Suggested reading

insert link + PDF (these are placeholders now)

Suggested reading

insert link + PDF (these are placeholders now)

Suggested reading

insert link + PDF (these are placeholders now)

Suggested reading

insert link + PDF (these are placeholders now)

Diabetes Mellitus is a condition characterized by hyperglycemia. In general, hyperglycemia results from either lack of insulin, as in Type 1 DM, or insufficient insulin to overcome underlying insulin resistance, as in Type 2 DM. Insulin deficiency or impaired action of insulin lead to disordered glucose homeostasis with abnormal carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism and to characteristic end organ disease involving the kidneys, nerves, eyes, and vasculature. These are seen in both types 1 and 2 DM.

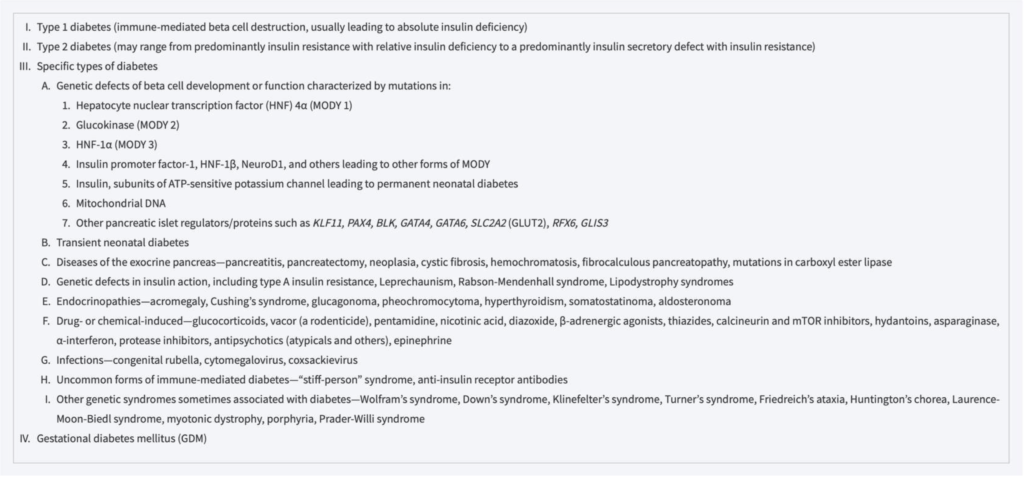

Although Types 1 and 2 DM are our main focus here, because of the large number of people affected by these conditions, you should have some familiarity with other types of diabetes mellitus, which will be briefly reviewed.

Maturity onset diabetes of the young, or MODY, and monogenic diabetes result from genetic defects that are transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern. Conditions that damage the pancreas can cause diabetes mellitus if too much insulin-secreting capacity is lost. This is a broad group with damage resulting from disorders such as pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, and hemochromatosis, injury or surgery, and other causes listed in the table below.

Rare mutations affecting the insulin receptor have been identified, and they cause hyperglycemia from severe insulin resistance.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has features similar to Type 2 DM, with insulin resistance as a major factor in its development.

Table 396-1. Etiologic classification of diabetes mellitus.

Abbreviation. MODY: maturity-onset diabetes of the young.

Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine.

Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Types 1 and 2

Diabetes mellitus has had various classifications over the years, and the current approach is to base classification on underlying pathogenesis.

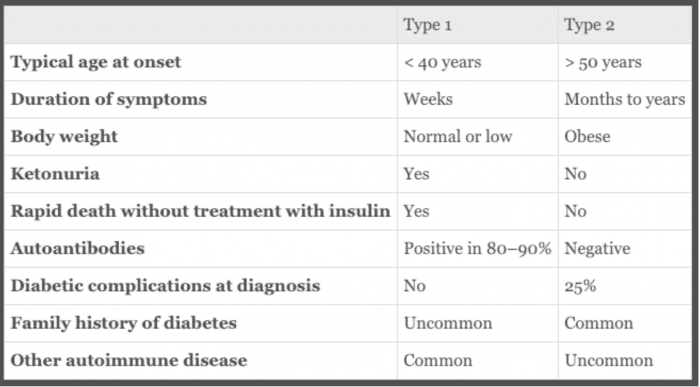

Box 20.12. Classical features of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MWJ, Hobson RP, Britton R, Davidson LS. Davidsons Principles and Practice of Medicine. 23rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2018.

For years, the two terms in use were “childhood-onset diabetes mellitus” and “adult-onset diabetes.” These categories described the most common ages of onset for what we now call Type 1 DM and Type 2 DM but didn’t reflect pathophysiology or the fact that “childhood onset” diabetes can occur any time in life (although it typically presents in childhood and adolescence). Subsequently, the terms “insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus” (IDDM) and “noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM)” came into use but were problematic because although Type 1 diabetics have no or very little insulin and will go into ketoacidosis without insulin, many Type 2 diabetics require insulin for control of hyperglycemia. Over the years, most Type 2 patients have ongoing loss of insulin-secreting capacity, and some become severely insulin deficient and have features of both Type 2 and Type 1. Currently the accepted diagnostic terms are Type 1 and Type 2 DM.

Most T1 diabetics are diagnosed before the age of 30, but it is increasingly recognized as a new diagnosis in people over 30 years old. Most T2 diabetics present after age 40, but T2 DM is increasingly diagnosed in obese children, adolescents, and young adults.

-

Type 1

-

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

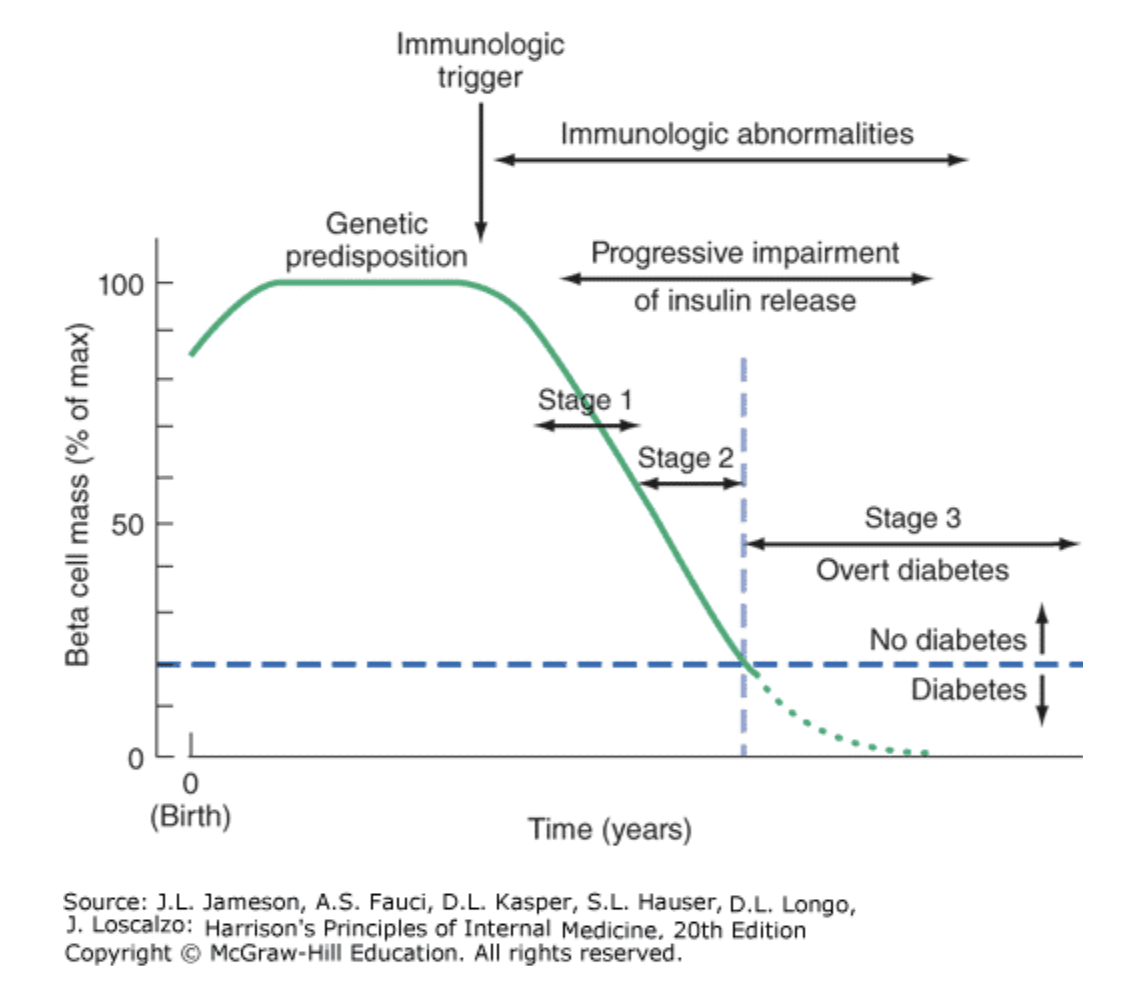

Type 1 DM results from an autoimmune process directed against the pancreatic islet beta-cells. We now know that the process that leads to beta-cell loss of function starts years before diabetes is diagnosed clinically.

In the case of Type 1 DM, the preclinical phase is asymptomatic. One focus of research is to identify patients with pre-clinical diabetes and intervene to prevent progression. At this time, no such treatment is available. Overt diabetes occurs when beta-cell mass drops below 20% of normal.

Figure 396-6. Temporal model for development of type 1 diabetes. Individuals with a genetic predisposition are exposed to a trigger that initiates an autoimmune process, resulting in the development of islet autoantibodies and a gradual decline in beta cell function and mass. Stage 1 disease is characterized by the development of two or more islet cell autoantibodies but the maintenance of normoglycemia. Stage 2 disease is defined by continued autoimmunity and the development of dysglycemia. Stage 3 is defined by the development of hyperglycemia that exceeds the diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes. The downward slope of the beta cell function varies among individuals and may not be continuous. A “honeymoon” phase may be seen in the first 1 or 2 years after the onset of diabetes and is associated with reduced insulin requirements. Adapted and modified from ER Kaufman: Medical Management of Type 1 Diabetes, 6th ed. American Diabetes Association, Alexandria, VA, 2012. Jameson JL. Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

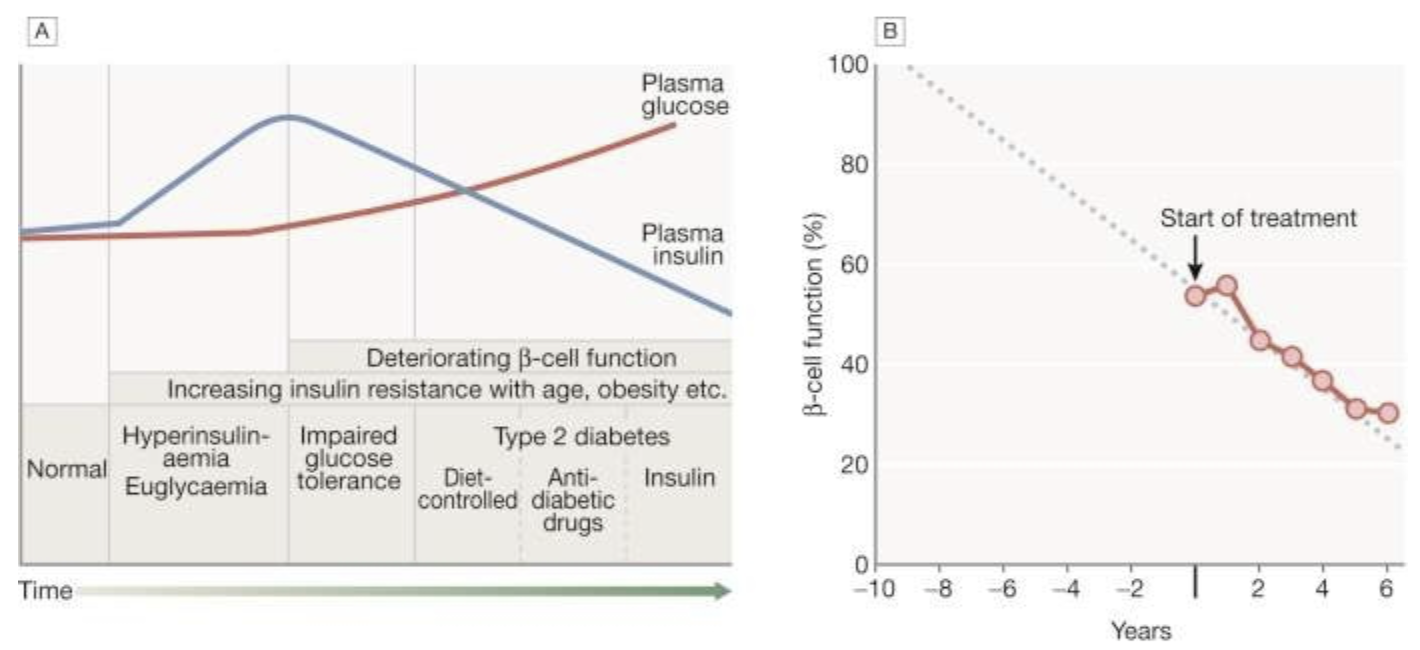

Type 2 DM results from the combination of insulin resistance and inadequate insulin secretion. As long as insulin secretion is sufficient to overcome insulin resistance, hyperglycemia doesn’t occur, and you can’t make the diagnosis of DM. However, as beta-cell function declines and insulin secretion drops, hyperglycemia develops and Type 2 DM is diagnosed.

Insulin resistance is a major component of Type 2 DM and is felt to play a major role in the comorbidities of Type 2 DM through mechanisms not yet fully understood. Insulin resistance is addressed in more detail in its own upcoming session.

Fig. 20.8 Natural history of type 2 diabetes.

A. In the early stage of the disorder, the response to progressive insulin resistance is an increase in insulin secretion by the pancreatic cells, causing hyperinsulinaemia. Eventually, the β cells are unable to compensate adequately and blood glucose rises, producing hyperglycaemia. With further β-cell failure, glycaemic control deteriorates and treatment requirements escalate.

B. Progressive pancreatic β-cell failure in patients with type 2 diabetes in the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). Beta-cell function was estimated using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) and was already below 50% at the time of diagnosis. Thereafter, long-term incremental increases in fasting plasma glucose were accompanied by progressive β-cell dysfunction. If the slope of this progression is extrapolated, it appears that pancreatic dysfunction may have been developing for many years before diagnosis of diabetes.

B, Adapted from Holman RR. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1998; 40 (Suppl.):S21–S25.

Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MWJ, Hobson RP, Britton R, Davidson LS. Davidsons Principles and Practice of Medicine. 23rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2018.

Epidemiology of Types 1 and 2 DM

The incidence of both Types 1 and 2 DM is increasing worldwide. Chronic complications of DM—which include heart and vascular disease, eye disease that can progress to blindness, kidney failure, and neuropathy—make the condition a major medical and public health concern.

Type 2 DM accounts for most of the increase in diabetes mellitus worldwide, but Type 1 is also increasing at about 3–5% per year. The rise in Type 2 is linked to the epidemic of obesity and other factors such as sedentary lifestyle, while factors causing increased Type1 are not well understood.

In the United States, over 30 million people are estimated to have diabetes with another 25% undiagnosed. The condition of “prediabetes,” defined as “impaired fasting glucose,” carries a high risk for progression to T2 DM. A CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) report in 2017 estimated that up to 34% of US adults have prediabetes.

Certain ethnic groups in the United States are burdened with particularly high rates of diabetes. These include Pima Indians in Arizona, who have a 50% incidence of Type 2 DM. Hispanics, Japanese Americans, and African Americans all have increased risk for Type 2 DM.

Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment are the goals of management. There is strong scientific and clinical evidence showing dramatically improved outcomes when diabetes is diagnosed early and treated aggressively. This means keeping blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible without creating unacceptable hypoglycemia, and controlling hypertension and hypercholesterolemia to achieve levels associated with significant reductions in diabetic complications. Preventing complications is best, but delaying their onset and slowing their progression will also reduce morbidity and mortality. In order to achieve these goals, there needs to be a team approach with nutritional counseling, education, and monitoring. Patients need good medical coverage, and one of the problems people with diabetes are currently facing is inability to pay for insulin. If we could find better ways to help people with Type 2 DM to lose weight, their insulin requirements would drop, lipids would improve, and costs of medication would be less. Improving diabetic care requires not only a team approach, but it also needs to be a public health priority.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus is defined as glucose intolerance (hyperglycemia) that develops during the second or third trimester of pregnancy. Diabetes diagnosed during the first trimester is classified by the American Diabetes Association as pre-existing pregestational diabetes.

During pregnancy, insulin resistance increases, and in order to maintain normal glucose levels, there must be an increase in insulin secretion. If the beta-cells can’t increase their production of insulin, hyperglycemia occurs, resulting in gestational diabetes mellitus. Insulin resistance is most pronounced in the third trimester, and most GDM is diagnosed at this stage of pregnancy. For this reason, screening for GDM is routinely done between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of GDM is related to the prevalence of T2 DM in the population.

-

Table 17-28. Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus.

Maternal age >37 y

Ethnicity

Indian subcontinent: 11-fold

Southeast Asian: 8-fold

Arab/Mediterranean: 6-fold

Afro-Caribbean: 3-fold

Prepregnancy weight >80 kg or BMI >28 kg/m2

Family history of diabetes in first-degree relative

Previous macrosomia/polyhydramnios

Previous unexplained stillbirth

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Source: Greenspan.

Since GDM usually develops late in pregnancy, congenital deformities are not associated with this condition. However, GDM is associated with increased risk for stillbirths and macrosomia (fetal overgrowth). Macrosomia results from maternal hyperglycemia, which causes fetal hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, leading to increased growth (increased fat stores, increased length). If blood glucose levels are well controlled during pregnancy, macrosomia is less likely to occur. Other risks for the newborn include hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, elevated bilirubin levels, and respiratory distress. Children born to women with GDM are at increased risk for T2 DM later in their lives (and also for metabolic syndrome, which will be discussed later in the course).

Most women with GDM recover normal glucose tolerance after delivery but remain at increased risk for later development of T2 DM. For this reason, they should continue to be monitored over time.

Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young

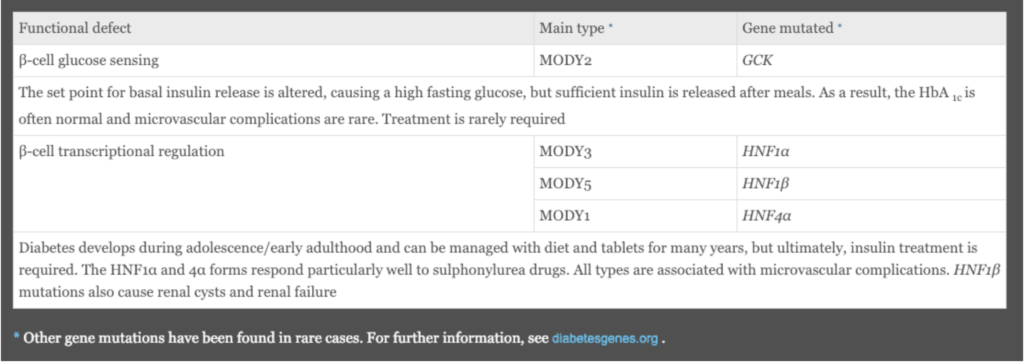

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young, termed MODY, describes a group of individuals with monogenic DM transmitted as an autosomal dominant genetic defect of pancreatic beta-cells. There are numerous MODY subtypes, all reflecting different mutations. As a group, MODY is diagnosed in late childhood and before age 25. The underlying pathophysiology results in partial defects in the release of insulin and patients are not initially prone to diabetic ketoacidosis. The course of the diabetes and prognosis differ depending upon the mutation.

Box 20.10. Monogenic diabetes mellitus: maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY). Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MWJ, Hobson RP, Britton R, Davidson LS. Davidsons Principles and Practice of Medicine. 23rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2018.

The above table lists the most common types of MODY. MODY 2 is important to recognize because the GCK (glucokinase) gene mutation alters the set point for beta-cell release of insulin, and mild hyperglycemia characterizes MODY 2. It is associated with a benign course and typically doesn’t require treatment. Microvascular complications are rare.

MODY types 1, 3, and 5 are all due to HNF (hepatocyte nuclear factor) gene mutations and are present in adolescence or early adulthood, as is typical of MODY. Clinical management early in the course includes diet and sulfonylurea medication, but patients eventually require insulin and are at risk for microvascular complications.

MODY patients do not have an increased incidence of overweight or obesity, as is seen in patients with T2 DM, and they are not insulin resistant.

-

Mutations in the Subunits of the ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channel

Two rare dominant activating mutations occur in the beta-cell channels SUR1 and Kirk 6.2. The channels remain in the open position so that glucose-dependent depolarization is blocked and insulin secretion doesn’t occur. This disorder is discussed again in a later session.

From a clinical standpoint, you should be aware that monogenic forms of diabetes exist, and clues would be age of onset, absence of ketoacidosis (except in some cases late in the course of the disease), and autosomal dominant inheritance. If one parent has DM, and half of the children have DM, and half of the children in the parent’s family are diabetic, you should suspect monogenic diabetes mellitus, especially MODY.

Neonatal Diabetes

Neonatal diabetes occurs in the first 6 months of life. Affected infants demonstrate hyperglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis and are severely insulin deficient. About half go into remission by 12 to 18 months but recur in adolescence or early adulthood. Diabetes is permanent in the other half. It turns out that about 2/3 of those with permanent neonatal DM have an activating mutation that causes the K-ATP channel not to respond to the rise in ATP generated by oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate oxidation so the channel remains open with the result that beta-cells don’t secrete insulin. The clinical significance here is that sulfonylurea drugs close the K-ATP channel, which depolarizes the membrane so calcium flux occurs with resulting insulin secretion. These patients can therefore be treated with sulfonylureas with good glucose control.

Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

Criteria for diagnosing DM have evolved over time and will likely continue to do so. Hyperglycemia is the pathognomonic feature. Hyperglycemia can be the end result of a variety of disorders of glucose homeostasis.

A clearly elevated glucose level—for example, a random glucose of 250 mg/dL—or two glucose levels greater than 200 mg/dL and associated with symptoms of DM are considered diagnostic. However, there is no sharp physiologic cutoff point in the normal population.

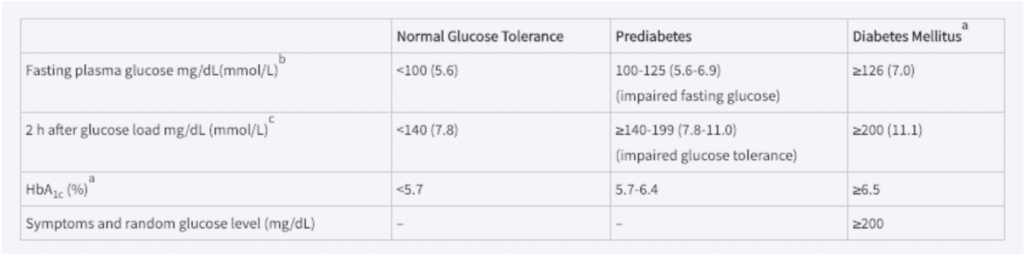

Table 17–11. Criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes.

A. A fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c is diagnostic of diabetes if confirmed by repeat testing. HbA1c test should be performed using an assay certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization program and standardized to the DCCT assay.

B. A fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL is diagnostic of diabetes if confirmed on a subsequent day to be in the diabetic range after an overnight fast.

C. Give 75 g of glucose dissolved in 300 mL of water after an overnight fast in subjects who have been receiving at least 150 to 200 g of carbohydrate daily for 3 days before the test. In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, the result should be confirmed by repeat testing.

Gardner DG, Greenspan FS, Shoback DM. Greenspans Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. 10th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education; 2018.

Current guidelines use fasting plasma glucoses greater than 126 mg/dL as diagnostic of DM, or an abnormal glucose tolerance test as follows:

-

- Draw baseline glucose.

- Give 75mg glucose po (by mouth).

- Check glucose level 2 hours later.

If 2-hour glucose greater than 200mg/dL, DM is diagnosed. If between 140 and 200 mg/dL, impaired glucose tolerance is diagnosed.

A fasting BG between 100 and 125 mm/dL is also considered diagnostic of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT).

People with IGT are at increased risk for developing DM over time, and there is a great deal of interest in identifying this group to find interventions which prevent progression to DM. Studies have shown that people who remain in the IGT category won’t develop diabetic eye disease or nephropathy, but they are at increased risk for heart disease and stroke.

Fasting glucose levels (12- to 14-hour fast) are emphasized more than the glucose challenge test in recent guidelines. HgbA1c, a fraction of blood hemoglobin that is nonenzymatically glycosylated depending on ambient blood glucose levels, has also been used to diagnose DM. There are problems with using this test because the average glucose level indicated by a given level of HgbA1c varies among individuals, and a number of factors can affect the reliability of the test, including red cell lifespan, Hgb variants, vitamins C and E, and other factors. There is also considerable variation within the same individual. Nevertheless, HgbA1c has been very useful for population studies of diabetics and shows good correlation with risk for diabetic complications. HgbA1c is a useful tool for assessing diabetic patients who don’t do home glucose monitoring and also for providing an index of a person’s glucose control over time.

Hg A1C

HgA1c is a form of glycated hemoglobin that is measured to assess average blood glucose levels during the previous 2 to 3 months. Glycated hemoglobin results from a nonenzymatic ketoamine reaction where hemoglobin is chemically linked to monosaccharides, including glucose, galactose, and fructose. The reaction occurs between free amino groups on the alpha and beta chains of hemoglobin. It turns out that glycation of the N-terminal valine of the beta chain is the only reaction that gives the hemoglobin molecule enough negative charge to be separated from other hemoglobins in charge-based assays. These hemoglobins are called HgA1. The HgA1c fraction specifically reflects glucose levels and is the largest fraction of the HgA1 group. Once the reaction occurs, it is irreversible for the rest of the red cell’s lifespan. A linear relationship exists between average blood glucose levels and the HgA1c value. For this reason, HgA1c is useful for assessment of glucose control over a period of 2 to 3 months. Measurement of HgA1c in large populations has been used to determine at what level of HbA1c (and the corresponding average glucose level) microvascular complications of diabetes begin to occur. Micro- and macrovascular complications will be discussed in detail in a later session. Microvascular complications include retinopathy, glomerulopathy, and nerve damage. Patients with DM can be checked at 3- to 4-month intervals to assess average glucose control. This information is helpful in patients who don’t do home glucose monitoring and can be used in conjunction with home glucose measurements in the patient’s management.

The equation used to convert HgA1c to average glucose level is as follows:

(28.7 x HgA1c) – 46.7

There are several potential problems with the HgA1c measurement that the physician should be aware of. The interpretation is based on an average red blood cell lifespan of about 120 days. You can see how someone with a shortened RBC lifespan would have an artifactually low HgA1c, because the red cells would have less time to become glycated and the percent of HbA1c would be lower. This would be misleading, indicating lower average glucose levels than were actually present. Some Hg variants will interfere with glycation and give unreliable results. Some Hg anomalies interfere depending on the assay used. Finally, in the same person, the HgA1c will vary for a given average glucose level.

The use of HgA1c for the diagnosis of DM has been somewhat controversial because of the variation within and among normal individuals. The American Diabetes Association has given a HgA1c value of 6.5% as the cutoff for the diagnosis of DM. This value was chosen because as HgA1c rises above 6.5%, the risk for diabetic retinopathy and other microvascular complications rises. (Microvascular complications correlate with degree of hyperglycemia.) People with HbA1c levels between 5.7 and 6.4% are considered at high risk for developing T2DM, and people in this range can be considered “pre diabetic.”

In practice, a combination of fasting glucose or a glucose tolerance test in conjunction with HgA1c are generally obtained. Patients with established DM may have HbA1c checks at 3- to 4-month intervals, or less frequently if they are very stable, and fingerstick blood glucoses as needed to maintain good control and guide insulin dosing.

Type 1 DM is usually readily diagnosed because insulin deficiency causes acute symptoms starting with increased thirst and urination and progressing to diabetic ketoacidosis. As noted, Type 1 DM typically presents in childhood or adolescence. The more indolent form, latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA), can be mistaken for Type 2 because it occurs later in life and evolves more slowly due to a less aggressive autoimmune process. Clues are normal body weight and fat distribution, poor or no response to oral agents, a rise in glucose despite weight loss, careful diet, and exercise. Most Type 1 diabetics don’t have a positive family history.

Type 2 DM can be asymptomatic for years and some of the symptoms—such as recurrent vaginal candida infections in women or mild peripheral neuropathy, with decreased sensation in the feet and paresthesias (pins and needles)—may not be recognized as DM complications. Many Type 2 diabetics are undiagnosed until they develop complications such as retinal changes on opththalmologic exam or proteinuria on urinalysis. Overweight is common in Type 2 DM, along with a pattern of central weight gain. Most Type 2 diabetics have relatives with this condition. The diagnostic criteria given above are primarily for Type 2 diabetics, since Type 1 diabetics are overtly hyperglycemic.