximal femur.

Robust, “Y”-shaped ligament that runs vertically downward from the ilium and fans-out to the intertrochanteric line on the proximal femur. Considered to be one of the strongest ligaments in the body.

-

- Specifically prevents hyperextension of the hip during standing by screwing the femoral head into the acetabulum.

Reinforces the posterior side of the hip joint, it runs from the ischium to the greater trochanter. Weakest of the three hip joint ligaments. This, along with the lack of attachment of the fibrous joint capsule to the posterior femur, are reasons why most hip joint dislocations occur in a posterior direction.

Stretches from the pubic bone to the femur on the anterior side of the hip joint. It blends with the iliofemoral ligament and tightens during extension and abduction, preventing “hyper-abduction” of hip.

-

- Prevents hyper-abduction of the hip

Weak ligament that is often composed only of a band of synovial membrane. In the adult it offers little strength to the hip joint. It carries a small arterial branch of the obturator artery.

- As the femur is extended, the ligaments that spiral around the hip joint tighten, increasing joint congruency and intracapsular pressure.

- Intracapsular pressure in a healthy joint is just less than atmospheric pressure, creating suction that adds to the stability of the joint and prevents dislocation.

- Unlike the glenohumeral joint, the static elements that support the hip joint are vitally important to its stability. These include the deep socket of the acetabulum, which covers more than 50% of the femoral head and the robust capsular ligaments = the bony architecture and stout ligaments make the hip joint highly stable.

Clinical correlation: Traumatic hip dislocation

Hip dislocations usually occur in the posterior direction because the posterior part of the hip joint capsule is weakest, between the iliofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments. The head of the femur passes in this direction as the result of violent force, such as motor vehicle accidents when the flexed knee hits the automobile dashboard.

Clinical correlation: Congenital hip dislocation (hip dysplasia)

Dislocation of the hip is one of the most common congenital limb anomalies. It needs to be diagnosed in the first few days of life; otherwise it could produce serious lifelong consequences. The acetabulum doesn’t ossify until after birth. Normal development of the acetabulum in utero depends on the presence of the round femoral head within the acetabulum. A poor “fit” between the developing femoral head and developing acetabulum in utero can lead to underdevelopment, resulting in a shallow acetabulum that doesn’t sufficiently “cover” the femoral head.

If not corrected, hip dysplasia can lead to labrum tears and osteoarthritis. Hip dysplasia is more prevalent in certain racial groups, is five times more common in females, and runs in families. The positioning of the fetus in the uterus, such as breech positioning, seems to be a risk factor as is oligohydramnios (low amniotic fluid levels).

Newborn babies should always be checked for hip dysplasia, and it is usually evaluated during well-baby checkups.

Blood supply to the hip

Figure 23.3

- Medial circumflex femoral artery: Supplies the head and neck of the femur, and gives the most abundant arterial supply to the hip joint via intracapsular retinacular arteries.

- Lateral circumflex femoral artery: Gives fewer and smaller retinacular arteries.

- The artery to the head of the femur traverses the ligament of the head. Variable in size.

Clinical correlation: Hip fractures

Hip fractures are fractures of the proximal femur. They typically occur in two places:

-

- Femoral neck fractures—within the hip joint capsule,between the trochanters and the head of the femur

- Intertrochanteric fractures—outside the hip joint capsule, along the ridge between the greater and lesser trochanters.

Hip fractures in younger adults are due to high energy trauma—for example, skiing, falls from high places, or car accidents. The majority of hip fractures, however, occur in adults over age 60, especially those with osteoporosis.

Femoral neck fractures are especially serious, because they can damage the retinacular arteries that supply the head of the femur. Retinacular arteries are branches of the circumflex femoral arteries (mainly the medial circumflex femoral artery) that course through the periosteum of the femoral neck to reach the femoral head. Retinacular arteries are the main source of blood to the femoral head (the other source is the artery of the ligament of the head—from the obturator artery—a small, unreliable blood vessel). Therefore, if the retinacular arteries are damaged by a femoral neck fracture, the femoral head is predisposed to avascular necrosis = bone death.

Innervation of the hip

The hip is innervated by branches of the femoral and obturator nerves. Hip pain often refers to dermatomes L-2, L-3, and L-4, in the groin region and medial thigh. Primary hip pain (originating from the hip joint) can be difficult to distinguish from pain from other regions (lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joints),since sensory nerve fibers from these regions enter the same spinal cord segments as do fibers from the hip joint.

Hip joint movements

Table 23.1 Prime movers of the hip joint

|

Movement at the Hip |

Main muscles producing the movement (other muscles may assist) |

|

Flexion |

Iliopsoas is the strongest |

|

Extension |

Gluteus maximus, Hamstrings |

|

Abduction |

Gluteus medius and minimus, Tensor fasciae latae |

|

Adduction |

Adductor muscles, Pectineus, Gracilis |

|

External rotation

|

Obturator muscles, Piriformis, Gemelli, Quadratus femoris, Gluteus maximus |

|

Internal rotation |

Gluteus medius and minimus |

- Tying it all together with Acland

- Additional detailed videos