Gram-negative cocci (GNCs): Diplococci

Neisseria

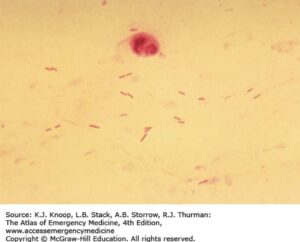

Small intracellular gram-negative diplococci.

Neisseria meningitidis is gram-negative diplococci that colonizes human nasopharynx. It is encapsulated, which distinguishes it from other Neisseria spp and provides an anti-phagocytic protection. After colonizing nasopharynx, organism can evade immune response and reach meninges via bloodstream. Patients with terminal complement deficiency are highly susceptible to N. meningitidis infections. N. meningitidis is a major cause of community-acquired meningitis in adolescents and young adults. Clinical manifestations include meningitis alone, meningococcemia/sepsis, or both—all of which are considered medical emergencies. Meningococcemia is a rapidly progressive infection characterized by septic shock and DIC, which manifests as petechial-purpuric skin eruption. Degree of disease is mediated by lipooligosaccharide (endotoxin) in the bacterial cell wall. Polysaccharide conjugant vaccine for serotypes A,C,Y,W-135 is recommended for all children age 11–18. Protein vaccine for serotype B is available for at-risk persons. Most are susceptible to penicillin, but empiric treatment is with 3rd-generation cephalosporin until susceptibility is proven.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a fastidious gram-negative intracellular diplococci that can colonize the human genital tract and is transmitted via exposure to genital secretions (sexual activity or to neonates in birth canal). It is more fastidious than other Neisseria, requiring enriched media. For this reason, nucleic acid amplification testing is commonly used for diagnostics. Organism causes local invasion of mucous membranes leading to urethritis, vaginitis, and cervicitis/PID. In the neonate, purulent conjunctivitis can occur. Bacteremia can occur, causing disseminated disease characterized by fever and migratory arthritis, with or without skin eruptions. Endotoxin of N. gonorrhea causes less cytokine response compared to N. meningitidis. Antimicrobial resistance is increasing, and 3rd-generation cephalosporins with macrolide or tetracycline is recommended treatment.

See also in the Micro-ID session guide

Moraxella

Small coccobacillary gram-negative rod that is transmitted from human-to-human via respiratory aerosols.

It is the cause of community infections of the upper respiratory tract (otitis media, sinusitis), especially in children. It is also a cause of “atypical” community-acquired pneumonia, especially among persons with COPD.

Gram-negative rods (GNRs)

Enterics

Rods

Aerobic

Lactose fermenters

Lactose-fermenting gram-negative rod and is abundant in the human colon and genital tract.

There are over 150 distinct serotypes that are defined by their surface antigens, O, K, and H.

-

- The O antigen is the polysaccharide unit of LPS.

- The H antigen is flagellar protein.

- The K antigen is a polysaccharide capsule present in some strains.

E. coli have pili that allow binding to a variety of epithelial cells; these in part predict where colonization and/or disease can occur. Clinical disease occurs opportunistically when organism gains access to usually sterile sites or vulnerable host (urinary tract infections, neonatal sepsis) or new virulent sub-species is acquired, as in diarrheal illnesses when fecal-oral transmission occurs.

E. coli have pili that allow binding to a variety of epithelial cells; these in part predict where colonization and/or disease can occur. Clinical disease occurs opportunistically when organism gains access to usually sterile sites or vulnerable host (urinary tract infections, neonatal sepsis) or new virulent sub-species is acquired, as in diarrheal illnesses when fecal-oral transmission occurs.

E. coli is the most common cause of urinary tract infections.

Neonatal meningitis is acquired during birth and can present with poor tone and respiratory distress. The K1 capsular polysaccharide is the main virulence factor linked with neonatal E. coli sepsis.

Sub-types that cause infectious diarrhea are:

-

- Enterotoxigenic (ETEC): Produces heat-labile toxin (LT) and stable-toxin (ST) that lead to loss of electrolytes from enterocyte; it is the most common cause of traveler’s diarrhea and is generally self-limited.

- Enteropathogenic (EPEC)

- Enteroinvasive (EIEC)

- Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC): EHEC produces Shiga-toxin and is an important cause of bloody diarrhea. It is most commonly associated with O157:H7 serotype. A low infective dose (100organisms) allows for contamination of food over wider distribution networks and larger outbreaks. Hemolytic uremic syndrome with renal failure is a dreaded complication.

- Enteroaggregative (EAEC).

Facultative gram-negative rod with a large polysaccharide capsule, which gives colonies grown on agar a mucoid appearance.

It inhabits the human upper respiratory mucosa and GI tract. It is not as ubiquitous as E.coli but can cause similar opportunistic infections (UTIs, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, and sepsis). It is notable as one of the most resistant bacteria in the Enterobacteriaceae family and is a major concern in healthcare-associated infections.

Other than opportunistic infections, distinct clinical entities due to K. pneumoniae include:

-

- Liver abscess, which frequently is associated with K1 or K2 capsular type and is more prevalent in SE Asian regions

- Aspiration pneumonia in chronic alcoholism, where necrotizing infections can be seen and sputum is described as “currant jelly,” reflecting the very mucoid nature of the pathogen

Note: K. pneumoniae pneumonia is not exclusive to alcoholism or aspiration events, but the associated tends to be a board favorite.

Enteric gram-negative rod that causes similar opportunistic infections as K. pneumoniae.

Colonies are easily spotted in the lab with their red pigment. Organisms are water loving (think about the “pink slimy stuff” that accumulates on shower curtains, water fixtures, and toilets).

Enteric gram-negative rod that causes similar opportunistic infections as K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens.

Antibiotic susceptibility is variable, and extensive drug resistance is increasing.

See also in the Micro-ID session guide

Non-lactose fermenters

Non-lactose fermenting gram-negative rods that can be easily distinguished in microbiology lab by production of H2S.

Gallbladder colonization with chronic carrier state (and source of on-going infection in others) is possible. Two species are most relevant to human disease and cause very different disease:

-

- Typhoid fever: Salmonella typhi is the cause of typhoid fever and is found in humans only. Transmission is fecal-oral. Bacteremia leads to infection of the reticuloendothelial system, especially the liver and spleen. Fever is due to the activity of endotoxin. S. typhi capsule, Vi antigen, is major virulence factor. Vaccines (live and capsular) are available with modest efficacy at disease prevention.

- Gastroenteritis: Salmonella enterica is found in the enteric tract of humans and animals. Transmission is through fecal-oral route/contaminated foods. S. entericais causes an invasive diarrhea with potential for bacteremia and sepsis. Patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathy are at particularly increased risk for invasive disease and osteomyelitis due to Salmonella.

Non-lactose-fermenting, non-motile gram-negative rod.

It is transmitted by fecal-oral route and has an incredibly low infective dose (1–10 organisms), allowing it to cause disease outbreaks, often in environments of care such as daycare or nursing homes. Shigella produces Shiga-toxin and is the cause of classic “dysentery,” a severe watery diarrhea that results from organism invasion of the enterocyte. Systemic infection generally does not occur.

Comma-shaped microaerophilic gram-negative rod.

It is found in human and mammalian colon and transmitted via fecal-oral route. It causes watery diarrhea and cramping. It invades the mucosal epithelium but does not penetrate further. Bloody diarrhea is uncommon but may be seen in children. Post-infectious immunologic phenomena have been more closely linked with Campylobacter infections than other enteric infections. Reactive arthritis and Guillain-Barre are late onset immune-mediated complications.

Non-lactose fermenting gram-negative rods that produce urease.

They are highly motile and characteristically demonstrate “swarming motility” on blood agar plates. They are found in soil and water in the environment and can inhabit the human colon. Clinical disease is most commonly in the urinary tract, where urease acts as a virulence factor, forming ammonia, which leads to struvite stone formation and can cause urinary obstruction.

See also in the Micro-ID session guide

Anaerobic

Most abundant anaerobe in the human colon.

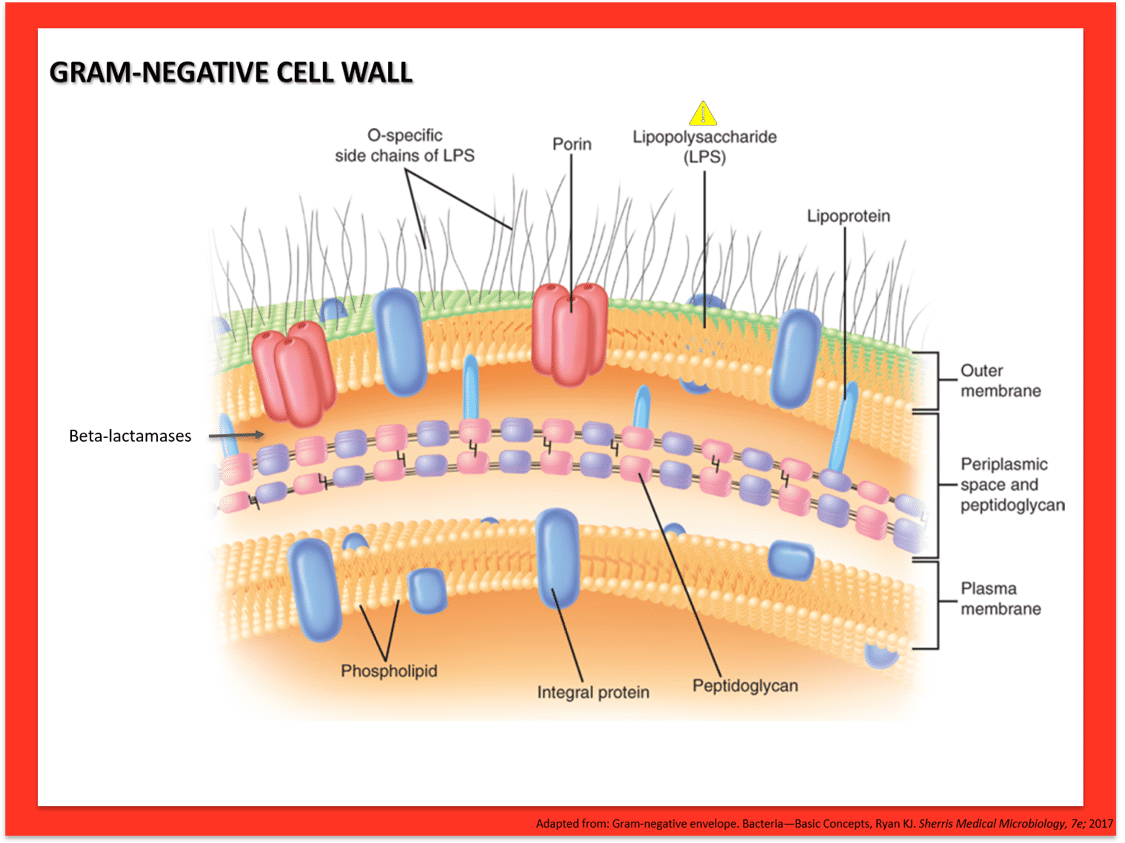

Clinical infection can occur when breakdown in the usual anatomic barrier occurs, allowing spread of the bacteria to the blood or peritoneum (e.g., penetrating abdominal trauma, bowel surgery). It is the anaerobe to be concerned about “below the diaphragm.” Plasmid-encoded beta-lactamases are common; metronidazole is preferred treatment.

Anerobic gram-negative rod that is member of the normal flora in the oral cavity and throat, and is the anaerobe to be concerned about in infections “above the diaphragm” (e.g., polymicrobial abscesses in the lung or brain).

Anaerobic gram-negative rod that is member of normal human flora throughout the body: mouth, gingivae, GI tract, and female genital tract.

As with other infections due to normal human flora, disease can occur when there is breakdown of normal mucosal barriers. The major clinical infectious disease associated with Fusobacterium is “Lemierre’s syndrome,” which refers to infectious thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein as a complication of acute pharyngitis and peri-tonsillar abscess. Septic pulmonary nodules may also be seen.

Cocco-bacilli

Gram-negative coccobacilli that tend to have bipolar staining, giving them the appearance of a safety pin on gram stain.

They are primarily animal pathogens.

There are three species of note in human disease:

-

- Y. pestis

- Y. pseudotuberculosis

- Y. enterocolitica

In humans, Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica cause disease in the GI tract after ingestion of contaminated food or water. Disease is characterized by dysentery syndrome with watery diarrhea. Mesenteric lympadenitis is a distinguishing feature. There is predilection for the terminal ileum and presentations can be mistaken for acute appendicitis.

Y. pestis is a specialized variant related to pseudotuberculosis. Instead of entering through GI tract, it is transmitted by the bite of an infected flea and transmitted via dermal lymphatics to cause “Bubonic Plague,” the most common presentation, with regional painful lymph node swelling (bubo); the site of the bite may be inapparent. There are several clinical variants of plague depending on the site of inoculation:

-

- Bubonic plague

- Septicemic plague

- Pneumonic plague

Its capacity to cause disease with inhalation classifies Y. pestis as Category A bioterrorism agent/disease. Complications of infection include sepsis, DIC, and terminal digital necrosis—lending it the name “black death.”

Curved rods

Comma-shaped gram-negative rods that are oxidase positive, which distinguish them from the Enterobacteraciae.

Saltwater environments are the preferred habitat for Vibrio spp. Major human pathogens include Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus

Vibrio cholerae inhabits the human colon and can be found in shellfish. Transmission is fecal-oral and usually in relation to contaminated water sources (as opposed to food-borne). Disease is characterized by massive watery diarrhea (“rice-water” diarrhea) that is due to Cholera toxin, which is an AB toxin that results in accumulation of cAMP and outflow of Cl and H20. Morbidity and mortality from cholera is related to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Therapy is mostly supportive with oral rehydration, fluid, and electrolyte depletion.

-

- Vibrio parahaemolyticus causes watery diarrhea after consumption of contaminated raw seafood. The diarrhea is mediated to enterotoxin that is similar to cholera.

- Vibrio vulnificus is found in warm seawater or brackish water. It can cause a severe cellulitis with hemorrhagic bullae when inoculated into skin by trauma or other breaks in skin (e.g. shellfish handlers). Ingestion of contaminated raw shellfish can cause diarrheal illness or invasive disease with sepsis. Immunocompromised persons and those with advanced liver disease are at greatest risk for severe complications.

Comma-shaped microaerophilc gram-negative rod with polar flagella.

It is distinctive for the production of urease that allows the organism a niche ability to inhabit the low pH environment of the human stomach, where it was thought to be merely a commensal organism until the early 1980s. It is now recognized as a cause of human disease that affects the gastric mucosa (does not invade). Specific factors VacA (induces apoptosis) and CagA (induces inflammatory state in epithelial cells) are linked to virulence. Associated diseases with H. pylori infection are:

-

- Gastritis

- Peptic ulcers

- Gastric adenocarcinoma

- Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma

It is one of very few bacteria recognized to have oncogenic potential.

Respiratory

Sometimes referred to as “H. flu,” are a small gram-negative coccobacilli.

The species are divided into typeable and non-typeable strains based on the presence or absence of polysaccharide capsule, respectively. H. influenzae is fastidious and requires enriched media for growth. Specifically, factors X (hemin) and V (NAD) are required; chocolate agar provides both. The habitat is the upper respiratory tract and transmission is via respiratory droplets.

The polysaccharide capsule is the major virulence factor for causing invasive infections. There are six typeable/encapsulated strains (a-f); type b (Hib) is the most virulent, causing 85% of all invasive syndromes. Though vaccination has reduced rates of infections, H. influenzae is an important cause of bacterial meningitis, especially in infants with immature immunity. Hib is the most important cause of epiglottitis, which is an airway emergency, and is now relatively uncommon.

Non-typeable strains of H. influenzae are among the most common bacterial causes of respiratory tract infections:

-

- Otitis media

- Sinusitis

- Community-acquired pneumonia

Beta-lactamases are relatively common. Third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone) is the treatment of choice for invasive infections.

Small gram-negative rod that can inhabit the respiratory tract and is spread via respiratory droplets.

Laboratory identification requires specialized media: Bordet-Gengou agar or PCR testing. Main virulence factors are the Pertussis toxin, an AB toxin that results in peripheral lymphocytosis, and tracheal toxin, which causes damage to the ciliated epithelium of the trachea.

Clinical disease is Pertussis, also called “whooping cough.” Infants and young children are at greatest risk for severe disease. Whooping cough is characterized by three clinical phases:

-

- The catarrhal stage

- The paroxysmal phase, where the inspiratory ‘whoop’ is heard at the end of prolonged coughing spell and post-tussive emesis is frequently described

- The convalescent phase

Vaccination with acellular purified protein is recommended for all children.

Treatment of disease is with tetracycline or macrolide.

Gram-negative rod that replicates intracellularly and stains poorly, so is not commonly seen on gram-stain.

Silver-impregnated stain or fluorescent antibody staining is used to identify organism in clinical specimens. The natural habitat is environmental water sources, and transmission to humans occurs via aerosolized water. Human-to-human transmission does not occur. Specialized media that contains cysteine and iron is required for growth; buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar is most common.

Legionella is a cause of atypical pneumonia that can be community acquired or nosocomial. Infections are almost always due to serotype 1. A water source (e.g., air conditioners, hot tubs, humidifiers, ventilatory devices) is almost always implicated but may not always be found. Clinical disease can range from nonspecific febrile syndrome, Pontiac fever, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure. Cell-mediated immunity is important host-defense against this intracellular pathogen, so patients at risk of severe disease include older age, excess alcohol use, HIV/AIDS and other immunosuppressed patients, and tobacco use.

Urinary antigen is an effective and rapid diagnostic tool.

Macrolides or respiratory fluoroquinolones are used for treatment.

Opportunistic

Pseudomonad of most concern in human infections.

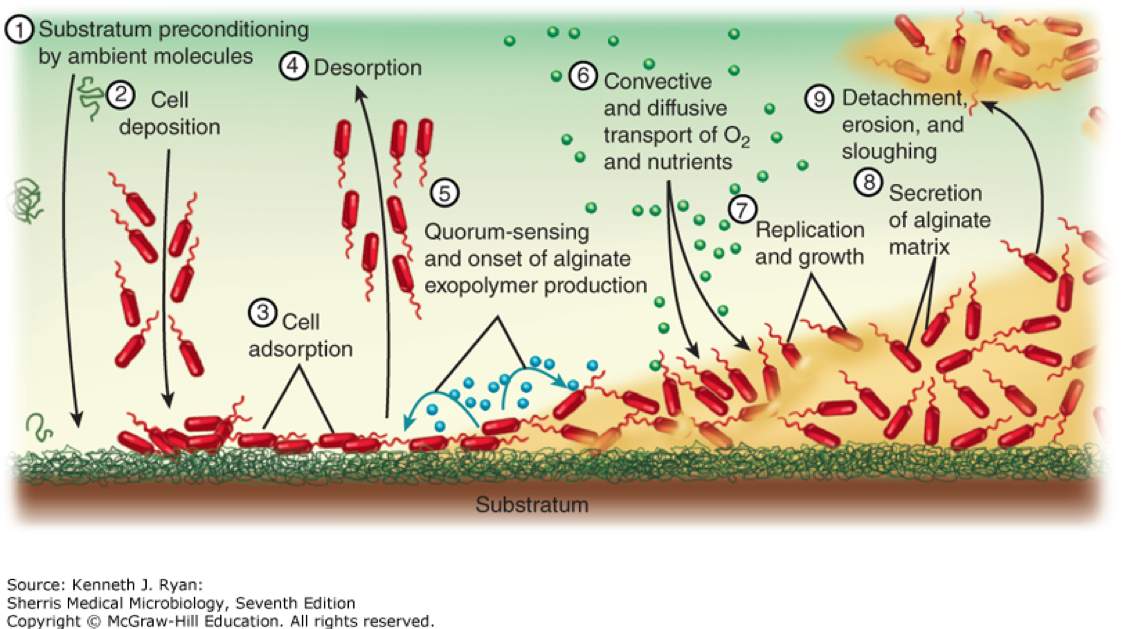

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an aerobic gram-negative rod that is abundant in environmental water sources. More rarely, it can also inhabit the skin, upper respiratory tract, and GI tract. It is non-lactose-fermenting and oxidase positive, which is typically used to quickly differentiate from other gram-negative infections caused by the Enterobacteraciae. It produces pyocyanin, which gives a blue-green pigment to colonies in the lab, and can be seen clinically on wound infections due to Pseudomonas. Virulence factors include pili and a capsule that facilitate attachment and inhibit phagocytosis. Certain strains are notable for production of thick glycocalyx that produces a biofilm that is particularly difficult to eradicate (see image below).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an aerobic gram-negative rod that is abundant in environmental water sources. More rarely, it can also inhabit the skin, upper respiratory tract, and GI tract. It is non-lactose-fermenting and oxidase positive, which is typically used to quickly differentiate from other gram-negative infections caused by the Enterobacteraciae. It produces pyocyanin, which gives a blue-green pigment to colonies in the lab, and can be seen clinically on wound infections due to Pseudomonas. Virulence factors include pili and a capsule that facilitate attachment and inhibit phagocytosis. Certain strains are notable for production of thick glycocalyx that produces a biofilm that is particularly difficult to eradicate (see image below).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most important causes of nosocomial infections. It can be difficult to treat and is associated with poorer outcomes overall. As an opportunist, it can cause infections in virtually all systems:

-

- Bloodstream infections/sepsis

- Pneumonia

- UTI

- Wounds

- Devices infections

- Neurosurgical/CNS

These infections are more common in patients with exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics and those patients with significant immunosuppression and multiple medical co-morbidities.

Specific clinical syndromes of note include:

-

- Pneumonia in cystic fibrosis or other forms of bronchiectasis or severely altered respiratory anatomy

- Burn infections

- Ecthyma gangrenosum: Cutaneous necrotic popular eruption as a result of P. aeruginosa bacteremia in patients with severe immunosuppression, most often related to myeloablative chemotherapy

- Otitis externa due to P. aeruginosa can occur in immunocompetent persons where it is simply known as “Swimmer’s ear.” A more serious and potentially life-threatening version occurs in uncontrolled diabetes where it is termed “malignant otitis externa.”

- Infectious keratitis or conjunctivitis is frequently associated with contact lenses and contaminated cleaning solution or ophthalmic medications.

- “Hot-tub folliculitis” is a follicular eruption as a result of soaking in hot tubs heavily colonized with the organism. Eruption is most often limited

Treatment of Pseudomonas is difficult to naturally occurring resistant porins that restrict entry to many antibiotics, and variable plasmid mediated resistance mechanisms. They are uniformly resistant to penicillin, ampicillin, 1st- and 2nd-gen cephalosporins, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, ertapenem, and some fluroquinolones. There are few oral agents for use in treating pseudomonal infections.

Current anti-pseudomonal agents are:

-

- Piperacillin-tazobactam

- Cefepime

- Ceftazidime

- Cefoperazone

- Ceftolozane-tazobactam

- Aztreonam

- Ciprofloxacin

- Levofloxacin

- Carbapenems (except ertapenem)

- Aminoglycosides (except streptomycin and kanamycin)

- Polymixins

See also in the Micro-ID session guide

Zoonotic

Small gram-negative coccobacillus. It is not routinely grown in the laboratory due to risk to lab personnel; it grows slowly and best on cysteine-glucose blood agar, but it can grow on chocolate agar.

F. tularensis can be found in many wild mammals of the northern hemisphere, especially rabbits, deer, and rodents. They acquire the bacteria via Dermacentor tick-bite. Infected mammals may not always show signs of disease. Humans are incidental hosts and can be infected by tick-bite, contact, ingestion, and aerosol. The latter route of transmission assigns F. tularensis to Category A Bioterrorism agent/disease.

Clinical syndromes depend on the site of inoculation and include:

-

- Ulceroglandular (most common)

- Oculoglandular

- Typhoidal tularemia (ingestion)

- Pneumonic tularemia

Treatment is Streptomycin or gentamicin in combination with doxycycline.

Small facultative intracellular gram-negative rods that slow growing and microscopically resemble Haemophilus, but are rarely seen on gram stain of clinical specimens.

Brucella is found in domestic livestock, where it causes a chronic infection of mammary tissue, placenta, and reproductive organs. It is a cause of abortions in cattle, goats, and pigs.

Clinical infection in humans occurs usually by consumption of unpasteurized dairy products or through occupational exposure with infected animals. Brucellosis causes a systemic disease that can mimic tuberculosis with fever, chills, and night sweats; the fever is periodic and nocturnal and referred to as “undulant fever.” Chronic infection of the reticuloendothelial system ensues, with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly, and serves as reservoir for episodic bacteremia. Focal infection of the bones, joints, GU system, and heart are occasionally seen.

Small gram-negative coccobacilli that employ unique strategy of an intraerythrocyte niche, which facilitates its transmission cycle between tick and mammal.

Pathogenically, the niche in RBC results in tumor-like angiogenic lesions that accumulate in capillaries

-

- B. quintana is known as “trench fever” due to its prevalence in World Ware I. Humans are the mammalian reservoir, and human body louse is vector. In modern times, it is associated with rare cases of endocarditis.

- B. henselae is found in cats where little disease is caused. Humans are incidental hosts. There are two main clinical syndromes:

- Cat-scratch fever is febrile lymphadenitis with systemic symptoms that can be mistaken for lymphoma; it tends to occur more common in children and young adults.

- Bacillary angiomatosis is almost exclusively seen in patients with AIDS and other forms of advanced cell-mediated immunodeficiency; it consists of proliferative disease in small vessels of skin and visceral organs and can be mistaken for Kaposi Sarcoma.

Obligate intracellular parasites and not well-visualized on gram-stain.

It can survive and multiply within alveolar macrophages due to resistance to lysosomal enzymes. Its growth cycle is unique in that it includes a form that is spore-like, allowing it to persist for prolonged periods in the environment. C. brunetti infects a wide variety of mammals and has dramatic tropism for placental tissue. Clinical infectious disease, or Q fever, is often encountered in humans with some exposure to parturient livestock. Notably though, C. burnetii is highly infectious, and the environmental persistence allows for disease via inhalational route; it is designated Category B bioterrorism agent/disease. Clinical disease is variable and can present with interstitial pneumonia, granulomatous hepatitis, and rarely endocarditis. Life-threatening infection is not common.

Small gram-negative rod that is found as normal flora of the feline mouth.

It is frequently encountered in infected wounds of cat bites. Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk of systemic infection.

Small gram-negative rod that is found as normal flora of the canine mouth.

It is frequently encountered in infected wounds of dog bites. Immunosuppressed patients and patients with advanced liver disease are at particular risk of systemic infection.