Case study 1: Margaret—Facial droop and slurred speech

question

Which of the following is the most significant risk factor for her current presentation?

The patient’s right-sided weakness and speech difficulty is consistent with a left-sided infarct, most likely in the MCA territory. Her imaging demonstrates a vessel occlusion rather than a hemorrhage. Of the choices listed above, her paroxysmal afib is the most significant risk factor for development of an ischemic stroke due to a cardioembolic event.

Stroke categories

question

It affects management (e.g., whether to give tissue plasminogen activator tPA.) and may affect prognosis.

- Major categories

- How do we decide what kind of stroke it is?

- TIA: Transient ischemic attack.

- Ischemic stroke.

- Small vessel (atherosclerotic or hypoperfusion).

- Large vessel (often embolic or hypoperfusion).

- Hemorrhagic stroke.

- Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH).

- Sub-arachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

- History: Onset, duration, patient’s past medical history, etc.

- Clinical findings: Neurologic exam.

- Imaging.

- CT usually done immediately to rule out bleed/determine whether patient may be a candidate for tPA.

- May require the increased sensitivity of an MRI, especially with new/small strokes.

Hemorrhagic stroke

- Clinical presentation

- Causes

- Pathophysiology

- Image findings

- Management

- Onset: SAH is usually sudden, ICH worsens over minutes to hours; ask for sx of SAH “sentinal bleeds”

- Patient may complain of the “worst headache of [their] life,” especially in subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Specific neurologic deficits depend of location of hemorrhage (see “localizing stroke” slide).

- Other complaints may include: Nuchal rigidity, vision changes, nausea/vomiting

Demographics: Seen most commonly in patients with HTN.

Primary causes (80%–85%)

- HTN.

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Secondary causes (15%–20%)

- Hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke.

- Stimulant drugs.

- Vascular malformation: Aneurysm, AVM, venous angioma, cavernoma, dural AV fistula.

- Coagulopathy: Hereditary, acquired, iatrogenic (anticoagulants, antiplatelets).

- Neoplasm.

- Trauma.

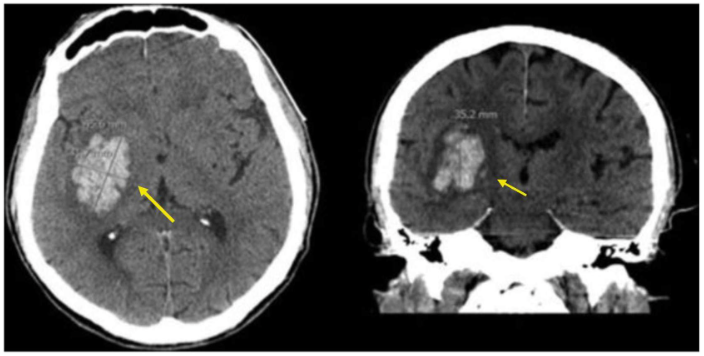

CT

Non-Contrast CT Findings (Examples)

- Often used for hyperacute stroke imaging can we/should we give tPA?

- Benefits: Allows for fairly accurate measurement of hematoma volume, and can be done serially to monitor evolution.

- Findings

- First 72 hours: Bleed shows up as hyperintensity, with surrounding hypodense edematous area.

- 3–20 days after initial stroke: Lesion becomes less intense and may appear to shrink; may develop irregular, abscess-like ring border.

- Contrast CT-angio (“CTa”) can help determine risk of hematoma enlargement “spot sign” = contrast extravasation into hematoma.

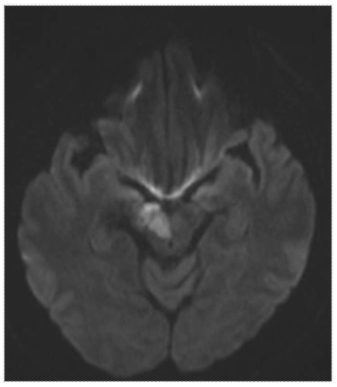

MRI Benefits vs. CT

- Higher degree of sensitivity for detecting small strokes.

- Deoxyhemoglobin is identifiable as a blood degradation product in early strokes, due to its paramagnetic properties.

- Good for detecting causes of secondary intracranial hemorrhage, (e.g., vascular malformations).

Do not give tPA!

The goal is to stop the bleed, not make it worse.

- Patients often require treatment in the ICU or a dedicated stroke unit.

-

Bleeding management: All anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs should be discontinued, at least temporarily, upon presentation.

- HTN management:

- For systolic BP 150–220 mmHg, lower to ~140 mmHg.

- For systolic BP > 220 mmHg, aggressively lower to ~140–160 mmHg.

- Other considerations:

- Management of intracranial pressure/mass effect (mannitol commonly used).

- Intubation/mechanical ventilation.

- Seizure prophylaxis (levetiracetam [Keppra] most commonly used).

- +/- surgical evacuation of hematoma.

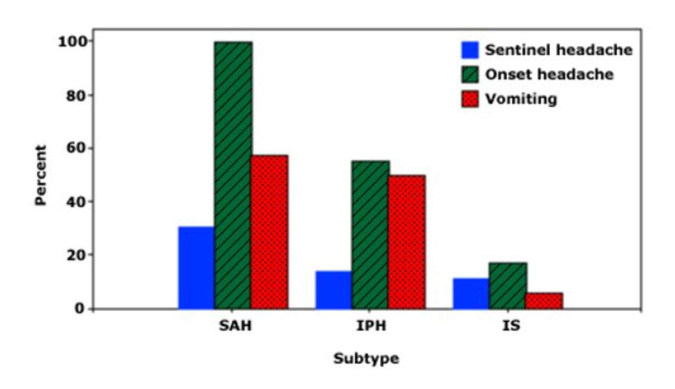

Headache and vomiting in stroke subtypes

The frequency of sentinel headache, onset headache, and vomiting in three subtypes of stroke: Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), intraparenchymal (intracerebral) hemorrage (IPH), and ischemic stroke (IS). Onset headache was present in virutally all patients with SAH and about one-half of those with IPH; all of these symptoms were infrequent in patients with IS.

Data from: Gorelick PB, Hier DB, Caplan LR, Langenberg P. Headache in acute cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 1986; 36:1445.

Similar considerations apply to some prophylactic treatments historically used to prevent medical complications after ICH. Use of graduated knee- or thigh-high compression stockings alone is not an effective prophylactic therapy for prevention of deep vein thrombosis, and prophylactic anti-seizure medications in the absence of evidence for seizures do not improve long-term seizure control or functional outcome.

Greenberg SM, Steven M. Greenberg, Ziai WC, et al. 2022 guideline for the management of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. Published May 17, 2022. Accessed May 31, 2022.

- Demographics

- Pathophysiology

- Etiologies

- Clinical presentation

- Management

Most common cause of stroke (87%).

Lack of perfusion to a certain area of the brain due to blockage or disruption of arterial blood flow.

- Artero-embolic (large-artery disease): Atherosclerotic disease.

- Lacunar (small vessel disease): Microatheroma, microembolism.

- Cardioembolic: Afib, valvular disease.

- Other: Arterial dissection, vasospasm, vasculitis, hypercoagulable states.

- Idiopathic.

-

Specific neurologic deficits depend on area of the brain affected by stroke (see “stroke localization”).

-

Onset of ischemic stroke can be “stuttering” while embolic stroke is usually sudden, similar to hemorrhagic events.

-

Recognition of stroke may be delayed if person lives alone or deficits are subtle important: can affect management (+/- tPA).

-

Severe headache less likely with ischemic events—you may recall from the previous section that severe headache is much less likely with ischemic strokes.

-

Current recommendation = ok to give tPA if:

- No evidence of hemorrhage on initial imaging (usually non-contrast CT).

- Stroke is believed to have occurred within 4.5 hours of “last known normal”

- Stroke is considered “disabling” to individual (perceived benefit of intervention > risk).

Endovascular intervention

- Thrombectomy decreases morbidity and mortality in major acute ischemic strokes.

- Goal reperfusion time: 90 mins.

Blood pressure

- Goal BP < 180/105 (> 120 systolic); prefer IV labetolol, nicardipine, or clevlidipine.

Oxygenation

- Goal is > 94% SaO2.

- Patients may require intubation due to compromise of respiratory drive (esp if brainstem involvement).

Aspirin, Statin therapy and DVT prophylaxis

- Initiate as soon as safe.

Imaging

- Non-contrast CT

- MRI

- Findings

First-line imaging in acute stroke.

Advantages

- Quick to perform can determine if patient is candidate for tPA.

- Less expensive than MRI.

Disadvantage

- Small infarcts may not be discernible on CT; MRI has better sensitivity and is often obtained after CT.

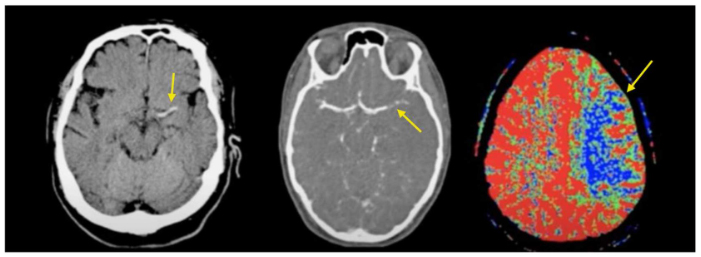

CT Stroke Series (left to right): Non-contrast CT demonstrating acute thrombus; CT angio demonstrating occlusion of L MCA; decreased perfusion.

Hyperacute

- Hyperdense segment of occluded vessel may be seen; usually MCA.

- Loss of gray-white matter differentiation in affected area.

- Cortical hypodensity with parenchymal swelling and gyral effacement.

Acute

- Continued parenchymal swelling and gyral effacement mass effect.

Subacute

- Edema begins to subside.

- “CT fogging phenomenon” = cortical petechial hemorrhages increase attenuation of affected cortical areas, which can lead to affected area being mistaken as normal.

Chronic

- Edema diminishes even further; begin to see gliosis as hypodensity on CT.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- What is it?

- Why do they matter?

- Demographics

- Try to avoid using the term “mini stroke.”

- TIAs are transient ischemic events of the brain, spinal cord or retina, similar in presentation to a stroke but involving no lasting neurologic deficit.

If there are no lasting deficits, why do they matter?

- More than one-third of patients who experience a TIA will have a major stroke within one year.

- Highest risk is within the first 48 hours following a TIA.

Often occur in the elderly or people with risks for extensive small vessel disease (smoking, diabetes).

The American Heart Association's About Stroke website has more information (see the Professionals tab).

Note

TIAs are reversible by definition.

- Clinical presentation/diagnosis

- Management overview

- TIA Management

- Prevention

- Involve brief focal neurologic or speech deficit, depending on affected area.

- Usually last < 5 mins, but can be up to 1 hour in duration.

- R/O stroke: Most hospitals begin workup with appropriate stroke protocol.

- Further workup (if no stroke demonstrated):

- Sleep apnea workup.

- Cardiology workup: r/o PFO (Patent Foramen Ovale).

- Including echo with bubble study.

- Carotid imaging: If > 70% stenosis, significant risk of recurrent event.

- A1C.

- LDL.

Must address any underlying etiology.

- Blood pressure management.

- High-dose statin.

- Antiplatelet therapy.

- Blood glucose control.

- Dietary changes:

- Reduction in carbohydrate (sugar), fat.

- Exercise.

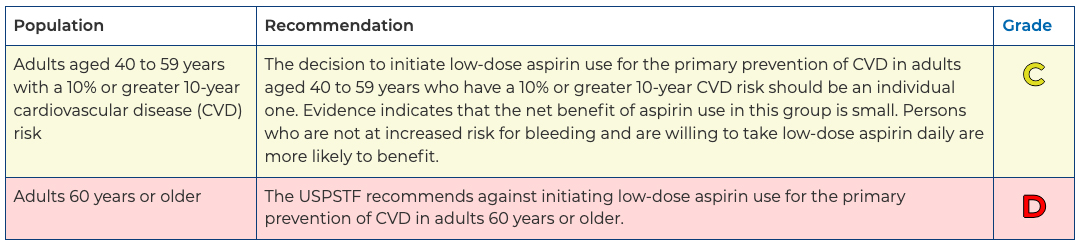

Recommendation summary

Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease: Preventive Medication. Final Recommendation Statement. United States Preventive Services Taskforce. April 26, 2022.

Secondary stroke prevention

Ischemic/Thrombotic stroke

Blood pressure control is key once the acute treatment phase has passed! < 140/90 (absolute numbers are somewhat controversial; some suggest SBP < 130).

Aspirin (low dose) OR clopidogrel (dual antiplatelet should probably be managed by specialists—see UpToDate review of anticoagulation in secondary stroke prevention).

- asa-dipyridamole has some evidence that it may be superior to asa alone, but HA is a limiting side-effect.

High-intensity statin reduces risk.

If atrial fibrillation, consider warfarin or DOAC (e.g., rivaroxaban).

- Calculate CHA2DS2-Vasc score and follow guidelines:

- One pt for HF, Htn, DM, vasc, F, age 65–74.

- Two pts for stroke, TIA, age > 75.

> 70% Carotid artery stenosis refer for consideration of stenting

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.