Patient 1: Emma—17-year-old girl with headaches

This is most likely a migraine headache. See the screening exam below.

- Screening exam (The 4-minute neuro exam)

Why practice (on anyone who will let you)?

- So you’ll actually do it.

- Do it the same way, in the same order, every time.

When?

- When you clinically suspect there is little to find (e.g., confirmatory for tension headache).

- When you are looking for gross abnormalities (e.g., sports physical; early diabetes physical; when admitting a patient to the ward for something else, but you should document the exam such as atrial fibrillation or chemotherapy where a stroke or peripheral neuropathy could become an issue).

My screening exam. Practice in the same order every time!

- Interview: Language and speech.

- Cranial nerves

- “Grossly intact” vs. “in detail” = I paid careful attention vs. checking every nerve.

- Document using these terms.

- “Grossly intact” vs. “in detail” = I paid careful attention vs. checking every nerve.

- Fundoscopic exam.

- Motor: Bulk, tone, and strength.

- Sensory: Position, light touch, pin-prick/temperature.

- Reflexes

- Special: Cerebellar, coordination, tremor, gait.

Exam Technique Pearls

- CNs-accommodation: Easier to see if you hold your finger at 2 feet then move it very quickly to 6 inches (pupils accommodate quickly).

- Motor: Quick comparison of side-to-side.

- Sensory: What to check and why, comparison.

- The dreaded sensory level

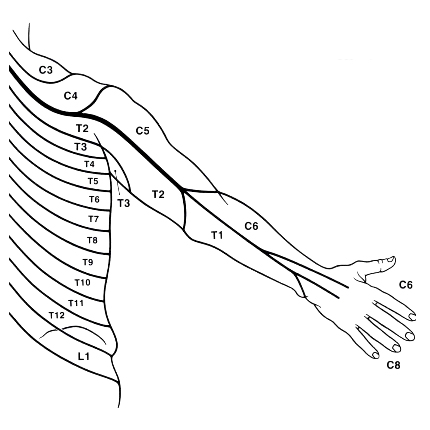

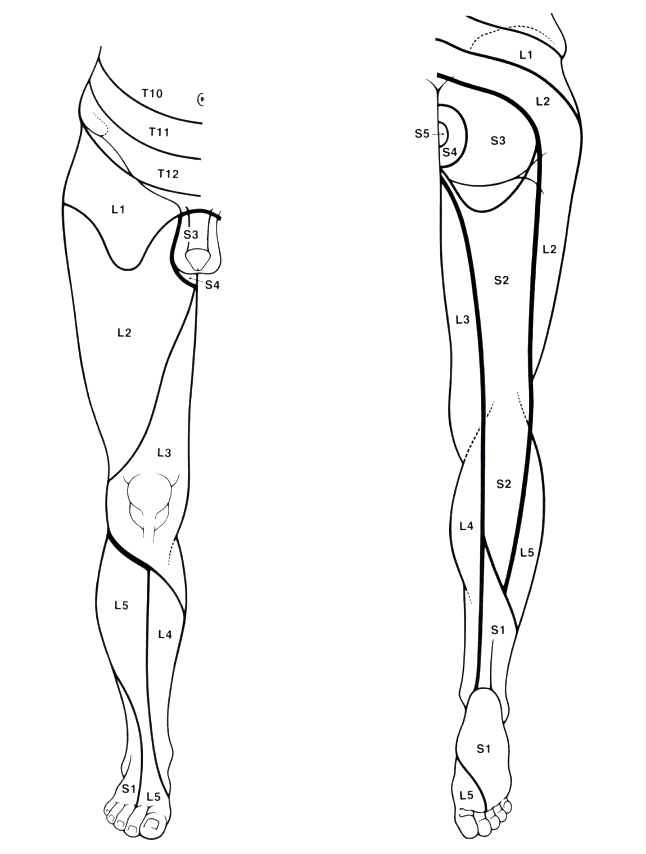

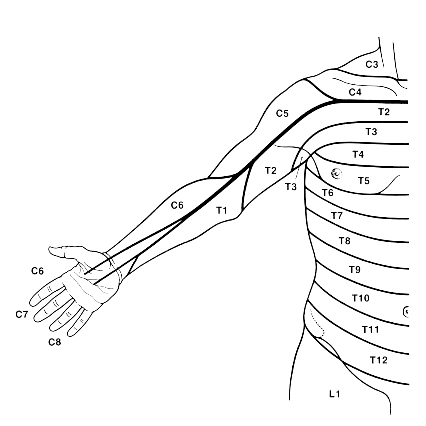

Learning dermatomes or knowing where to find them

- The dreaded sensory level

- Reflexes: Relaxation and augmentation

- It’s all in the swing – hold hammer at the end loosely.

- Romberg meaning? – It tests position sense.

- Tremor: Put a piece of paper over the hands to detect fine tremor; cogwheeling = tremor + rigidity.

- Gait: Watch for uneven gait and shuffling as the patient walks into the room or across the room.

Scale

Motor

5 = Normal

4 = Weak

3 = Can move against gravity

2 = Can move across gravity

1 = Flicker

0 = No movement

Reflexes

4 = Hyperactive

3 = Slightly Increased

2 = Normal

1 = Decreased

0 = Absent

Note: Hypothyroidism produces delayed recovery.

Patient 2: George—64-year-old man can't sleep

- Peripheral neuropathy. Most likely it is diabetic neuropathy or carpal tunnel (median nerve).

- Alcohol neuropathy or B12 neuropathy (especially if the patient is on metformin or a proton-pump inhibitor) should be considered.

Neurological exam

- Exam would include motor and strength testing of the upper extremities with comparison between the affected side and the unaffected side.

- Phalen and Tinel signs may be helpful, though their usefulness is controversial—likelihood ratios are 1.3 and 1.5, respectively, but I find them clinically useful at times. (See McGee, EBM Physical Diagnosis, for details.)

- Exam of the lower extremities for sensation, strength, and reflexes, as well as a complete diabetes foot exam, would be appropriate.

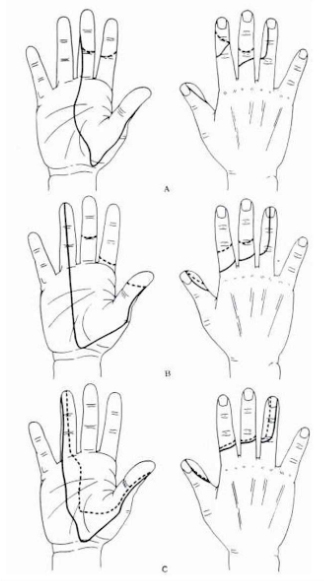

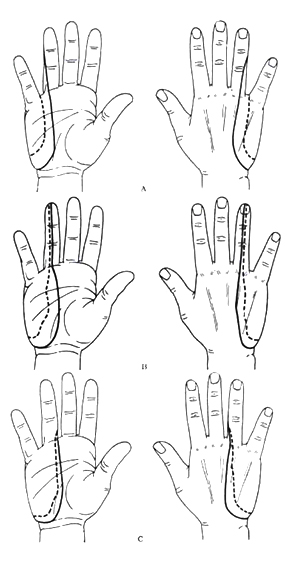

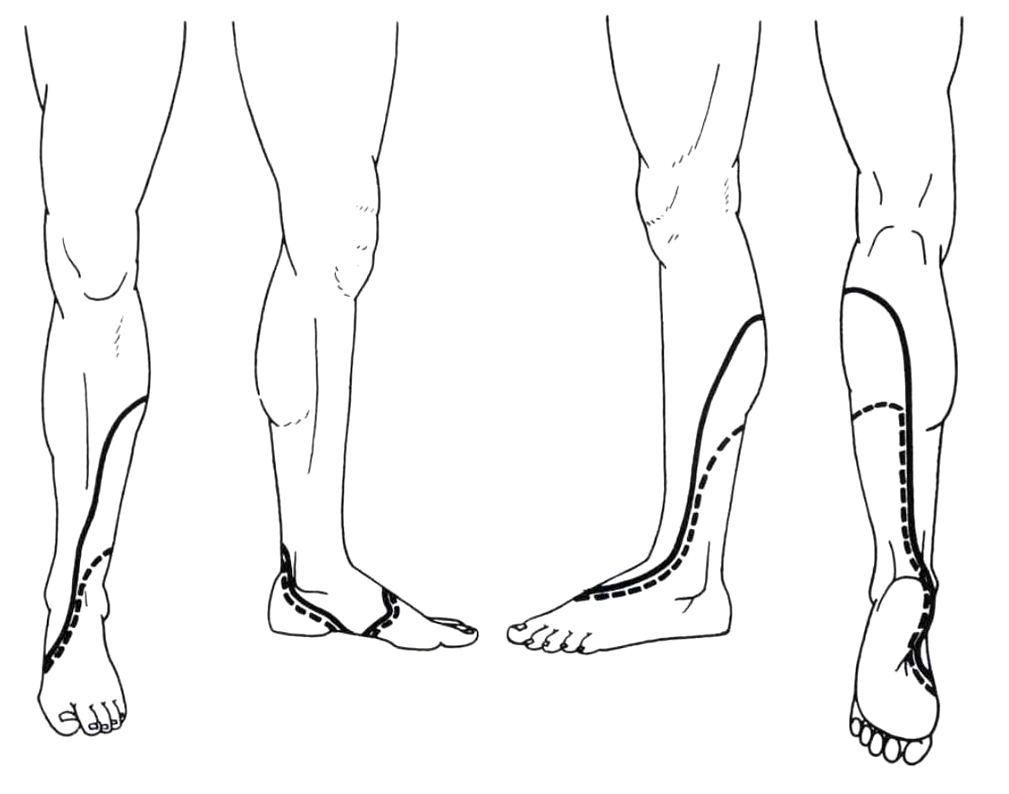

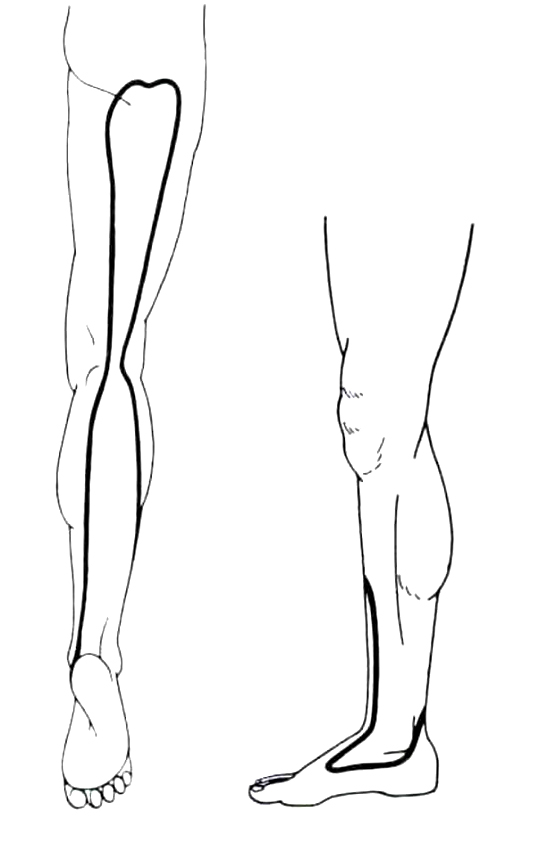

There is considerable variation and overlap.

This variation also applies to the innervation of the fingers, but the thumb is usually supplied by C6 and the little finger usually by C8 (see Inouye and Buchthal (1977) Brain 100: 731-748).

Patient 3: Darius—Days of fever and chills

This is most likely cauda equina syndrome, which is a medical emergency and requires urgent surgical consultation.

- Complete neurological examination of the lower extremities and a sensory level should be done, with comparison of strength, sensation, and reflexes to exclude a systemic disease process.

- Peri-anal sensation and rectal tone are an important part of the examination for cauda equina.

- You’re probably thinking that this exam is embarrassing; while that is true potentially for you and the patient, this is a life, or at least mobility-threatening condition, and I often will explain to the patient that if they feel embarrassed, I am happy to talk it through with them or to have a chaperone in the room, while doing everything possible to protect their privacy. I am always careful to explain both what I am doing and my findings as I go along.

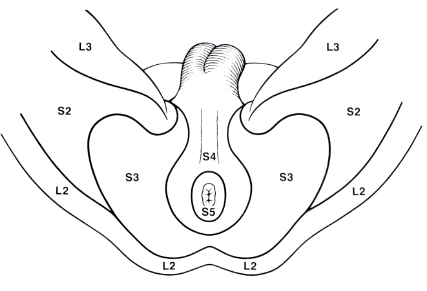

Approximate distribution of dermatomes on the perineum

See Inouye and Buchthal (1977) Brain 100: 731–748.

Patient 4: Rachel—Recurrent low-back pain

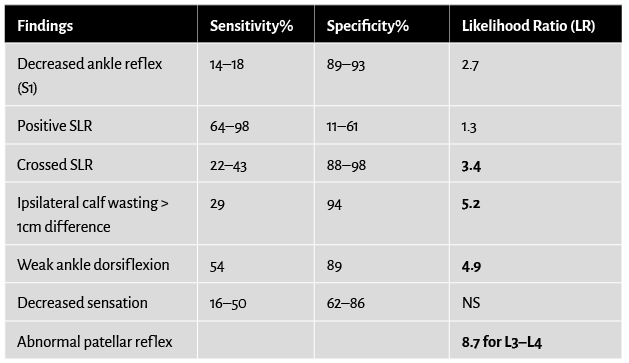

Positive crossed straight leg raise.

Rationale

In this case, the answer options did not include ipsilateral calf wasting or weak ankle dorsiflexion. Therefore, a crossed straight leg raise is the most predictive of the answer options given. See likelihood ratios below. Note significant variation from person to person in sensory/dermatomal findings.

Find a partner or friend and practice your neuro exam!

Image credits

Unless otherwise noted, images are from Adobe Stock.