Writing case reports: A balanced perspective

As educators, we often encounter students eager to write case reports. Dr. Coidado fielded so many queries and requests for assistance that she reached out to me to help her create this resource.

While I have many reservations about this effort and my own personal biases, it’s important that I present you a balanced view of the pros and cons.

-

Pros

- Cons

- Showcase rare events: Case reports often highlight medical “zebras”—rare and unique cases that can be fascinating to explore.

- Learning experience: The process of writing a case report can be an engaging and educational experience. It requires a deep dive into the patient’s unique aspects and a mastery of the existing literature.

- Sub-specialty collaboration: Working with various specialties to get the images and captions just right enhances your education as a clinician.

- Presentation preparation: The work which was needed for me to write and see to publication the case reports I have used as examples in this guide taught me skills which came in very handy. For example, when I was a chief resident, there were many occasions where I had to present cases at the podium during conferences. As an attending surgeon, I often participate in “Indications Conference” (pre-op conference) or “M&M” (morbidity and mortality conference). Knowing exactly how to take listeners through the patient’s journey via a visual presentation with a narrative arc is a valuable skill.

- Publication benefits: Publishing rare conditions can be beneficial for the medical community. Future encounters with similar cases may benefit from your detailed documentation of the patient’s presentation, diagnostic work-up, management, and outcome.

- Patient/family rapport: Sharing the published work with the patient and their family can be a deeply rewarding experience. They often find it fascinating and gratifying that their condition has been documented for others to learn from. This effort not only enhances their respect for you but also shows your commitment to turning their ordeal into a meritorious academic contribution.

- Residency application misconceptions: Many students believe that a long list of publications is essential for a strong residency application. However, the ERAS (Electronic Residency Application Service) only allows PubMed-indexed publications to be listed in a specific section. There is a separate section for non-PMID publications. Anything can be listed in this section, even patient-facing education brochures, webpages, works-in-progress, etc. I often advise students to fully avail themselves of this section of the ERAS CV and not to feel uneasy if their PMID section is thin. It takes years to publish truly good scientific work, and no one expects a full-time medical student to have this kind of time for the scientific process. The notable exception is for those in MD/PhD programs.

- Application padding: Program Directors (PD) have wised up to the tactics that students are using, now that USMLE is pass/fail. Many PDs see a high number of CV listings as padding. This is a recent quote from a surgery PD at an academic program:

We’ve cut down the number of interviews we do from 100 to 80 per season. We received almost 700 application last year—a number that has grown due to the adoption of virtual interviews. Most medical schools no longer provide class rank, and there is no Step 1 score to help differentiate the academic abilities of the applicants. We rely heavily on program signaling, geographic signaling, and traits that show a strong interest in working with underserved populations or in safety net hospitals. We spend a lot of time poring over students’ extra-curricular activities and personal statements looking for clues that would indicate those types of interests. We de-prioritize research since almost all applicants have some type of research in their portfolio.

- Perceived ease: While case reports may seem like low-hanging fruit, the reality is that it will take you about a year of effort. You may need to apply for an exempt IRB from the institution where the patient received care. The IRB will want to verify that no patient-identifying information will be used. They will wish to learn how you plan to safeguard and ultimately destroy patient data. You may need to verify that the consent forms of the institution included use of photography or medical imagery for purposes of academic publication. If it did not, then you may need to write a special consent for the patient/family to sign which acknowledges the use of their information. Receiving adequate supervision from your preceptor may be a challenge since they have moved on to the pressing needs of the patients now in front of them.

- Publication fees: Many journals charge fees for publishing case reports, which can be a tremendous financial burden for students. Some fees are $2K+. Many faculty at WSU COM see this pay-to-publish model as predatory. We frown upon journals which take advantage of students’ desperation to appear successful on paper.

Some examples of journals accepting case reports

American College of Surgeons Case Reviews in Surgery

- Peer-reviewed

- Indexed in PubMed

Journal of Case Reports and Images in Surgery

- Peer-reviewed

- Indexed in PubMed

Journal of Education and Teaching in Emergency Medicine

- Peer-reviewed

- Indexed in PMC

Dr. Coidado organized a workshop led by peers. Go to the Writing Case Reports page to view the slides and watch a video of the discussion.

In conclusion . . .

Before embarking on writing a case report, please ensure you are doing it for the right reasons. Instead of being overly focused on a publication that may require a significant financial investment, consider presenting at a conference that specializes in case reports.

An example of one is the annual meeting of the Seattle Surgical Society. This event, held on the first Friday in February, offers a great opportunity to present your work at the podium, even though it is not associated with journal publication. Click here to peruse the 2025 program.

Another option for surgical case reports is to publish on the operative nuances in the “How I do it” section of a journal. “Technical notes” are brief articles focused on a new technique, method, or procedure. These should describe important modifications or unique applications for the described method.

Lastly, if your goal is for a PMID, letters to the editor are often indexed in PubMed. If you read something published recently which reminds you of your case, you could write a letter to the editor which describes your case. If it is picked up by the journal, it is unlikely to require a fee.

another pro tip

Any time you publish, you will be offered the option to pay a fee for open access or color reprints.

Declining both will save your budget. The electronic version of the publication is usually in color without the additional fee. Open access is important for research which will benefit the lay public to read (i.e., a scientific discovery appropriate for mainstream media publicity).

The experience of preparing and presenting a case report can be rewarding and educational. Remember, it’s the process, not the product. To aid you in your process, Ariane Smith from our fantastic Digital Publishing team and I present you this resource called “Anatomy of a Case Report.” We have used several examples of case reports to call out common features.

As you work on your case report draft, you could start bookmarking these elements for your case write up from your patient’s medical record.

No PHI

Remember to keep NO PATIENT IDENTIFYING INFORMATION on your WSU devices or on clouds. Before embarking, remember that you must have the patient’s and health care system’s permission to do so.

If you have case reports that you have published and would like to be featured here for other students to learn from, please contact us!

We wish you the best in your scholarly journey.

Most sincerely,

Dr. Anjali Kumar (content contributor), Ariane Smith, and Dr. Olivia Coidado

Anatomy of a case report

Case report checklist

(Tap to enlarge; use the arrows to scroll through each example.)

Introduction: A general statement about the disease or condition

The reason: Why is this important? Why take the time to write this up? Why should clinicians read this?

- Is it a clinical conundrum?

- Is the management unknown or controversial?

- Is the condition rare or under-reported?

Patient presentation

Diagnostic work-up

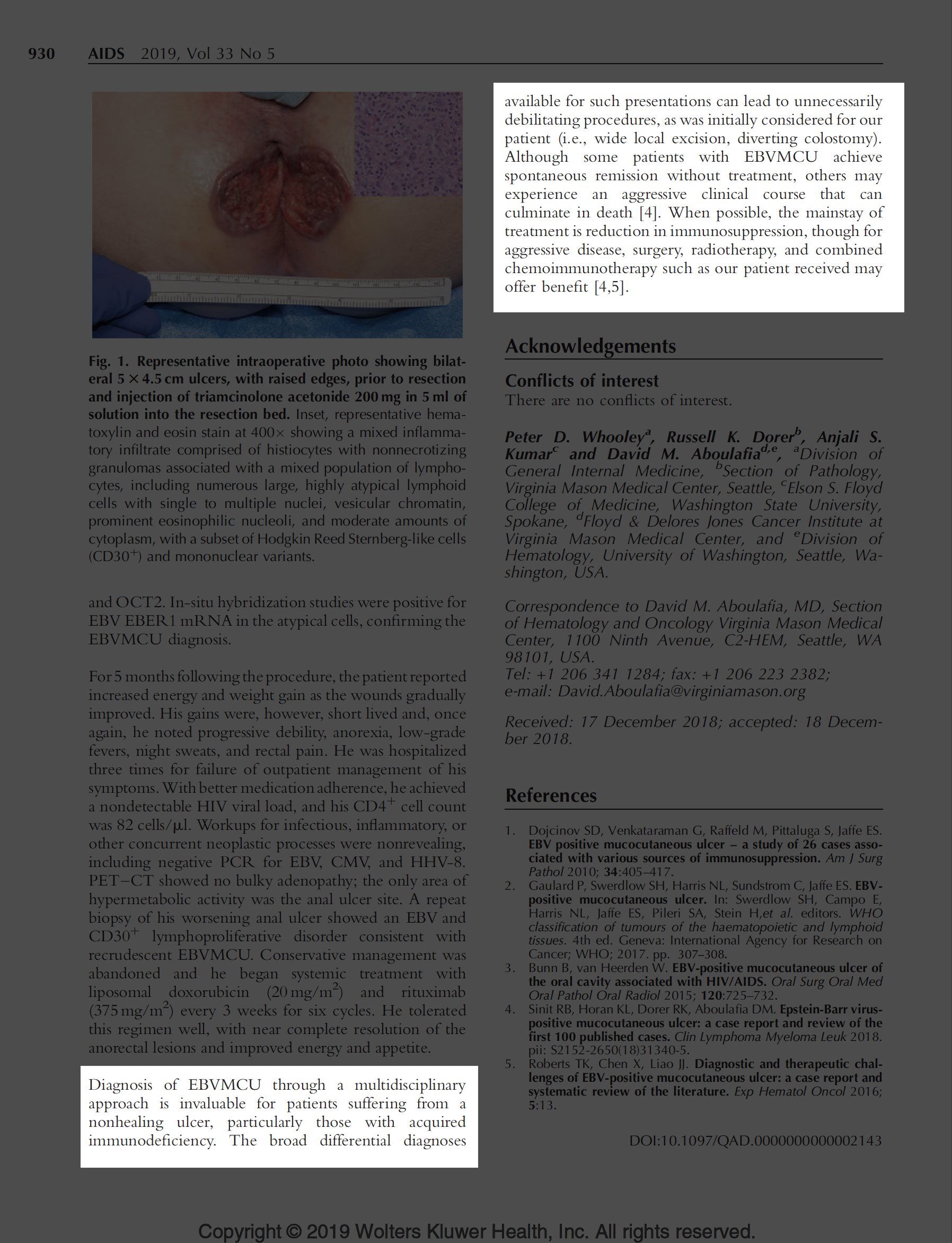

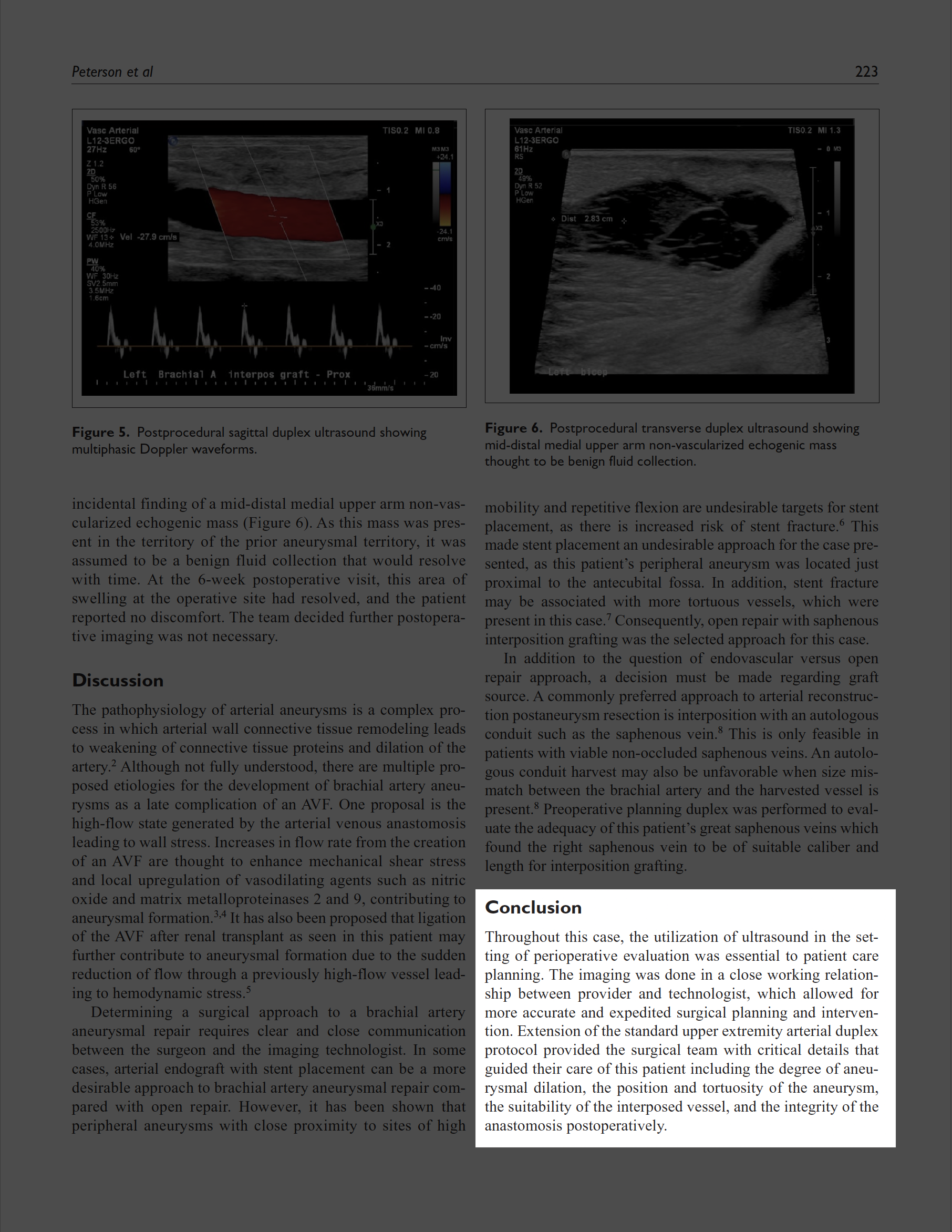

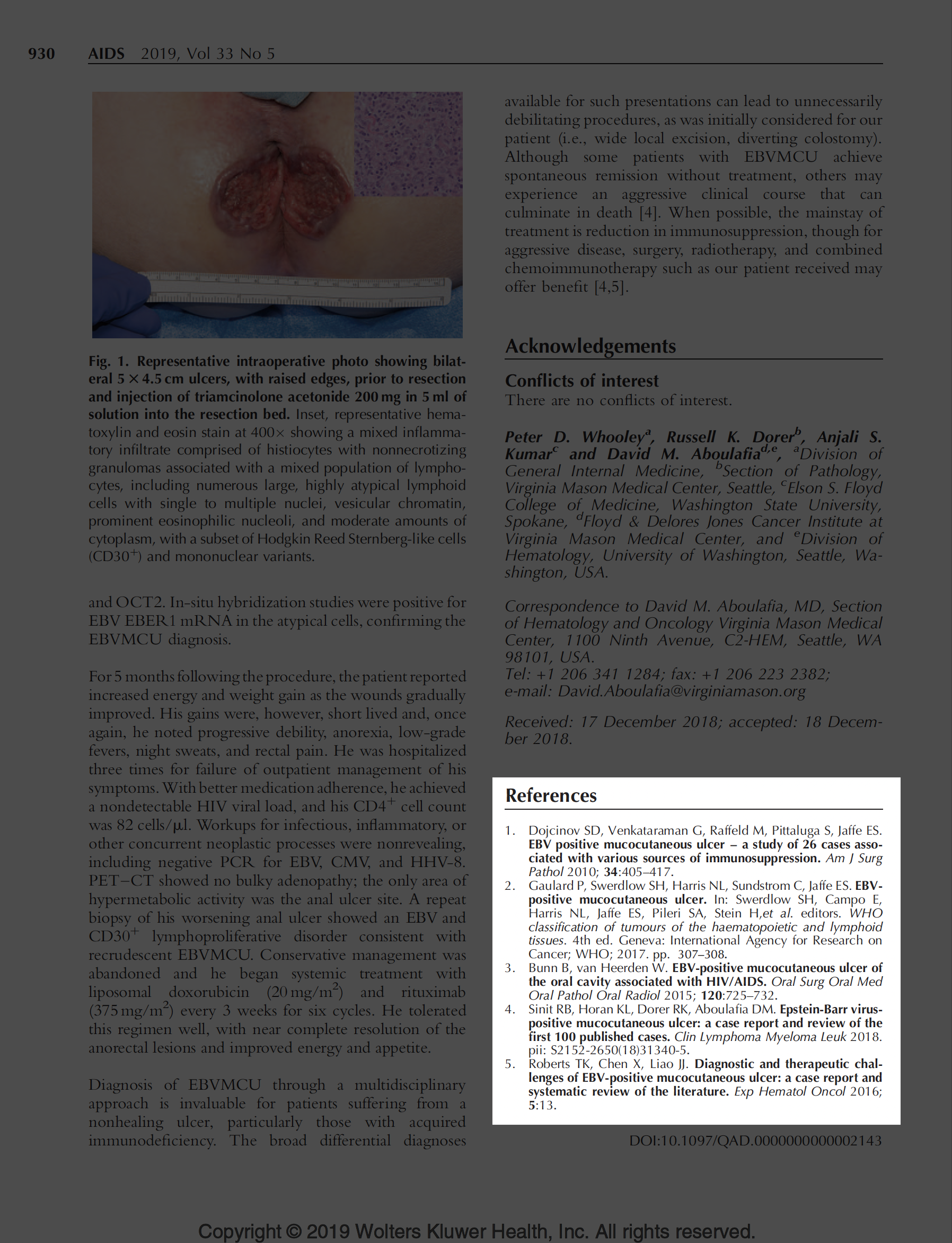

Figures (usually photos)

- In situ (inpatient / operative or outpatient)

- Ex vivo

- Pre-, intra-, or post- (intervention or therapy)

- Radiographs

- Microscopic appearance

- Digital illustrations (consider drawings or algorithms)

Patient outcome

Concluding remarks

References (ideal if <10)

Example articles

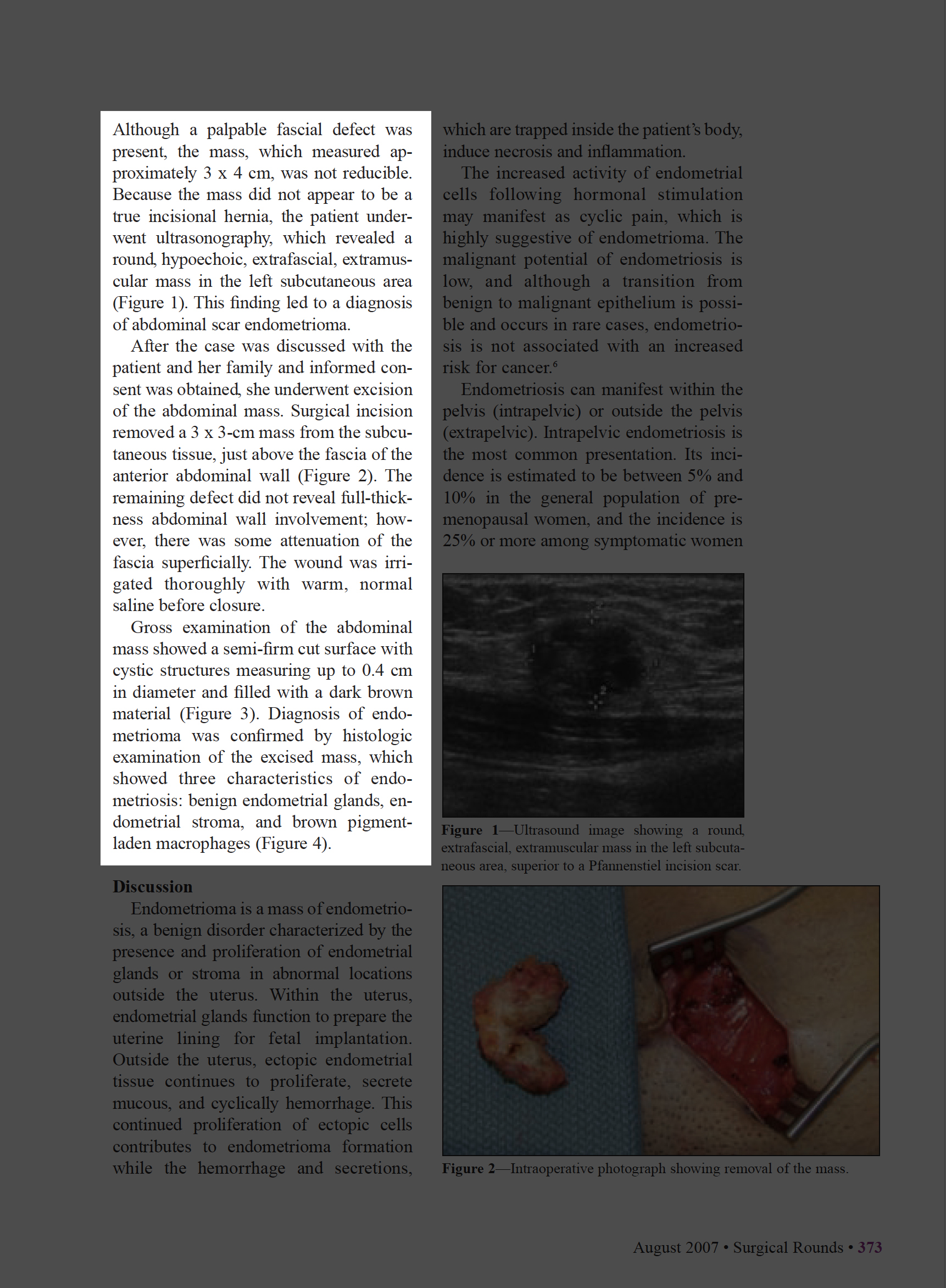

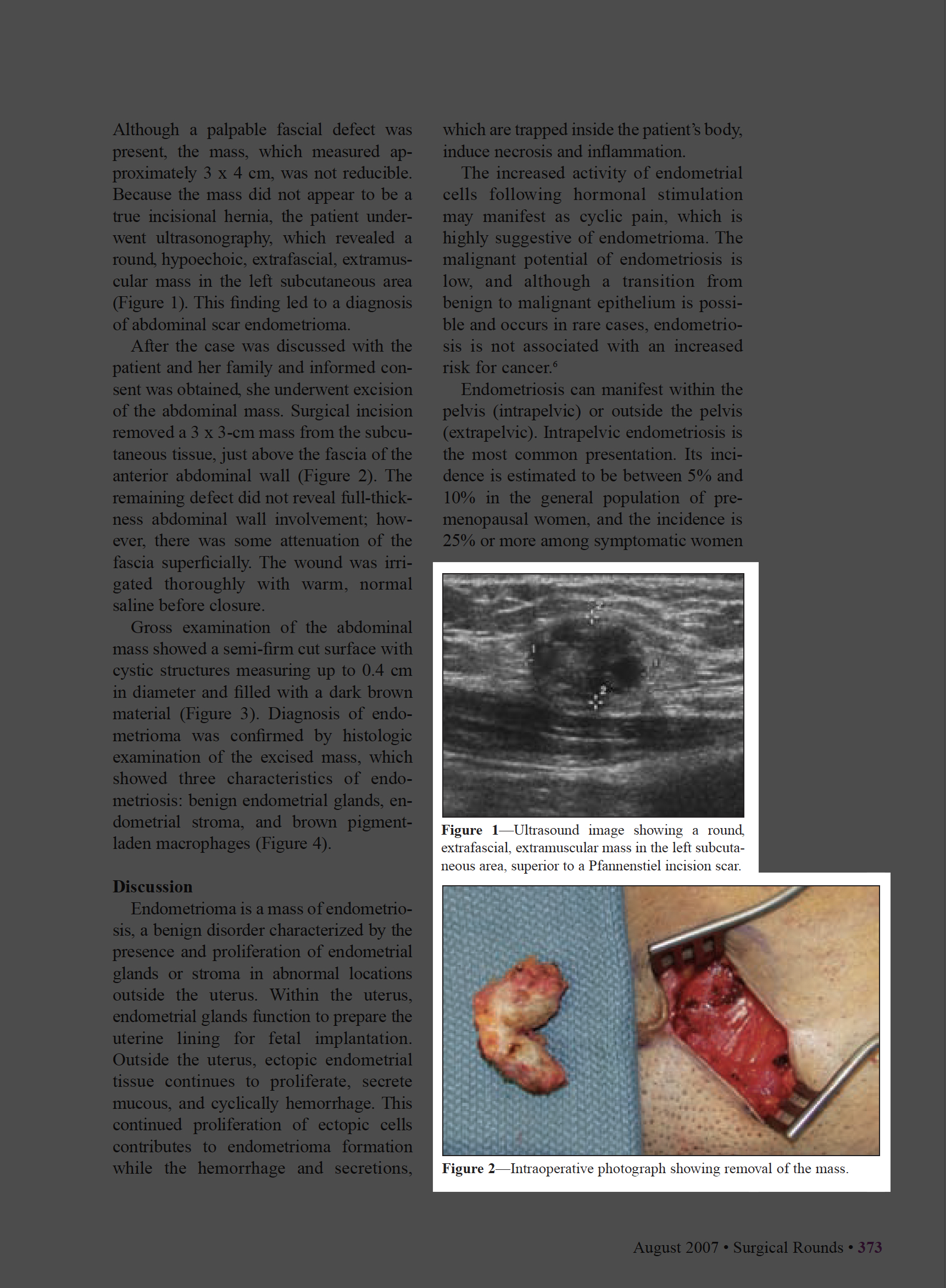

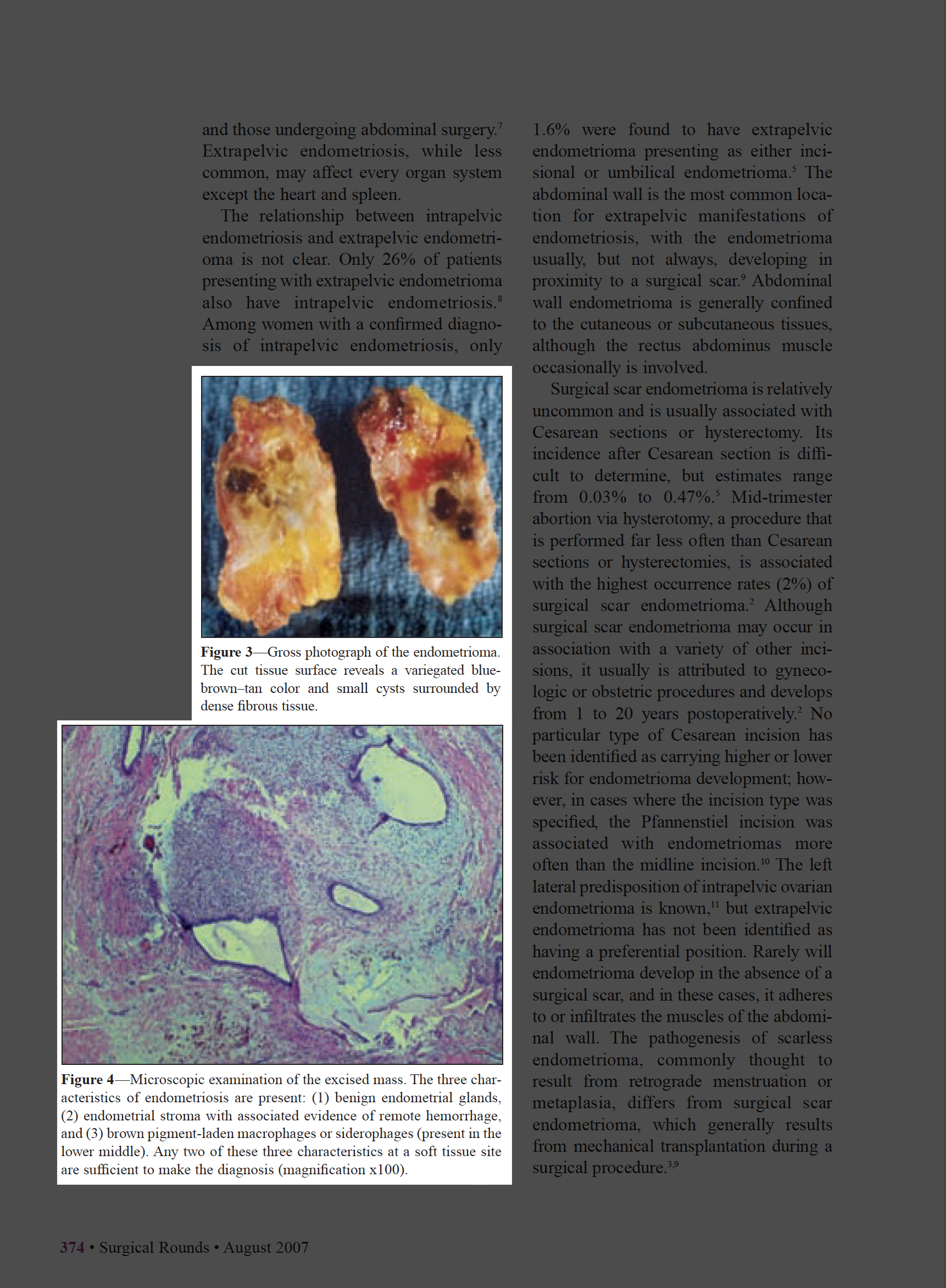

Garwood E, Kumar A, Moes G, Svahn J. Abdominal scar endometrioma mimicking incisional hernia. Surgical Rounds. 2007 August: 372–376.

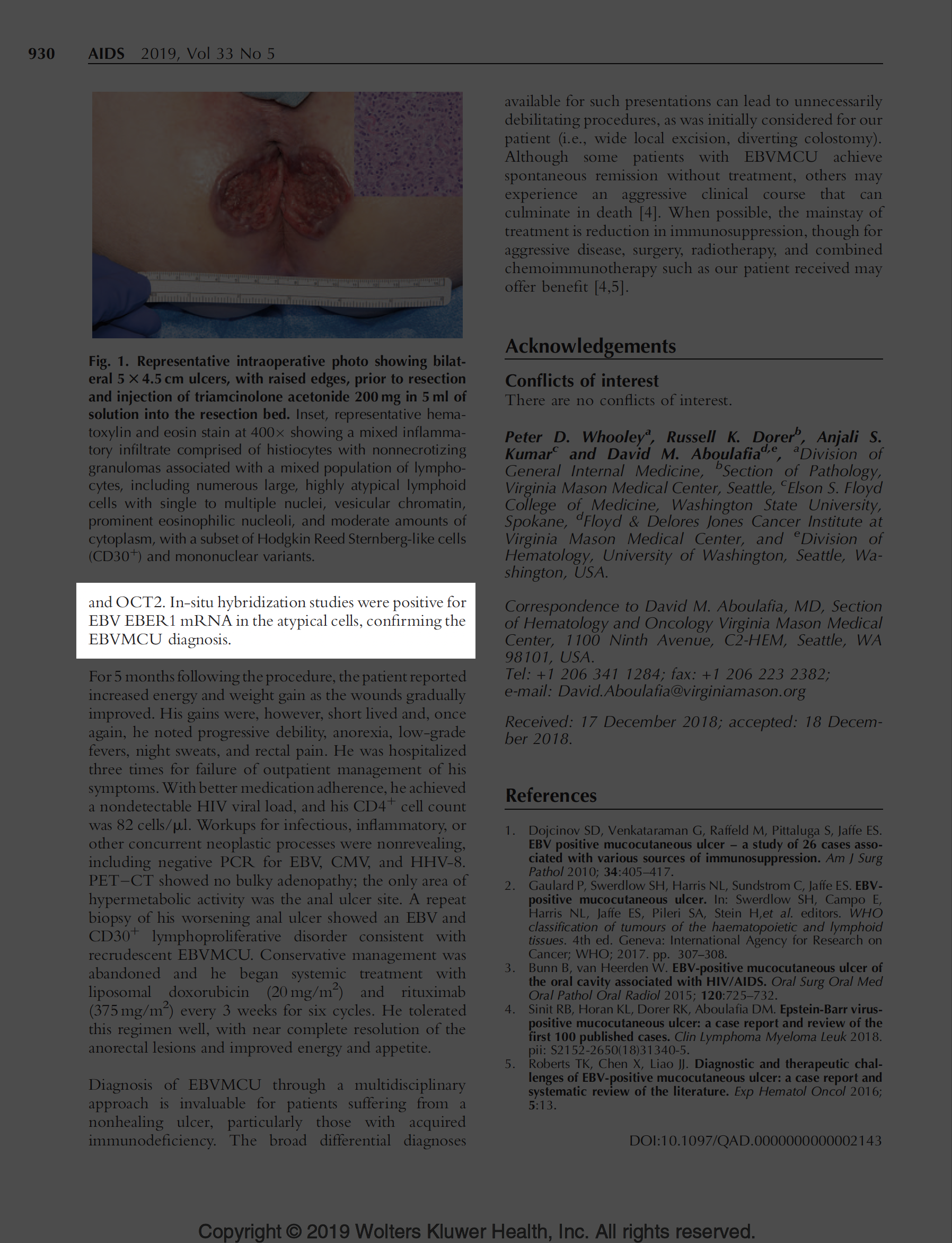

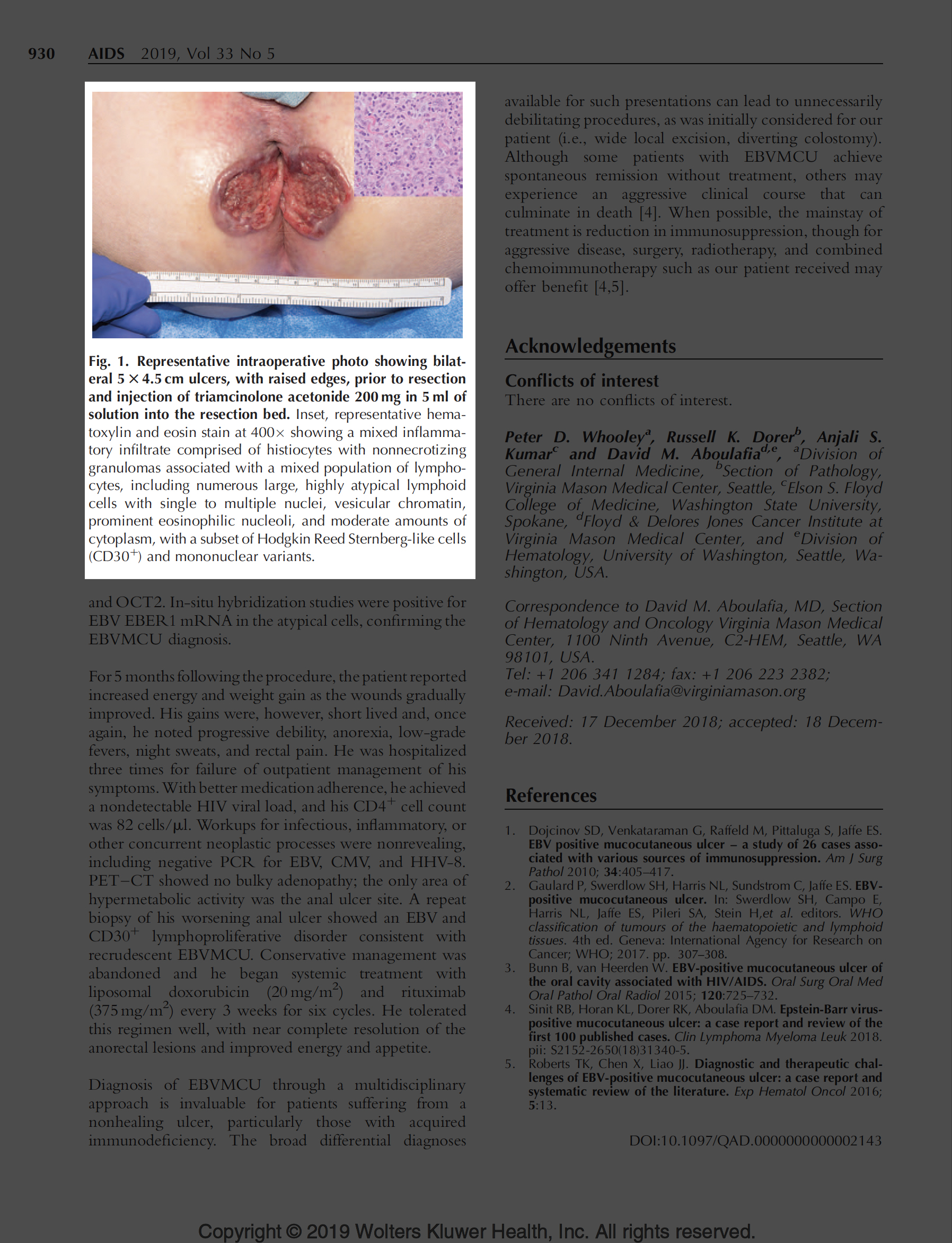

Whooley PD, Dorer RK, Kumar AS, Aboulafia DM. HIV-associated anorectal Epstein-Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer successfully treated with liposomal doxorubicin and rituximab. AIDS. 2019 Apr 1;33(5):929–930. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002143. PMID: 30882496.

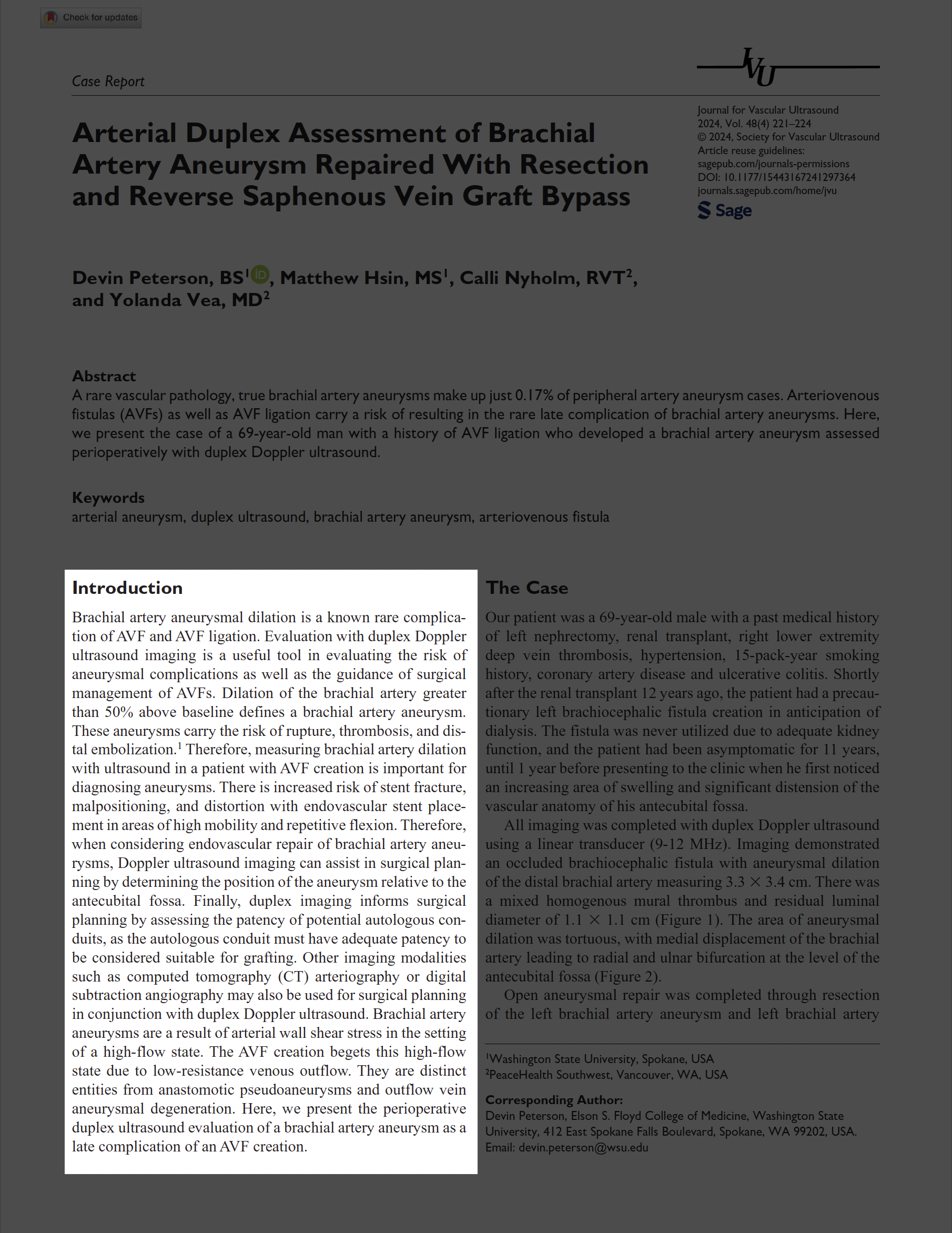

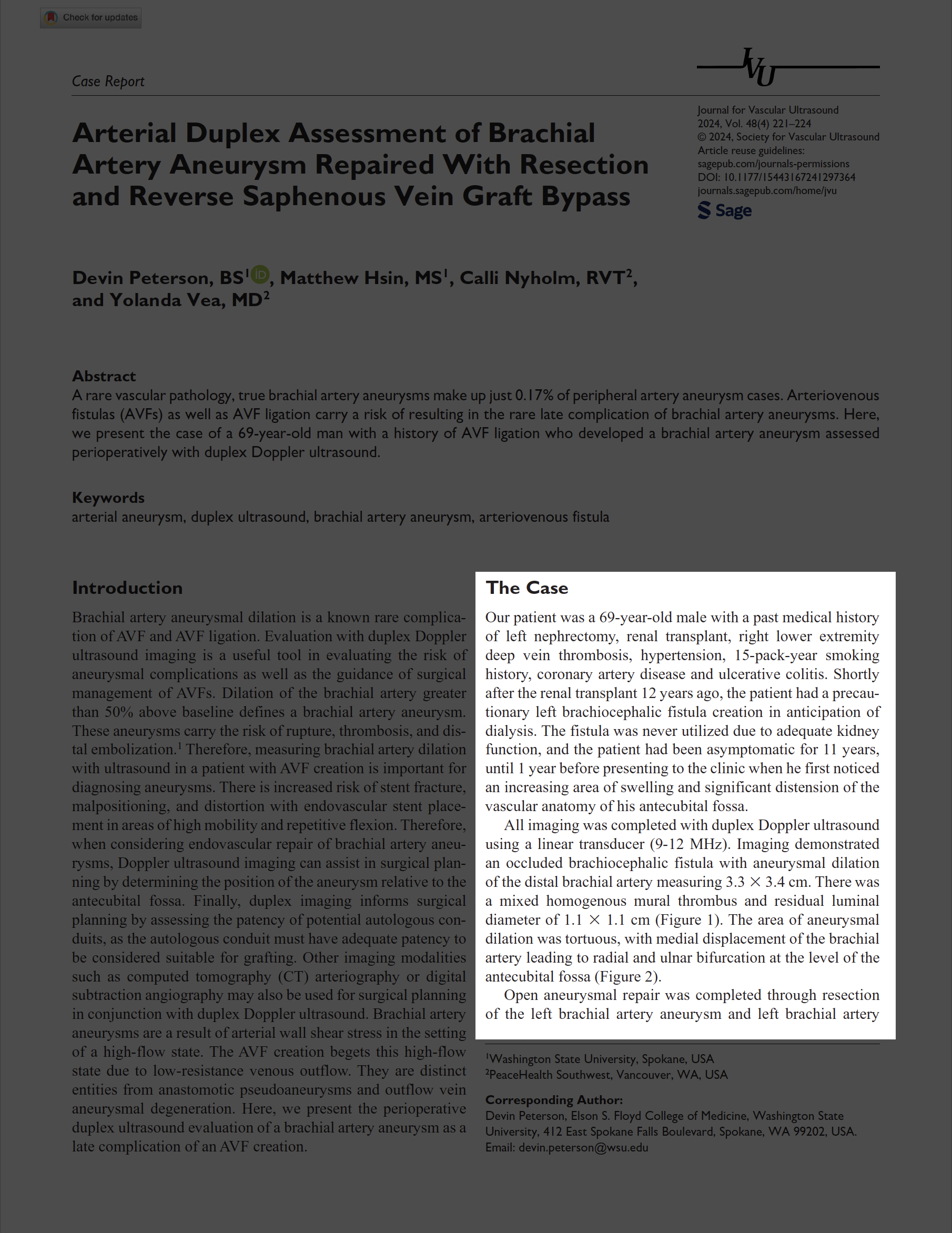

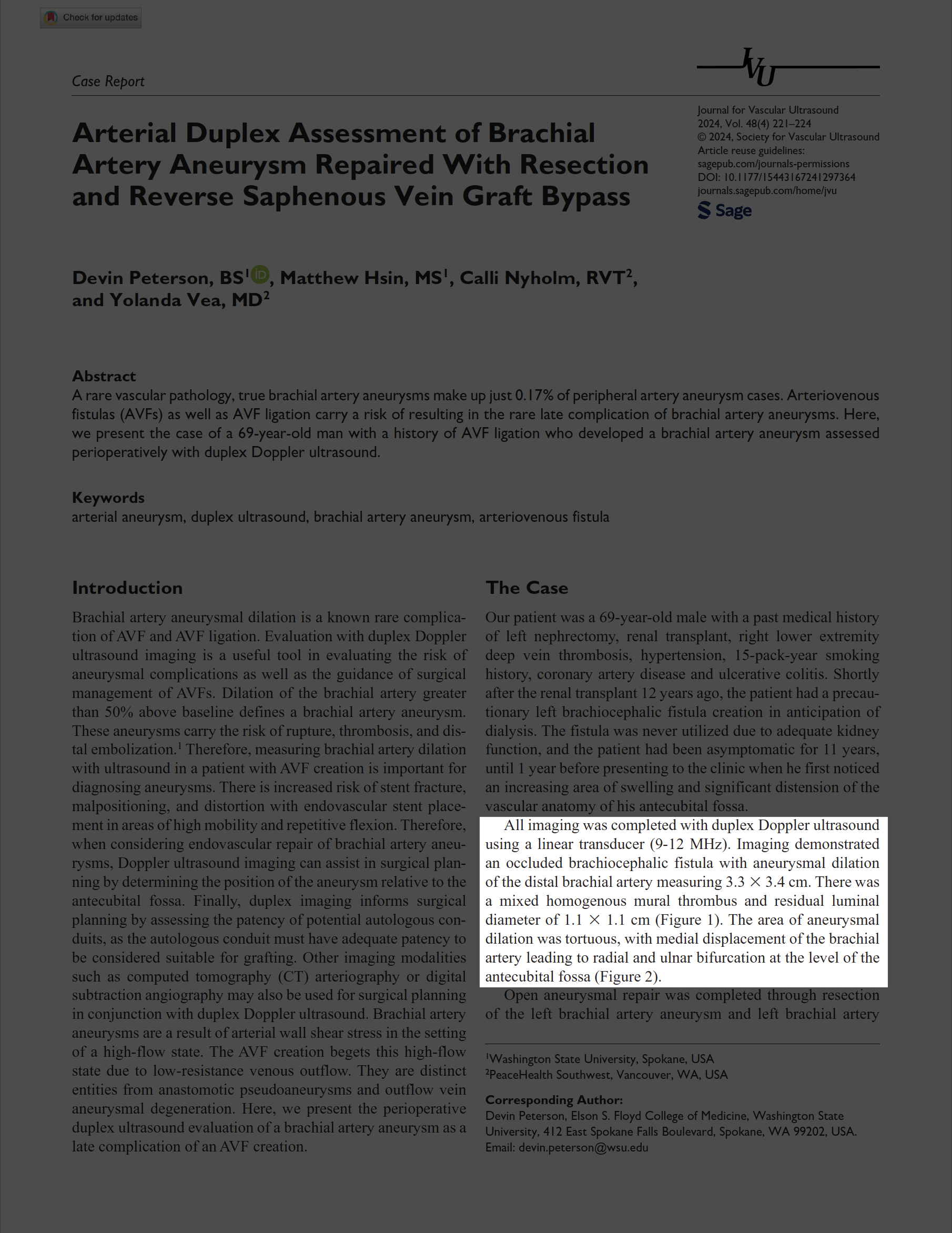

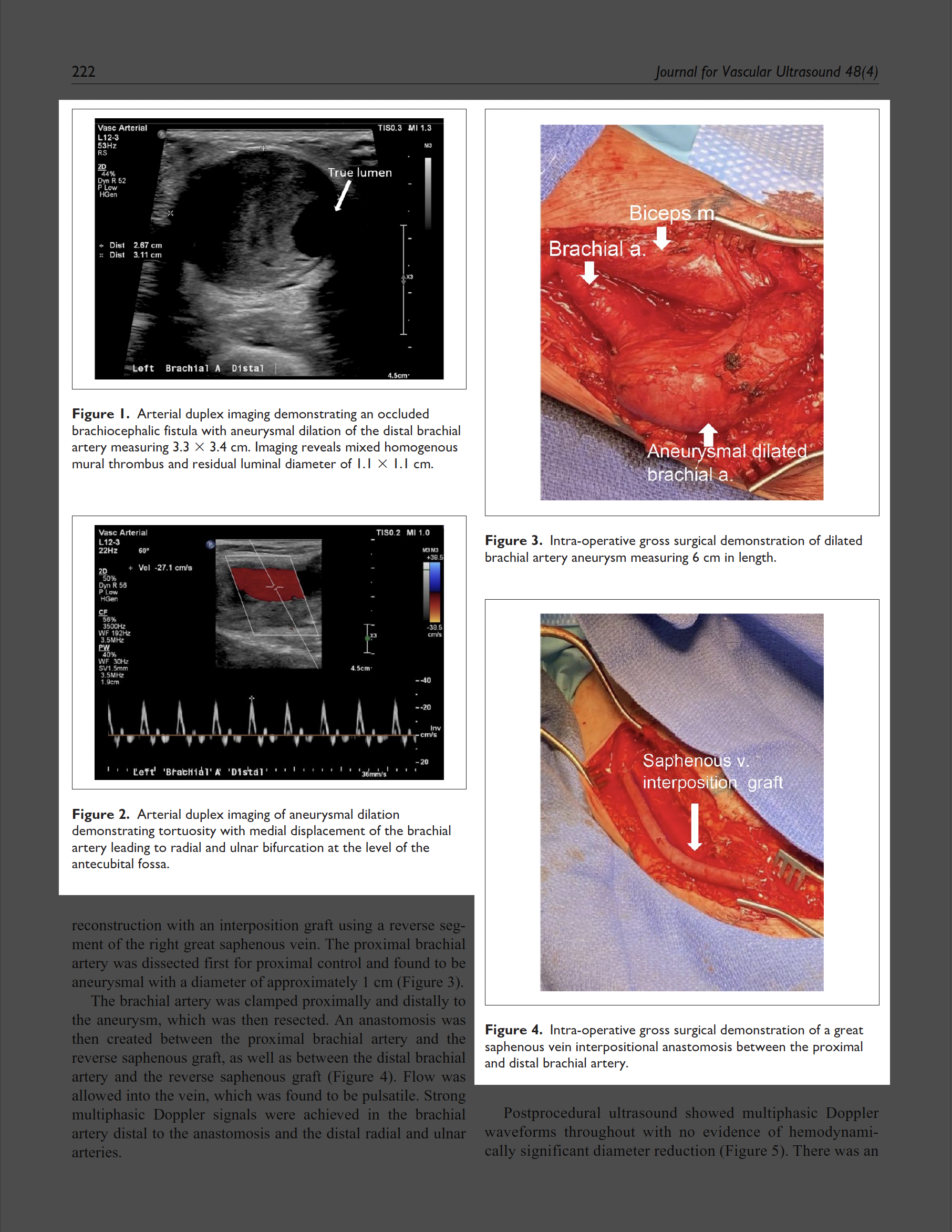

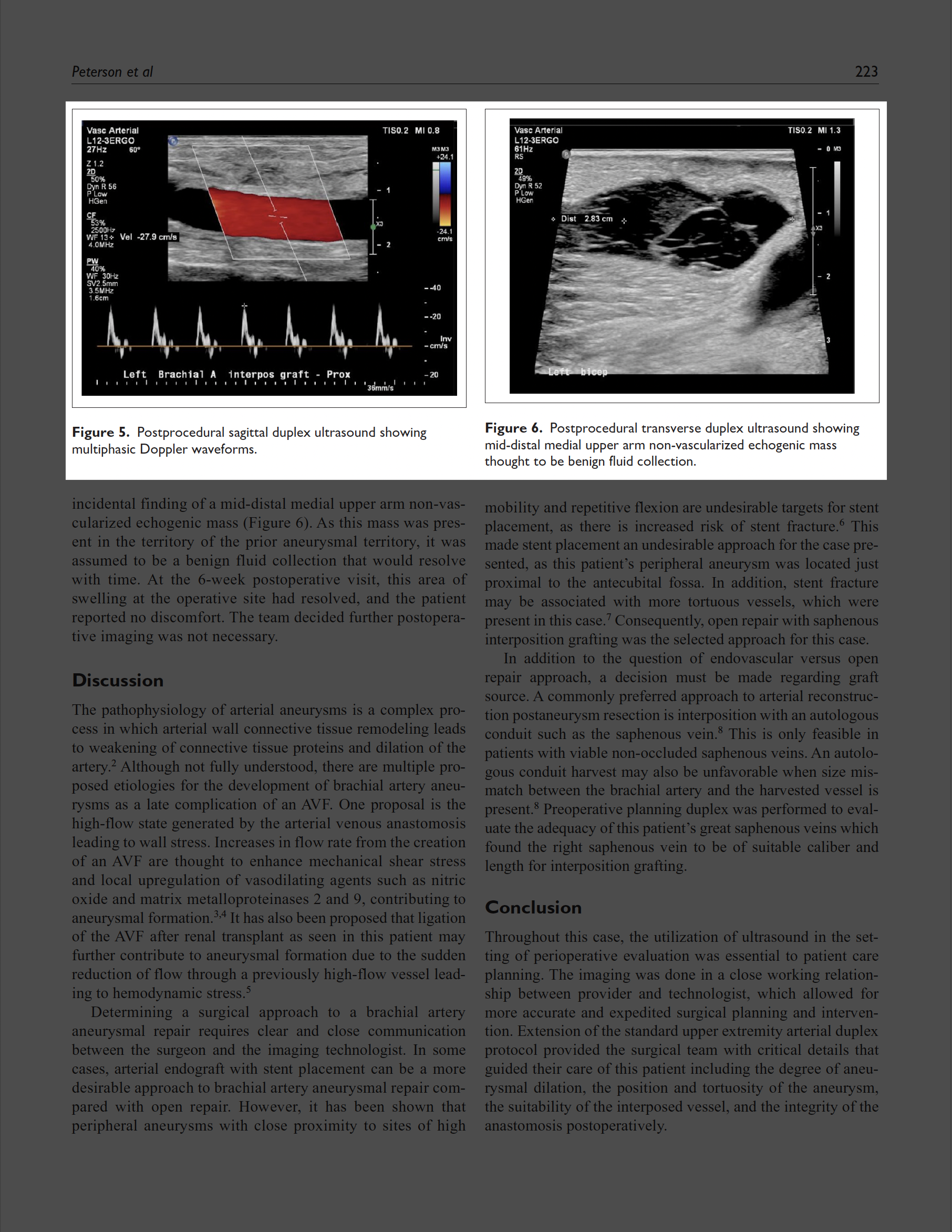

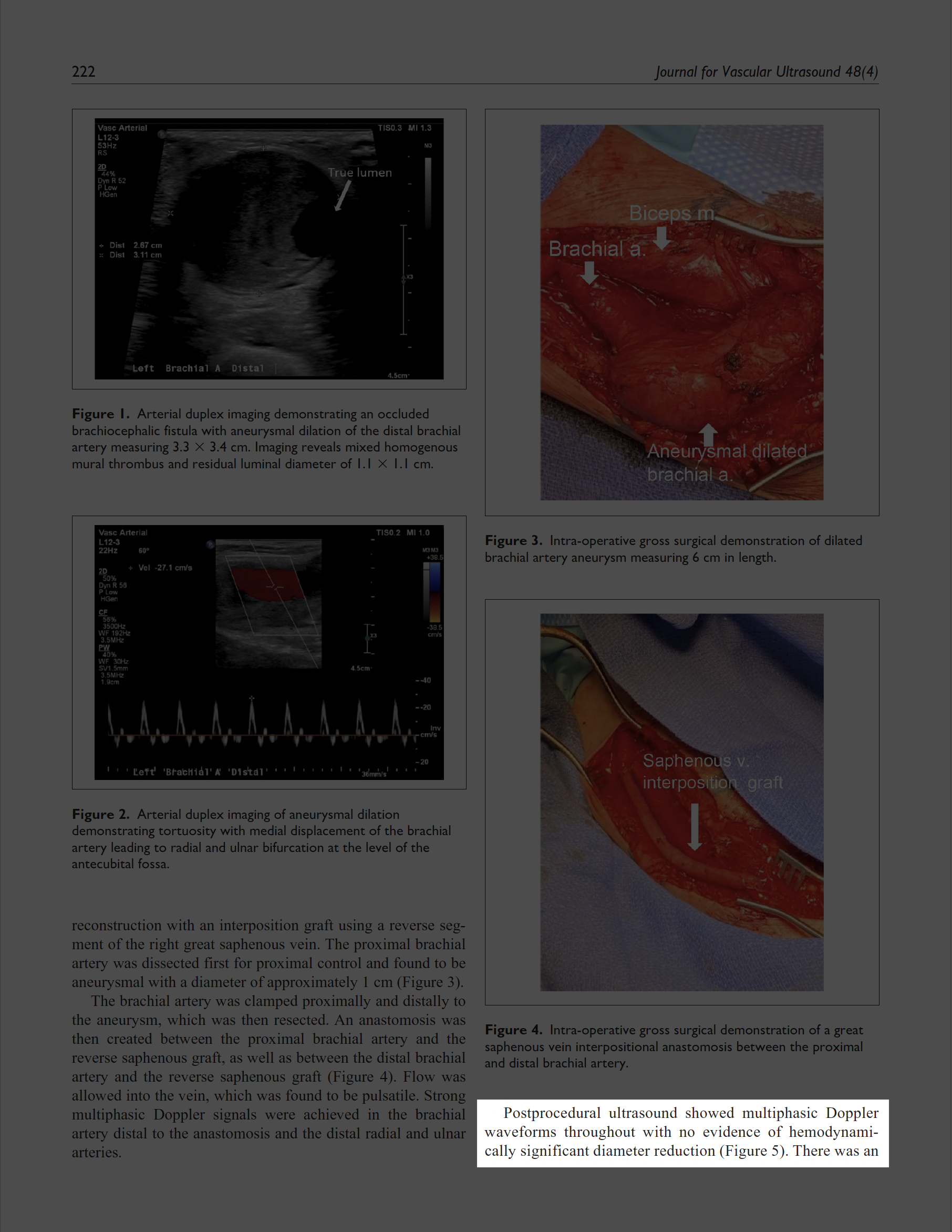

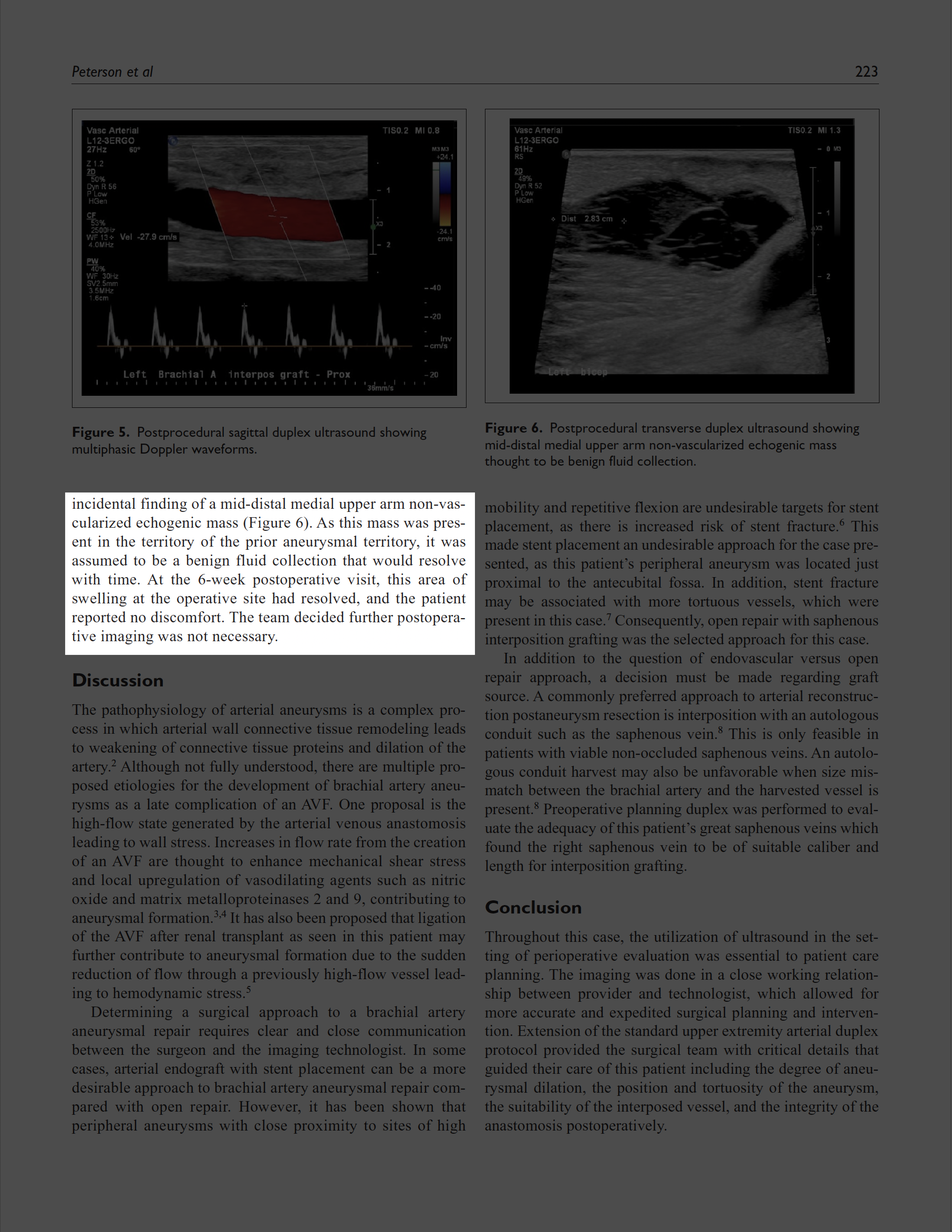

Peterson D, Hsin M, Nyholm C, Vea Y. Arterial duplex assessment of brachial artery aneurysm repaired with resection and reverse saphenous vein graft bypass. Journal for Vascular Ultrasound. 2024, vol. 48(4):221–224. doi: 10.1177/15443167241297364