It is very difficult to spend a week on a hospital medicine rotation without encountering an abnormal sodium value. Hypernatremia is easy to evaluate and manage, so we will start there.

It is very difficult to spend a week on a hospital medicine rotation without encountering an abnormal sodium value. Hypernatremia is easy to evaluate and manage, so we will start there.

Hypernatremia

First, correct the volume status. If you think the patient is volume down, start with a bolus or two of ringers (130 mEq/L sodium) or normal saline (154 mEq/L sodium). On recheck, the sodium will often be moving in the right direction.

- Once the patient is euvolemic, calculate the free water deficit using an online calculator such as MDcalc. This will provide you with an estimate of how much total D5W the patient needs to reach a certain sodium goal.

- Start D5W (1/2 NS is another option) at a rate a little slower than you think will be necessary and trend the sodium. Adjust the rate as necessary. Better to go too slow than too fast.

- The etiology of hypernatremia is that the patient either did not have access to free water, perhaps due to an underlying condition such encephalopathy, being stuck on the floor for a prolonged time with a leg fracture, or their brain is no longer appropriately regulating their sodium.

Two common examples:

- a patient with advanced dementia no longer feels thirsty, has poor PO intake and is not drinking enough water

- a significantly disabled person without the ability to get water or isn’t being inadequately cared for. We have a very strong drive to drink water to prevent hypernatremia.

Aim for a correction rate of no more than 10 mEq per day. The downside of going too slow is that the patient may be hospitalized slightly longer. The downside of going too fast is cerebral edema. Hypernatremia is, in general, easy and straightforward to deal with. This is in contrast to . . .

Hyponatremia

Below are several frameworks for evaluating a hyponatremic patient. Used together, they can help guide your management decisions.

Important or unimportant? On the inpatient side of medicine, not all hyponatremia requires a big evaluation.

Sodium Levels?

-

Sodium >130

Not the reason for admission, treat their acute illness and optimize volume status. Persistent mild hyponatremia can be further evaluated on an outpatient basis

-

Sodium 126–130

Not the reason for admission, treat their acute illness and optimize volume status, hold obviously offending medications, (hydrochlorothiazide etc). If worsening, lab testing may be warranted.

-

Sodium 120–125

Now an important inpatient issue. Patients can be symptomatic in this range. Sometimes the reason for admission. Don't rapidly correct the sodium level, but risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome still low.

-

Sodium < 120

Significant problem. Patients often symptomatic, sometimes severely so. Often, there are multiple competing etiologies, (for example use of an SSRI, hydrochlorothiazide, volume depletion, and sepsis). Warrants lab testing and further workup. The risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome is higher in this group, so be very careful not to rapidly correct the sodium level. Trend sodium frequently, maybe q4 hours, or even q2 hours if worsening or rapidly correcting.

-

Sodium < 105

Big problem and fortunately rare. Highest risk of osmotic demyelination syndrome, high risk of rapid sodium correction. Needs to be in the ICU. Probably a good idea to involve nephrology. Consider proactive use of DDAVP, or at least be ready to react to overcorrection. Trend sodium very frequently, maybe q2 hours at first, needs lab testing and likely foley catheter for strict urine output monitoring.

Acute or Chronic?

Acute hyponatremia is rare on the hospital medicine service. If you are unsure about the acuity, hyponatremia should be treated as chronic. Classic acute presentations are someone who finished a marathon or similar and has been aggressively hydrating, or someone drinking a lot of water while doing drugs at a music festival. Rarely will you have a normal sodium value less than 48 hours prior.

If you are confident that the hyponatremia is acute, the management is usually letting their body pee out the excess free water. If the patient is seizing, or you suspect their brain is herniating from cerebral edema, give hypertonic saline ASAP, generally 100cc of 3% saline, or in a pinch give an amp of sodium bicarbonate from the code cart, which is 50cc and 8.4% Na.

Obviously, these very sick patients should be managed in the ICU. The medical floor level patients usually pee for a day and the sodium normalizes.

The rest of this post refers only to chronic hyponatremia because it is what you will be managing in the hospital.

Hypervolemic, Euvolemic, or Hypovolemic?

If the patient is obviously volume overloaded from CHF, cirrhosis, or renal failure, the treatment is to get fluid out of their body with diuresis, dialysis, etc. You don’t usually need diagnostic testing. Rarely, your patient will be “total body fluid up, intravascular volume down,” and despite having obvious anasarca will have their sodium improve with volume resuscitation. Generally, these patients are chronically ill and have advanced heart or liver failure.

When they are not obviously volume overloaded, it can be difficult to tell the exact volume status of your patient. Severely hyponatremic patients (< 120) have more than just volume depletion causing their low sodium. If you suspect your patient is volume down, be slow with the fluids at first, as patients with a major component of volume depletion can rapidly correct their sodium after volume resuscitation.

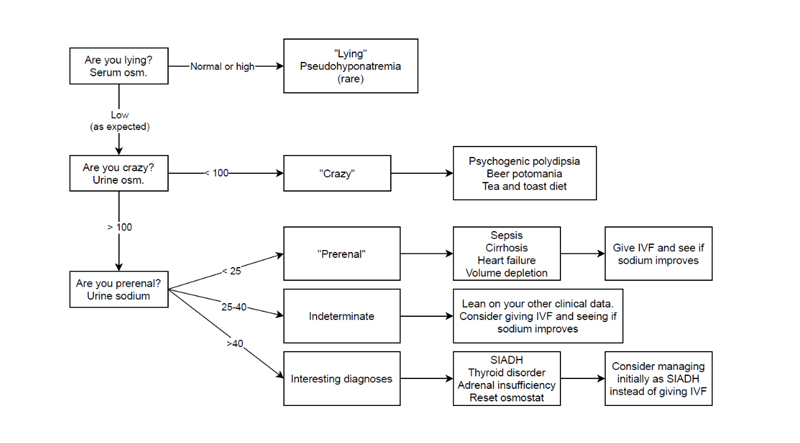

Serum Osms, Urine Osms, Urine Sodium

I learned the following framework in residency, it is incomplete, imperfect, and unprofessional but easy to remember and often helpful. Up-to-date has a much more thorough flow chart.

This chart is most useful with hypo and euvolemic patients. The most useful test is urine sodium because it can help you decide whether your first step is to restrict fluid (treating as SIADH) or starting IV crystalloid. Unfortunately, diuretics will give you a falsely elevated urine sodium.

Finally, Management

Ultimately, management is diagnosis and situation specific. When managing hyponatremia, the most important thing is to carefully monitor to avoid overcorrection. Try not to let the sodium go up by more than 6–8 mEq in the first 24 hours. Keep a close eye on the urine output, because high urine output of dilute urine after volume resuscitation if a sign of impending rapid correction of sodium.

To avoid or treat overcorrection, there are two strategies to lower the sodium level:

-

- Escalating rates of D5W.

- This option is more extreme, giving DDAVP (desmopressin, synthetic ADH) +/– D5W. Until you are comfortable with DDAVP use, there is no shame in consulting nephrology for help. Use of DDAVP in hyponatremia is a big topic and requires ICU level of care.

Check out this excellent article on the subject from EMcrit and PULMcrit.

One Final Tip

If it is unclear why the patient is hyponatremic (euvolemic hyponatremia with multiple potential etiologies), and their sodium is persistently drifting down into dangerously low levels overnight, it sometimes makes sense to:

-

- make the patient NPO except meds.

- stop IV fluid (if they are getting any).

- give them salt tabs overnight.

This isn’t very pleasant for the patient, but if salt is going in and the patient isn’t drinking water, the sodium will start to go up. Note that supplemental urea can be used instead of salt tabs, and in the long term, urea is regarded as a better option.

Image credit: Eric Tanenbaum.