Anatomy is the study of the structure of the human body, from the molecular to the macroscopic, and includes the examination of development and functional significance. It is the structural setting in which function occurs.

Philosophy of teaching and learning anatomy

Anatomy is much more than knowing “the hip bone is connected to the thigh bone.” It is a challenge to master the volume of new terms and concepts. Organizing the material and making sense of it, rather than simply memorizing lists of facts, requires planning and discipline—this challenge is exciting and it builds confidence.

Non-anatomical cognitive skills will be emphasized as much as the topographic material itself. Anatomy is a perfect subject for practicing organization, visualization, description, and clear, concise communication with your colleagues. These skills will come in handy in other courses and in your medical careers.

In the lab, students should expect that they will learn more than just terminology and facts. Lab sessions emphasize teamwork, exploration, discovery, and integration with other areas such as development, pathology, and medical imaging. For students, it may be their first encounter with death and the deceased, proof of aging and disease, and possibly recognition of their own mortality. No prior life experience will likely have prepared students for the lab encounter. Confronting and dealing with the emotional challenges presented by gross anatomy contributes to professional development.

Study tips

-

Anatomy is a visual science.

The best way to learn it is to be able to recall it visually and be able to describe it based on what you see in your “mind’s eye.”

-

Spend time talking about anatomy with classmates.

Form a study group. Getting in the habit of having these anatomy “rap sessions” is worth the effort.

-

Scan the assigned reading in your texts and look over the related figures in your atlas before class.

Look up terms that are foreign to you in a medical dictionary. Having an idea of what will be discussed in large group sessions and dissected in lab will give you a foundation of knowledge to build on.

-

Keep a list of gaps in your knowledge and uncertainties.

If you are having trouble, make an appointment to see one of your instructors.

-

Sketch! Sketch! Sketch!

Do little sketches, flow-charts, or even stick-drawings.

Bring colored pencils or pens to class. Draw on the white boards in the small-group sessions and in lab. Involve other students in the sketching, making these get-togethers “chalk talks.” Sketching and talking about anatomy works!

Get in the habit of sketching outside of class too. This is preferable to memorizing facts from flashcards. Just tell any curious onlookers that you’re a medical student—they’ll understand.

The “four anatomies”

- Gross Anatomy

- Developmental anatomy

- Radiologic anatomy

- Living anatomy

No, this doesn’t imply that anatomy is a “yucky” subject. Gross anatomy is macroscopic anatomy, dealing with structures that are visible to the naked eye. Gross anatomy is traditionally studied by observation, palpation (feeling), and dissection of the cadaver—although much can be learned in this class from living bodies, too!

The study of growth and development of the human from a single cell (the zygote)into an adult. Embryology is a sub-discipline of developmental anatomy concerned with the study of embryos = the developing human during the first 8 weeks of gestation.

This is the study of body structure using imaging techniques (radiographs, CT, MRI, etc.). Radiologic anatomy is the anatomical basis of the field of radiology.

Since anatomy is truly the study of living human beings, the observation and palpation of the body is an important aspect of learning gross anatomy. Surface anatomy is another name for living anatomy—learning landmarks on the surface provides insight into the position of the underlying organs and structures. Living anatomy is the basis for the physical exam of the body.

Anatomic terms of position, direction, and relationship

The anatomic position (Figure 1.1) is used as the reference for all of the terms of description in gross anatomy. You will have to place yourself in this position or imagine yourself assuming this position in order to understand anatomic terminology.

It’s imperative that you gain a handle on the terms of relationship, terms describing movements, and anatomic planes used in anatomy fairly quickly (see Table 1.1, Table 1.2, and Table 1.3 for a list of terms). Anatomy is a descriptive science, so the accurate use of anatomic terms is important in order to avoid confusion and to communicate effectively with your colleagues and associates.

Table 1.1 Terms of relationship and comparison

|

Term |

Meaning |

|

Superior |

Situated above; Closer to the head. |

|

Cranial |

Closer to the head. Used properly with embryos. |

|

Inferior |

Situated below; Away from the head or closer to the foot. |

|

Caudal |

Closer to the coccyx or tailbone. Used properly with embryos. |

|

Anterior (Ventral) |

Closer to the front side (belly) of the body. Anterior and ventral can be used synonymously, but ventral is properly applied to embryos. |

|

Posterior (Dorsal) |

Closer to the back side of the body. Posterior and dorsal can be used synonymously, but dorsal is properly applied to embryos. |

|

Medial |

Closer to the midline of the body. |

|

Lateral |

Farther from the midline of the body. |

|

Proximal |

Closer to the origin or attachment of a structure. Limbs = toward their attachment to the trunk; vessels/nerves = toward their beginning or origin. |

|

Distal |

Farther from the origin or attachment of a structure. Limbs = farther from their attachment to the trunk; vessels/ nerves = farther from their beginning or origin. |

|

Superficial |

Closer to the surface of the body. |

|

Deep |

Farther from the surface of the body |

|

External |

Away from the center of a body cavity or lumen of a hollow organ – used when describing layers of the body wall or layers in the wall of a hollow organ. |

|

Internal |

Toward the center of a body cavity or lumen of a hollow organ – used when describing layers of the body wall or layers in the wall of a hollow organ. |

Table 1.2 Terms describing movements

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Flexion |

Bending in a direction that approximates the surfaces of adjacent body parts; Decreasing the angle between adjacent body parts. |

|

Extension |

Opposite of flexion. Straightening of adjacent body parts; Increasing the angle between adjacent body parts. What do you suppose hyperextension is? |

|

Abduction |

Moving a structure away from the midline of the body or a body part. Note the difference when using the term for (1) entire limbs, and (2) fingers and toes (digits). [Abducting someone is taking them away!] |

|

Adduction |

Moving a structure toward the midline of the body or a body part. |

|

Rotation |

Moving a structure around an axis; in the case of the limbs, it’s the long axis of the limb |

|

Elevation |

Moving a structure superiorly. Try this for your shoulders and lower jaw (mandible). |

|

Depression |

This isn’t feeling sad, it’s moving a structure toward the feet! The opposite of elevation. |

|

Protrusion |

Moving a structure anteriorly. Again, try this with your shoulders and mandible. |

|

Retrusion |

Moving a structure posteriorly. The opposite of protrusion. |

Table 1.3 Anatomic planes of the body. Used with reference to the anatomical position

|

Plane |

Description |

|

Median |

A plane in the midline of the body—it divides the body into equal right and left portions |

|

Sagittal |

Any plane parallel to the median plane, dividing the body into right and left portions. |

|

Coronal |

A plane at a right angle to a sagittal plane, dividing the body into anterior and posterior portions |

|

Transverse |

A horizontal plane that divides the body into upper and lower portions |

Body regions

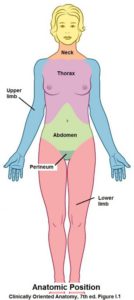

Gross anatomy can be described using a systems or a regional approach. In FMS 501, we use a regional approach to learn the organs and structures within certain body regions (see Figure 1.1). In other courses, we will study entire organ systems, such as the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

There are three regions of the body that are typically studied in anatomy classes:

The head and neck

The trunk

The limbs: Upper and lower

The trunk is subdivided into:

- thorax

- abdomen

- pelvis

- perineum

The upper part of the trunk, between neck and abdomen.

The region of the trunk between the thorax and pelvis.

Loosely used to describe the pelvic skeleton (hip bones) and the pelvic cavity within; the transition region between trunk and lower limbs.

The most inferior part of the trunk—the “nether region” between thighs and buttocks.

The vertebrate body plan

Humans are vertebrates, so they have body plan features in common with other vertebrates.

-

- A segmented axis containing the vertebral column (what does “segmented” mean?).

- Two pairs of limbs.

- A hollow central nervous system, consisting of a brain and spinal cord.

-

- A hollow digestive tube.

- Respiratory organs (air tubes, lungs) develop as outgrowths from the upper part of the digestive tube (= the pharynx). Note that fish also have respiratory organs (= gills) located in the region of their pharynx.

- The heart is located anterior (ventral) to the digestive tube.

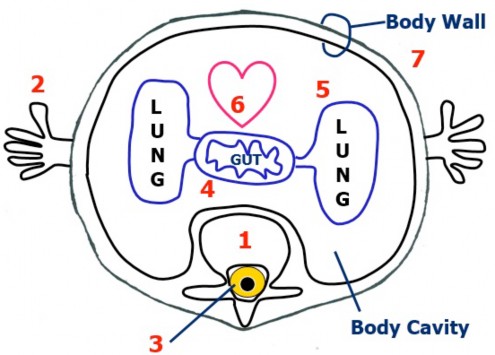

- The trunk contains organs (viscera) within a body cavity surrounded by a body wall.

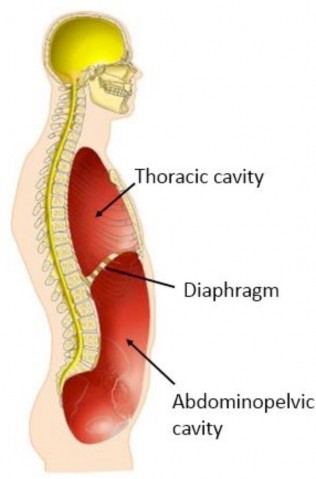

The body cavity

- The body cavity (cavum = hollow) or coelom is a specific term used to describe the central space within the trunk enclosed by the body wall. The diaphragm divides the body cavity into two parts:

- thoracic cavity and

- abdominopelvic cavity.

- The thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities contain:

- visceral organs (heart, lungs, stomach, urinary bladder, etc.) and

- serous sacs.

Serous sacs

A single layer of cells called a mesothelium lines the inside of the body wall and also covers the outer surfaces of many of the visceral organs contained within the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities. The mesothelium and the supporting connective tissue underlying it make up what is called a serous membrane. Serous comes from the term “serum”—which means “whey” = a clear watery fluid. Indeed, serous membranes secrete serous fluid, which makes them slippery. Serous membranes allow visceral organs and the body wall to move about without producing friction when they rub against one another.

The arrangement of the serous sacs within the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities can be modeled with an inflated balloon and your fist pushed into the balloon (Figure 1.4). The balloon is the serous membrane while the fist represents a visceral organ (lung or heart for example)—note that the part of the balloon’s surface that is away from the fist is curved and is the serous membrane that lines the inside of the body wall, while the part of the serous membrane in contact with the fist (i.e., the organ) conforms to the shape of the fist—the important point is that these two parts of the serous membrane are continuous and have a small space between them.

An important concept

All serous sacs have three parts:

1. The parietal layer of serous membrane lining the inside of the body wall

2. The visceral layer of serous membrane on the surface of the organ (actually, it is the outer layer of the organ itself)

3.

The serous cavity between parietal and visceral layers of serous membrane.

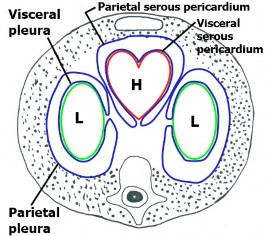

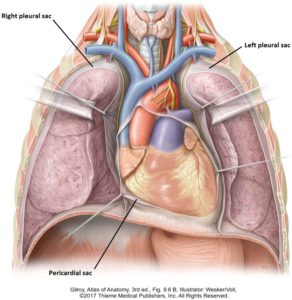

The thoracic cavity contains three serous sacs: two associated with the lungs and one with the heart. (See Figures 1.5 and 1.6.)

-

- The pleural sacs are serous sacs that surround the left and right lungs (pleur: a term denoting a relationship to the ribs or “the side” of the body). Note that there are two separate pleural sacs = right and left. Each pleural sac has a serous membrane called pleura and a cavity called the pleural cavity. The parietal pleura lines the inside of the thoracic body wall. The visceral pleura is the outer layer of the lung. The pleural cavity is a narrow space between the parietal and visceral layers of pleura, containing serous fluid. Do you see that the parietal and visceral layers of pleura face each other?

- The serous pericardium is the serous sac around the heart. It has parietal and visceral layers, separated by a pericardial cavity. More on this when we discuss the heart.

The abdominopelvic cavity contains one complicated serous sac.

The serous membrane here is called peritoneum (periteino– = to stretch over). The parietal peritoneum lines the inside of the abdominal body wall. The visceral peritoneum is the serous membrane on the outer surface of abdominal organs. The peritoneal cavity is between the parietal and visceral layers of peritoneum, containing serous fluid. Later on, you will see that the arrangement of peritoneum is much more complex than the serous membranes associated with the heart and lungs—BUT THE CONCEPT IS THE SAME!

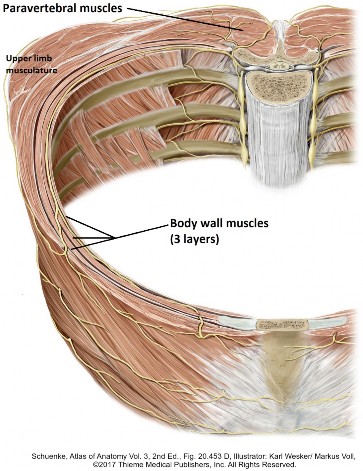

The body wall

The body wall surrounds the body cavities of the trunk. The thoracic and abdominal body walls are architecturally very similar; one difference being the presence of bones (=ribs and sternum) in the thoracic wall. By learning the basic concept of the body wall it will be a snap for you to adapt it to your descriptions of the thoracic and abdominal body walls. We’ll skim through this subject, leaving the details for the Dissection Lab. In a nutshell, here are structures that make up the body wall in the thorax:

- Skin (Integument)

- Thoracic cage

- Muscles

An organ consisting of an outer layer called the epidermis and a tough connective tissue layer beneath it called the dermis.

The skeletal elements underlying the thoracic body wall consisting of ribs, costal cartilages, the sternum, and thoracic vertebrae.

- Paravertebral muscles: As the name implies, these are located adjacent to the vertebral column in the back. They form an easily palpable longitudinal mass alongside the vertebral column.

-

Body wall muscles: Three layers in both thoracic and abdominal regions:

-

- External layer

- Internal layer

- Innermost layer

Fascia

(fasc- = a “band”)

- Fascia is dense connective tissue arranged in sheets and tubes throughout the body. It functions to bind together and support tissues and organs. Fascia serves to organize and compartmentalize the body into layers, forming “planes” that allow parts and layers to glide over one another. You will observe this layering when you dissect the cadaver. Fascia is a friend, allowing the dissector to separate layers of muscles and define planes containing nerves and blood vessels.

- Fascia has great importance to the surgeon in dividing and reflecting layers. Some fascia is thick enough to place sutures in. Fascia has clinical implications in walling-off or restricting the spread of infections and confining the growth of tumors.

- Fascia is is ubiquitous. It attaches to bones and cartilage and encloses visceral organs and muscles. The problem lies in the naming = anatomists love to name things, and sometimes naming schemes are inconsistent. Worse, different authors have different interpretations and thus different names for fascial layers, including using eponyms (e.g., Scarpa’s fascia) instead of descriptive names (e.g., membranous layer of superficial fascia). We will try to be consistent and keep things as simple as possible.

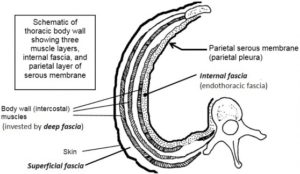

There are three categories of fascia in the body wall:

Superficial fascia lies directly beneath the skin—it is subcutaneous tissue (Sub-Q). It contains varying amounts of fat. This layer serves to insulate the body, gives the body its contours, and absorbs impact and pressure.

Deep fascia lies beneath the superficial fascia, associated with skeletal muscles. Deep fascia splits to surround the muscles in the body wall, forming an “envelope” around each muscle layer. Some books refer to deep fascia as investing fascia for this reason. Deep fascia also forms “capsules” around certain organs, such as salivary glands in the head. Deep fascia attaches to bones, becoming continuous with the bone’s periosteum.

Internal fascia lines the inner aspect of the body wall (thus defining the body cavity), lying between the parietal layer of serous membranes and the deepest layer of skeletal muscles in the body wall. Its main function is support: to be the “wallpaper paste” affixing the parietal layer of the serous membrane to the body wall. In the thoracic wall this layer is called endothoracic fascia, lying between the parietal pleura and body wall muscles. Likewise, in the abdominal body wall it is referred to as endo-abdominal fascia, located between the parietal peritoneum and the body wall muscles.

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.