-

Learning objectives

After completing this session, learners will be able to do the following:

-

- Define antimicrobial resistance and the mechanisms through which it occurs

- Describe the global size and scope of antimicrobial resistance

- Explain how and why antimicrobial resistance spreads and identify key drivers

Background

In 1928, Alexander Fleming made a discovery that would revolutionize the practice of medicine and prove to be one of the greatest public health advances in history. After a piece of mold contaminated his petri dish and produced a substance that killed off the bacteria he was studying, Fleming and others used this finding to develop penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic, which could cure common bacterial infections.

In the following years, additional antibiotics were discovered that formed the foundation for treating and preventing many of the deadliest diseases at the time, including tuberculosis (TB) and pneumonia. These new antibiotics were so effective in treating common illnesses that some believed the war against infectious diseases had been won.

Since Fleming’s time, similar advances with other antimicrobial agents have helped turn the tide against diseases like HIV and malaria. However, many microbes are able to mutate and evolve over a very short period of time. Some of these mutations make microbes less susceptible to the effects of antimicrobials, a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance. Sure enough, the first cases of bacterial infections resistant to penicillin began appearing only four years after it was put to large-scale use during World War II. Now, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is present in every corner of the globe and represents an increasingly serious threat to global public health.

Sources

Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014; WHO 2015.

Glossary term

antibiotic

antimicrobial resistance

antimicrobial agent

microbe

Did you know?

In a 1945 interview with the New York Times, Alexander Fleming, who won a Nobel Prize that year for his discovery of penicillin, warned that misuse of the drug could result in

selection for resistant bacteria.

Source: Rosenblatt-Farrell, 2009.

What is Antimicrobial Resistance?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), AMR “occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines, making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death” (WHO2020a).

In other words, resistance occurs when an antimicrobial has lost its ability to effectively control or eliminate a microbial infection against which it was once effective. The microbes are then considered resistant and can continue to replicate even when the antimicrobial is present. The microbes, not the human, become antimicrobial resistant. These resistant microbes can then spread among humans, animals, and even within water and soil.

While many people are aware

that bacteria can develop resistance to the antibiotics used to treat them (antibiotic resistance), as WHO’s definition points out, resistance also occurs in other microbes such as viruses, parasites, and fungi (collectively called antimicrobial resistance).

Sources

Australian Government 2017a; UK Research and Innovation 2021; WHO 2020a.

Glossary term

AMR: A serious global health threat

The WHO names AMR as one of the top 10 threats to global health.

-

Need to preserve existing antimicrobials

AMR has existed for as long as antimicrobials themselves; however, global concern has grown as drug resistance outpaces the discovery of new antimicrobial products, which are often time consuming and expensive to research and develop and may not be financially rewarding. Regarding antibiotics, for example, the WHO asserts that “almost all the new antibiotics that have been brought to market in recent decades are variations of antibiotic drugs classes that had been discovered by the 1980s” (WHO 2021), and notes that recently approved antibiotics and those in the clinical pipeline are not enough to address the growing global problem of AMR.

Global partners are increasingly paying attention to this challenge. For example, in July 2020, more than 20 biopharmaceutical companies committed to developing innovative antibacterial treatments—aiming to bring 2–4 new treatments to patients by 2030. But the research and development and market challenges still persist.

Because the rate of discovery for new antibiotics and other antimicrobials is so slow, it is paramount that existing antimicrobials are used appropriately and rationally (preserving their effectiveness) alongside efforts to discover completely new—or “novel”—antimicrobials.

-

Rising use of antimicrobials

And now for a global health paradox: Greater access to essential medicines, a major public health achievement, also can mean greater use of antimicrobials and opportunity for drug resistance to emerge and spread, especially if they are used inappropriately. The consumption rate of antibiotics in humans rose 39% from 2000 to 2015 and is projected to increase another 200% by 2030. These increases are attributed mainly to use in low- to middle-income countries. Additionally, animal consumption of antibiotics will increase an estimated 53% between 2013 and 2030.

-

Need for action

Infectious diseases know no borders, and international travel and commerce provide ample opportunity for AMR in one region to quickly escalate to a global crisis. It is critical that every country, regardless of income level, is concerned with and proactively takes steps against AMR. Containment will only occur with concerted, coordinated global action.

With inaction comes the very real risk of reversing the progress made against today’s public health challenges such as HIV, TB, malaria, maternal and newborn health, and safe surgery, and a likely resurgence of diseases of the past, including once-easily treated infections like pneumonia.

Sources

Klein et al., 2018; Pew Trust 2020; Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2016; Theuretzbacher U 2019; Van Boekel 2017; World Bank 2016; WHO 2019a; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020b; WHO 2021; WHO 2021b.

How does AMR occur?

-

Intrinsic and acquired methods of resistance

Some microbes are pre-programmed to be resistant to certain types of antimicrobials. This is known as inherent or intrinsic resistance. For example, gram-negative bacteria have a cell wall covered by an outer membrane that physically blocks some antibiotics from working.

Microbes can also acquire genes that code for resistance, known as acquired resistance, through two ways:

-

- gene mutation during replication (vertical transmission)

- exchange of genes between microbes (horizontal transmission)

Genetic mutations are rare spontaneous changes or errors that happen when microbes replicate. Occasionally, these mutations will change the microbe in a way that helps it resist the effect of exposure to an antimicrobial. These new resistant genes are then passed on to the microbe’s progeny, a process known as vertical transmission.

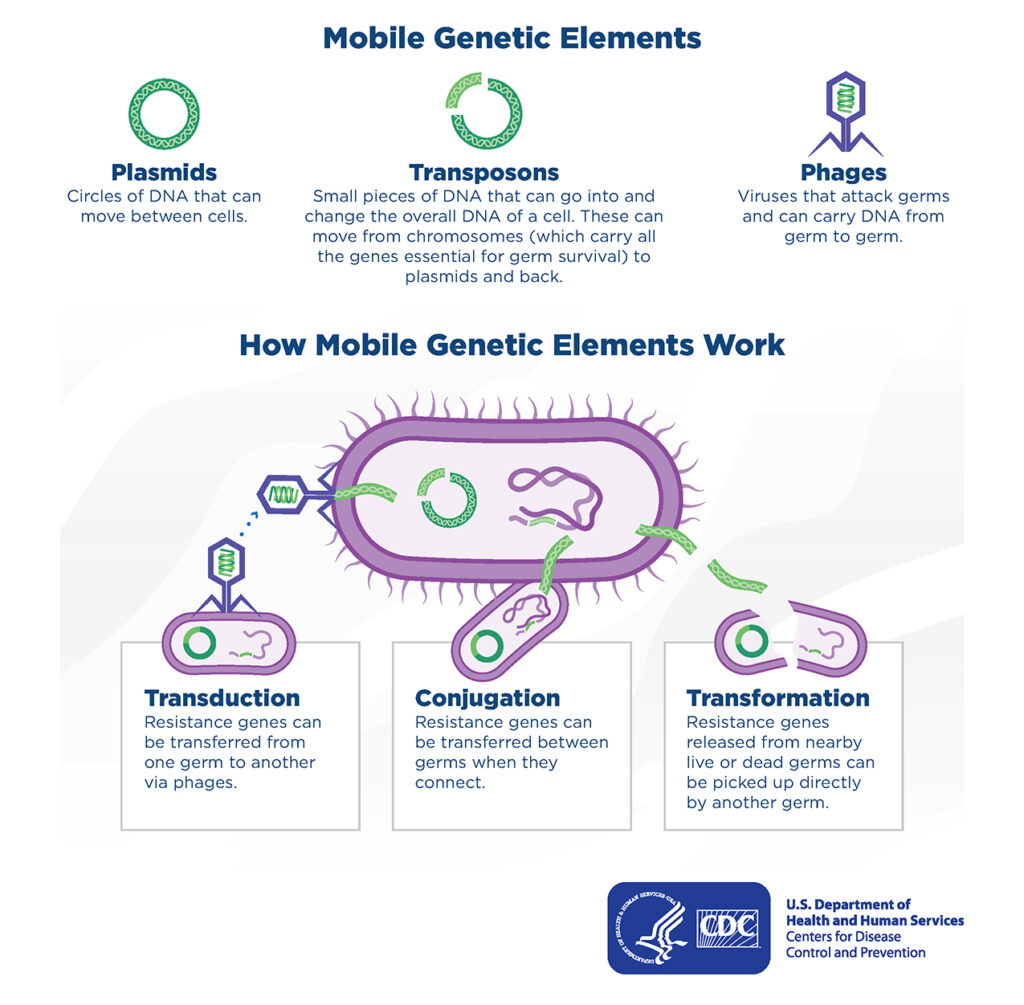

Microbes can also acquire resistance through horizontal transmission, in which genetic material is exchanged between microbes. For example, when bacteria come in direct contact with each other, small circular pieces of DNA found in the cytoplasm (plasmids) may be transferred through a process known as conjugation. While this is thought to be the main mechanism of horizontal transmission, bacteria may also pick up bits of DNA from the external environment (transformation), or through the transfer of DNA from bacteria-specific viruses known as bacteriophages (transduction). The graphic below illustrates how microbes can become resistant through horizontal transmission.

Sources

NIAID 2011; Todar 2011.

Mobile Genetic Elements:

-

- Plasmids: Circles of DNA that can move between cells.

- Transposons: Small pieces of DNA that can go into and

change the overall DNA of a cell. These can move from chromosomes (which carry all the genes essential for germ survival) to plasmids and back. - Phages: Viruses that attack germs and can carry DNA from germ to germ.

How Mobile Genetic Elements Work:

-

- Transduction: Resistance genes can

be transferred from

one germ to another

via phages. - Conjugation: Resistance genes can

be transferred between

germs when they

connect. - Transformation: Resistance genes released from nearby

live or dead germs can

be picked up directly

by another germ.

- Transduction: Resistance genes can

-

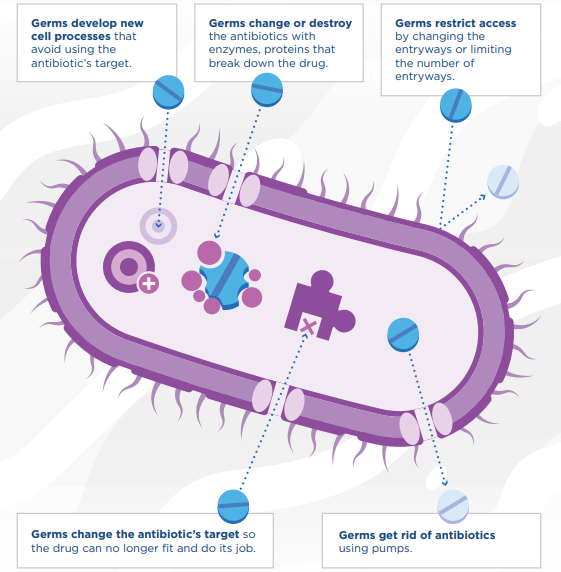

Molecular mechanisms of resistance

At a molecular level, the genetic materials discussed in the previous page provide microbes several different ways to resist the effects of antimicrobials: The microbe develops new processes that evade the antimicrobial’s target (mechanism #1 in the graphic below).

The microbe chemically modifies or destroys the antimicrobial (mechanism #2 in the graphic below)

The microbe physically blocks or removes the antimicrobial from the cell (mechanisms #3, and #4 in the graphic below)

The microbe alters the target site so that it is no longer recognized by the antimicrobial (mechanism #5 in the graphic below)

Sources

CDC 2019.

- Germs develop new cell processes that avoid using the antibiotic’s target.

- Germs change or destroy the antibiotics with enzymes, proteins that break down the drug.

- Germs restrict access by changing the entryways or limiting the number of entryways.

- Germs get rid of antibiotics using pumps.

- Germs change the antibiotic’s target so the drug can no longer fit and do its job.

-

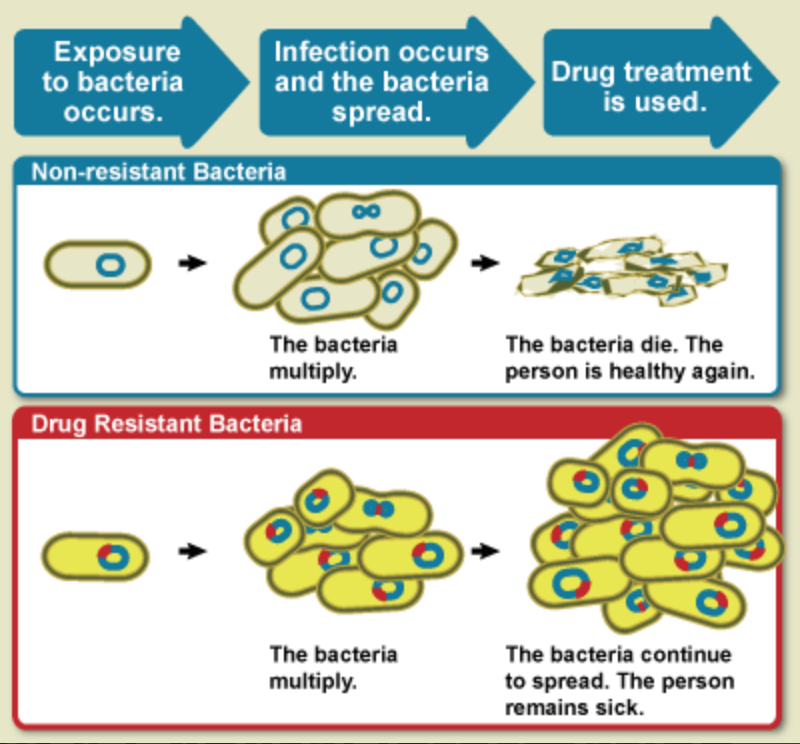

Selective pressure

Microbes that acquire resistance genes, either through vertical or horizontal transmission, will survive in the presence of a specific antimicrobial while the ones without the resistance gene will die. This selective pressure will leave resistant microbes behind, and with no competition for growth, they will multiply and spread as the graphic shows. Antimicrobials can actually create a situation where resistant microbes flourish, particularly when incomplete doses are used or when the antimicrobial is poor quality and lacks sufficient potency.

When microbes acquire resistance genes to more than one type of antimicrobial drug, they are referred to as multidrug-resistant organisms.

Sources

APUA 2020; NIAID 2011

Glossary term

How does AMR spread?

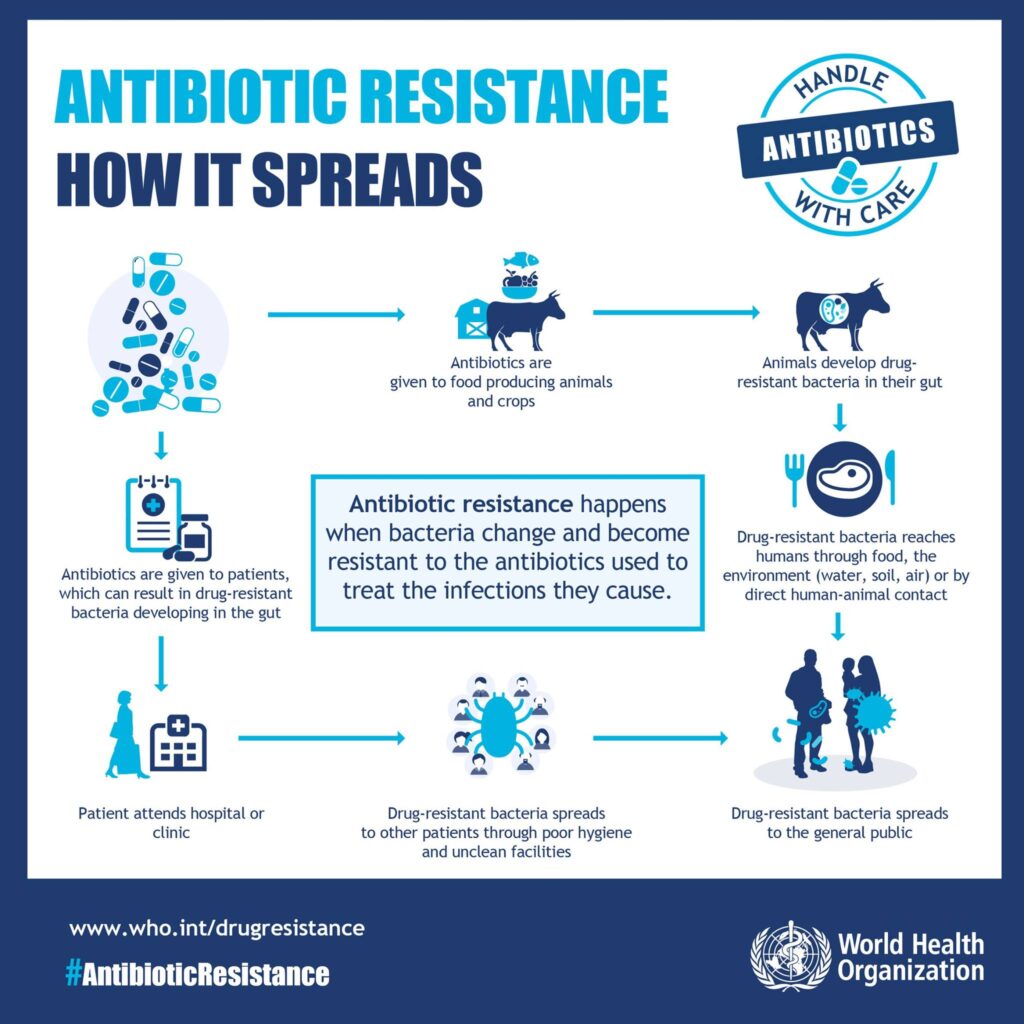

Antimicrobials are used for both human (medical) and animal (agricultural) purposes, both of which can facilitate the spread of AMR.

In agriculture, animals are often given antibiotics for treatment or to promote quicker growth. The resistant bacteria they carry can be passed to humans through food or direct contact or through crops contaminated with affected manure.

Humans can also develop resistant microbes through a natural adaptive process when they are treated with antimicrobials and also in health care facilities where unclean hands or contaminated objects can spread resistant microbes to patients who then spread them to the community.

Resistant microbes from animals and people can also end up in the environment—particularly water.

The figure below shows how antibiotic resistance can spread between animals, humans, and the environment.

Antibiotic resistance happens when bacteria change and become resistant to the antibiotics used to treat the infections the cause. There are two paths.

Path 1

- Antibiotics are given to food-producing animals and crops.

- Animals develop drug-resistant bacteria in their gut.

- Drug-resistant bacteria reaches humans through food, the environment (water, soil, air) or by direct human-animal contact.

- Drug-resistant bacteria spreads to the general public.

Path 2

- Antibiotics are given to patients, which can result in drug-resistant bacteria developing in the gut.

- Patient attends hospital or clinic.

- Drug-resistant bacteria spreads to other patients through poor hygiene and unclean facilities.

- Drug-resistant bacteria spreads to the general public.

Sources

ECDCWHO 2015b

Drivers of AMR

Any use of antimicrobials—even appropriate use—contributes to the development of resistance. However, unnecessary and inappropriate use of antimicrobials exacerbates AMR development and spread.

-

Improper use in humans

Globally, more than half of medicines are prescribed, dispensed, or sold inappropriately. Overuse and misuse of antimicrobials is a huge global problem. For example, antimicrobials are often unnecessarily used to treat acute viral conditions, such as the common cold or flu. Complex and interacting deficiencies across all levels of the health system, including legislation and regulation, supply chain management, quality assurance, prescribing and dispensing practices, and patient behavior contribute to inappropriate use. These areas, as well as strategies to combat AMR, are explored in depth in Antimicrobial Resistance, Part 2.

-

Improper use in animals

Antimicrobial products are used extensively for agricultural purposes, including for the treatment and prevention of illnesses and for increased growth promotion. In fact, in some countries, up to 80% of the total consumption of antibiotics that are medically important for humans is in the animal sector.

-

Accumulation in the environment

Excessive and inappropriate use of antimicrobials in both humans and animals also means that these compounds are accumulating in the environment—for example, through wastewater, sewage, and runoff. Hospital effluents and discharged wastes from antimicrobial manufacturing plants can also contaminate the rivers and soils with these compounds. The impact of such accumulation on the emergence of antibiotic resistance should not be understated. Most water quality legislation does not include provisions to monitor the concentrations of antimicrobial-resistant microbes in sewage or treatment plants.

Sources

CIDRAP 2019; Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014; WHO 2011; WHO 2017a.

Session summary

To recap, this session defined antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and briefly described its global scope. The session also explained and provided graphics for the molecular mechanisms through which AMR occurs. Finally, it identified the human, animal, and environmental drivers of AMR and how these drivers cause AMR to spread.

The next session discusses the threat AMR poses in more detail.

These materials were adapted from the Global Health eLearning Center, U.S. Agency for International Development.

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.