1Identify the temporal fossa and temporalis muscle.

2On a skull, identify the borders of the infratemporal fossa (ITF) and the foramina that connect it other regions in the head.

3Clean the masseter muscle on one side of the face and remove it from the mandible.

4Use an autopsy saw to cut the mandible and zygomatic arch on one side. Remove the bones to access the infratemporal fossa.

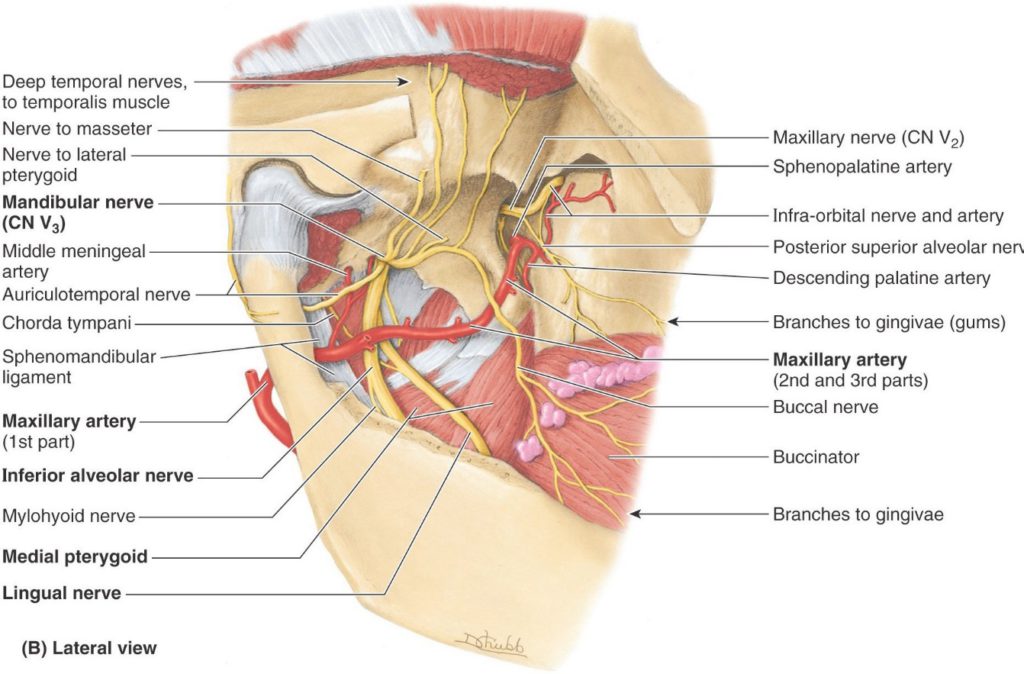

5Clean and identify the pterygoid muscles and major branches of the mandibular nerve (V3) and maxillary artery in the ITF.

6Disarticulate the temporomandibular joint on one side and study its anatomy.

7Remove the body of the mandible to provide a lateral view of the floor of the mouth. Clean and identify muscles, nerves, vessels, and salivary glands.

8With the mandible removed, identify structures in the submandibular triangle of the neck.

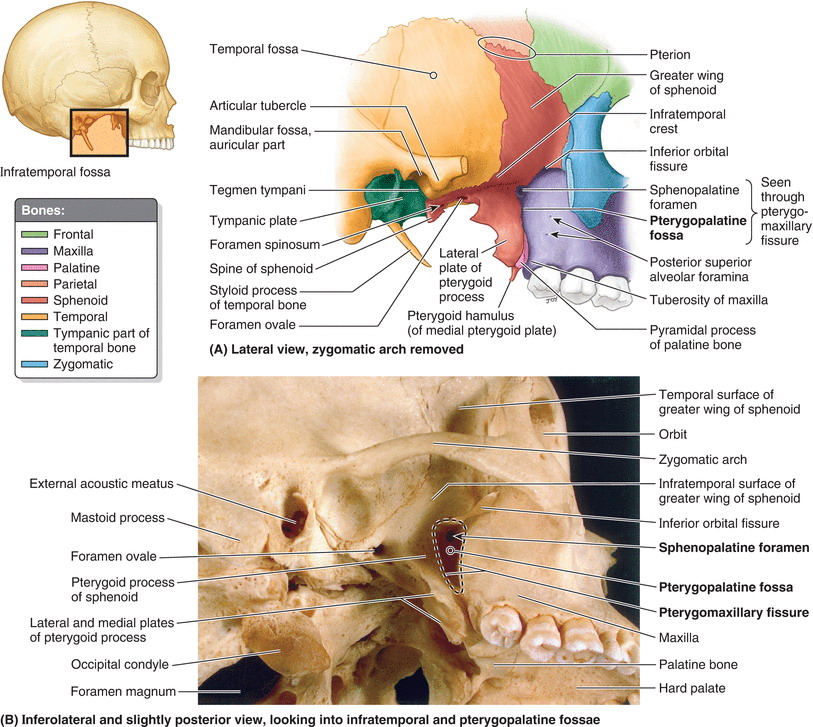

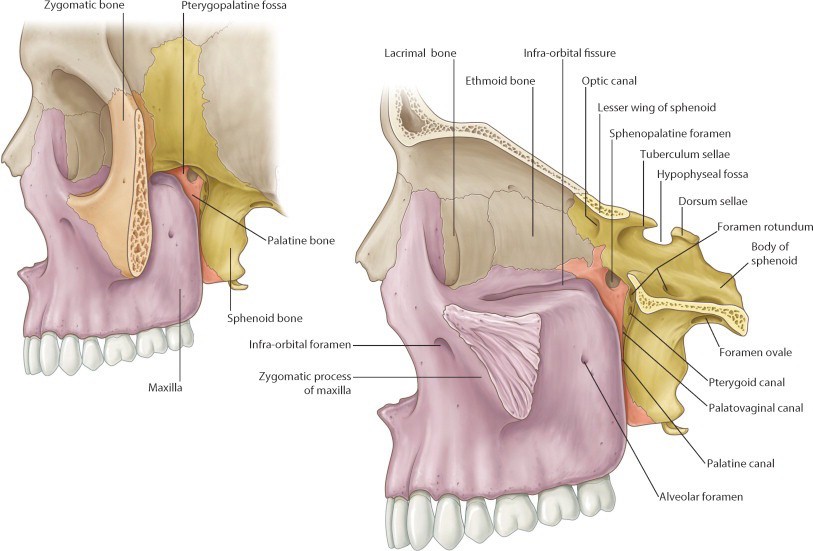

9On a skull, identify the pterygopalatine fossa and its associated foramina.

Bony Anatomy: Temporal and Infratemporal Fossae

On a skull, identify the temporal fossa, infratemporal fossa (ITF), and temporomandibular joint(TMJ).

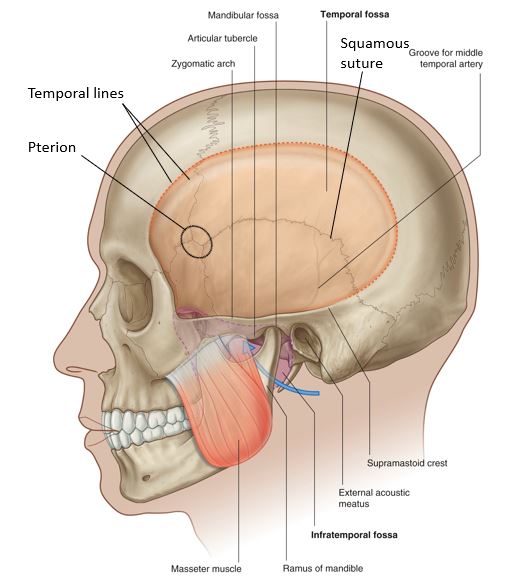

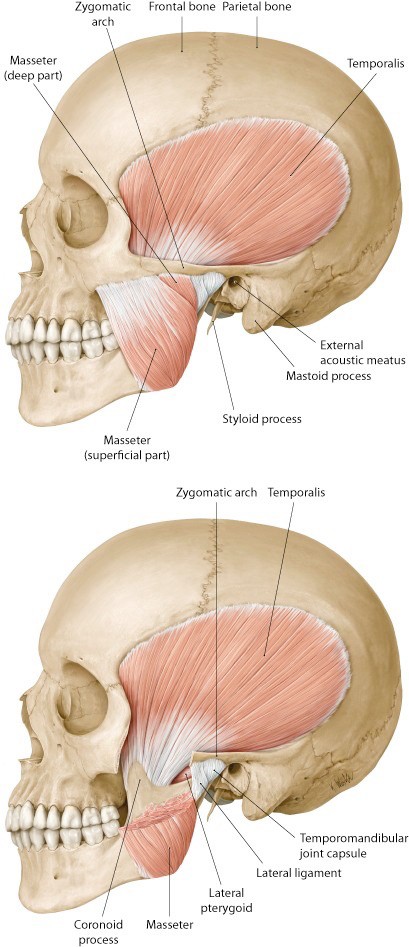

The following bony parts relate to the temporal fossa (Figure 30.1):

What is the clinical significance of the pterion?

Go to the cadaver and answer this: Which structure fills the temporal fossa?

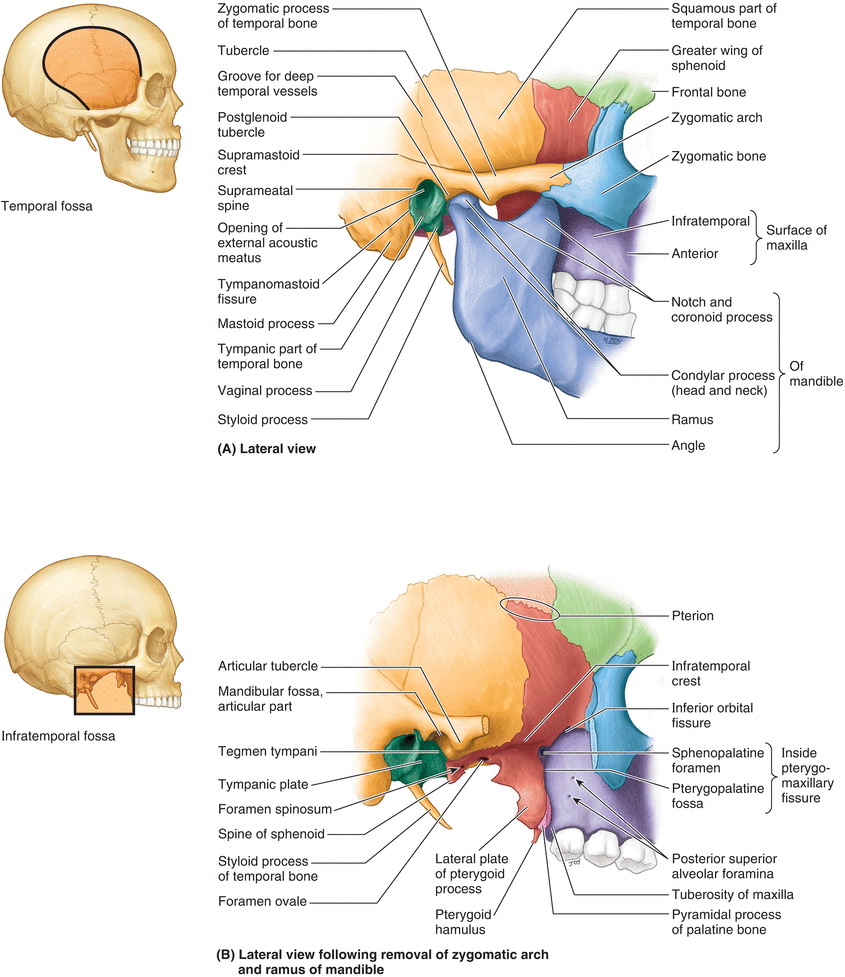

Now locate the infratemporal fossa (ITF), deep to the ramus of the mandible (removing the mandible will help). The bony borders of the ITF are (Figure 30.2):

■Lateral wall: Ramus of mandible

■Medial wall: Lateral pterygoid plate of sphenoid bone

■Anterior wall: Body of maxilla (contains the maxillary sinus)

■Posterior: Tympanic part of temporal bone and styloid process

■Roof: Greater wing of sphenoid bone

Using a pipe cleaner, probe these bony openings related to the ITF:

■Foramen ovale (in the roof)

■Foramen spinosum (in the roof)

■Pterygomaxillary fissure (in the medial wall)

■Inferior orbital fissure (in the anterior wall)

Identify these features of the temporal bone (see Figure 30.2):

■Mandibular fossa (part of the TMJ)

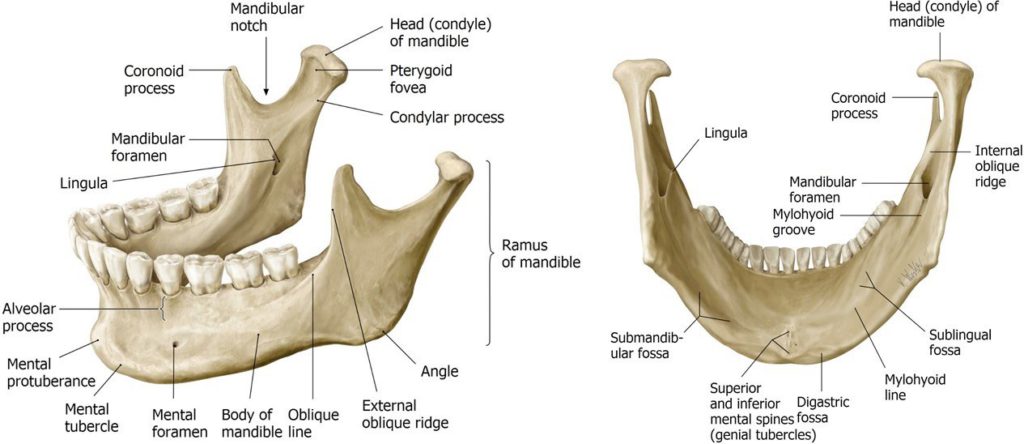

On an isolated mandible, identify the following (Figure 30.3):

■Ramus, body, and angle

■Coronoid process (temporalis muscle inserts here)

■Condylar process and condyle (head)—the condyle is part of the TMJ

■Mandibular notch

■Mandibular foramen (for the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels)

■Mylohyoid groove (for the mylohyoid nerve)

Dissection of infratemporal fossa

We will dissect the infratemporal fossa on one side of the head only. Do this on the “deep” side of the face dissection that you completed earlier (the side where the parotid gland was removed).

■Clean the surface of the masseter muscle.

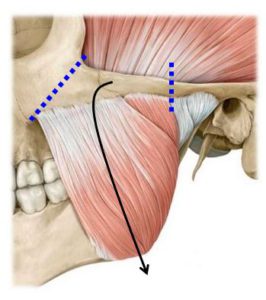

■The masseter is a muscle of mastication. It arises above from the zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch. It inserts below into the external surface of the mandibular ramus and angle of the mandible. What is the function of the masseter?

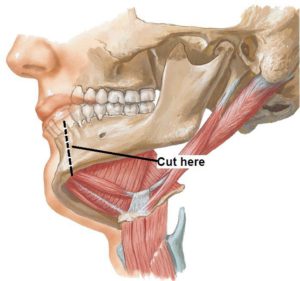

■Use an autopsy saw to make cuts through the zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch, as shown in Figure 30.4. Loosen up the detached segment of zygomatic bone and reflect it downward, along with the attached masseter muscle (Figure 30.4). As you pull down, use a chisel or scissors to scrape/cut away the masseter from its attachment to the external surface of the mandibular ramus. Leave the reflected masseter muscle and zygomatic bone fragment hanging from the mandible or remove it entirely by cutting it at its distal attachment to the angle of the mandible. The external surface of the mandible is now visible.

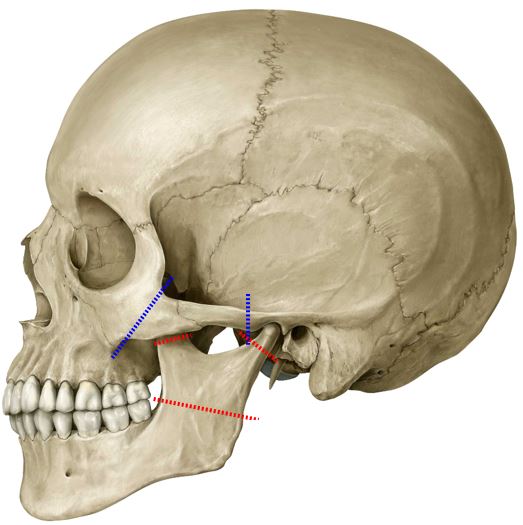

■Use the autopsy saw to make three cuts in the mandible (RED lines shown in Figure 30.5).

■Cut through the coronoid process and through the neck of the condylar process.

■Deeply score the bone of the mandibular ramus horizontally as shown—but don’t saw all the way through the bone. Use a chisel and hammer to break the ramus into bone fragments. Wear eye protection!! Be careful because this may sever underlying nerves. Use bone Rongeurs to pull away the bone fragments.

■The temporalis muscle arises from the floor of the temporal fossa. It inserts on the coronoid process of the mandible and inner surface of the ramus. See Figure 30.6. What are the actions of the temporalis muscle?

■Grasp the detached upper portion of the cut coronoid process with forceps and reflect it superiorly with the temporalis. You will notice that the temporalis inserts quite far inferiorly on the inside of the mandibular ramus. The muscle is very thick behind the zygomatic bone. You will need to remove the distal part of the temporalis with scissors to get a clear view of the ITF. Take care to probe through the distal part of the temporalis before cutting, as the buccal nerve often passes through it.

■Keep reflecting the temporalis upward until you can see the bony floor of the temporal fossa. Retain the deep temporal arteries and nerves if you can. They enter the deep surface of the temporalis, right against the bone.

After the temporalis muscle has been reflected, its inferior muscle fibers cleared, and the fragments of mandibular ramus removed, the ITF will be visible.

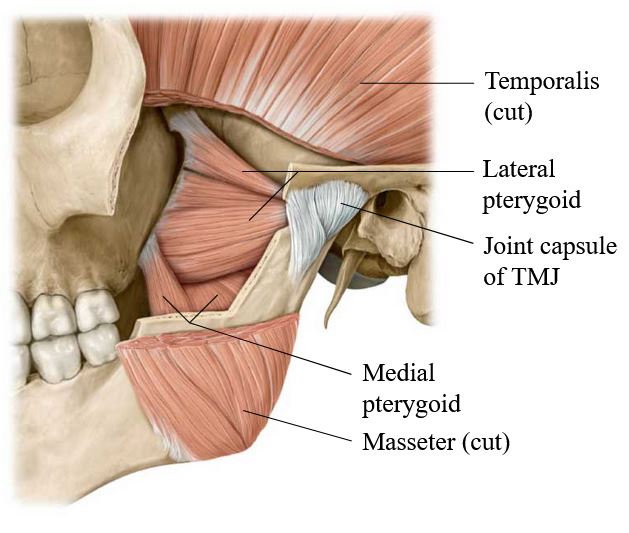

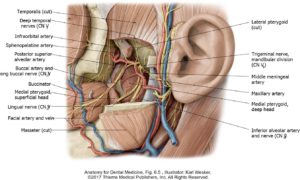

Identify and clean the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles (Figure 30.7).

The ptergygoid venous plexus will appear as a network of dark veins in the connective tissue surrounding the pterygoid muscles.

■The lateral pterygoid muscle arises from the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate (sphenoid bone). It has upper and lower heads. Where does the lateral pterygoid insert? What are its actions?

■The medial pterygoid muscle arises from the medial surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. Where does it insert? What are its actions?

Fun Fact

The medial pterygoid is essentially the mirror image of the masseter, only it attaches to the internal surface of the mandibular ramus, not the external, as the masseter does.

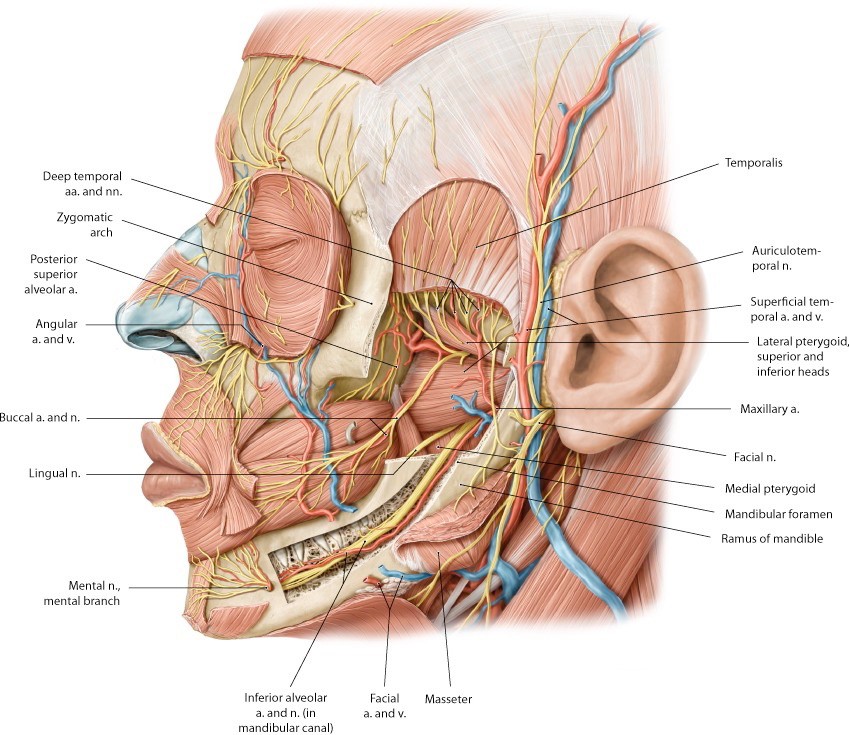

Lingual and Inferior Alveolar Nerves

■Identify the lingual nerve and the inferior alveolar nerve on the external surface of the medial pterygoid muscle (Figure 30.8). They are sandwiched between the muscle and the internal surface of the mandible. The inferior alveolar nerve may have been transected when the mandible was cut.

■Separate the inferior alveolar artery from the nerve. It is a branch of the maxillary artery.

■The inferior alveolar nerve and vessels pass into the mandible via the mandibular foramen. They course through the mandible within the mandibular canal. See Figure 30.8. What is the function of the inferior alveolar nerve?

Buccal Nerve (V3)

Identify the buccal nerve (of V3) passing between the two heads of the lateral pterygoid on its way to the cheek. See Figure 30.8. It might be hidden by the inferior fibers of the temporalis and sometimes passes through the muscle. It is a sensory nerve supplying the skin on the external cheek and the mucous membranes inside the cheeks in the oral cavity.

Note

Note that the buccal branch of VII is motor; the buccal nerve of V3 is sensory.

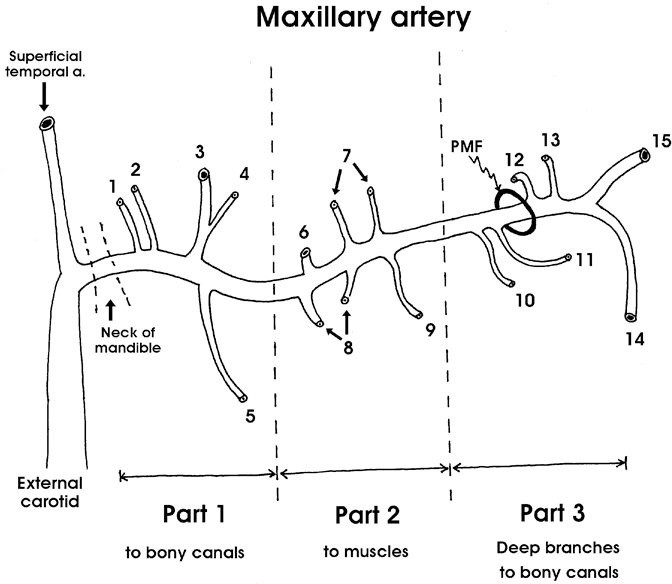

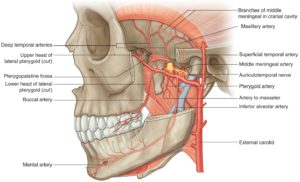

Maxillary Artery

The maxillary artery is one of the two terminal branches of the external carotid. What is the other one?

The maxillary artery (Figure 30.9) enters the ITF deep to the condylar process of the mandible. Once in the ITF, it passes either superficial or deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle. You will need to do some cleaning to determine which is the case in your donor. If it passes deep, you won’t see much of the artery until you remove the lateral pterygoid (instructions on this are given later).

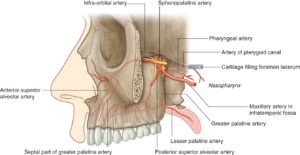

The distal part of the maxillary artery leaves the infratemporal fossa via the pterygomaxillary fissure and enters the pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 30.9).

Dissection of the branches of the maxillary artery is difficult! Our goal is to trace it through the ITF to the pterygomaxillary fissure and try to identify several of its major branches. Figure 30.10 is a sketch that lists ALL the branches of the maxillary artery. We will seek out only a few of these today. Don’t sweat the small branches.

Key to Maxillary Artery “Wonder” Drawing

Part 1 = Branches enter bony canals/foramina

-

- Deep auricular artery

- Anterior tympanic artery

- Middle meningeal artery

- Accessory branch of meningeal artery (when present)

- Inferior alveolar artery

Part 2 = Muscular branches

Part 2 passes superficial or deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle (~ 50/50)

-

- Masseteric artery

- Anterior and posterior deep temporal arteries

- Pterygoid branches

- Buccal artery

Part 3 = Deep branches are given off near the pterygomaxillary fissure or within the pterygopalatine fossa.

-

- Posterior superior alveolar artery

- Infra-orbital artery

- Pharyngeal branch (to nasopharynx)

- Artery of pterygoid canal

- Descending palatine artery

- Sphenopalatine artery

Removal of lateral pterygoid muscle

To better see the nerves and vessels in the infratemporal fossa, the lateral pterygoid muscle will be removed. Carefully remove the lateral pterygoid muscle in pieces with scissors and forceps.

■Identify the buccal nerve passing between the two heads of the lateral pterygoid. Preserve this nerve as the muscle is removed.

■Locate and clean the maxillary artery as you remove the lateral pterygoid. Look for these branches of the artery as you dissect (Figures 30.9 and 30.11):

■Middle meningeal artery. It exits through the roof of the ITF through which foramen? What is the function of the middle meningeal artery? What is its clinical importance in the case of skull fracture?

■Inferior alveolar artery: Accompanies the nerve of the same name.

■Deep temporal arteries: Ascend to the deep surface of the temporalis

Use the middle meningeal artery as a guide to find the auriculotemporal nerve. Oddly enough, the nerve splits around the middle meningeal, then courses laterally, deep to the parotid gland. After leaving the ITF, the auriculotemporal nerve ascends to the scalp with the superficial temporal vessels. This is a toughie to find!

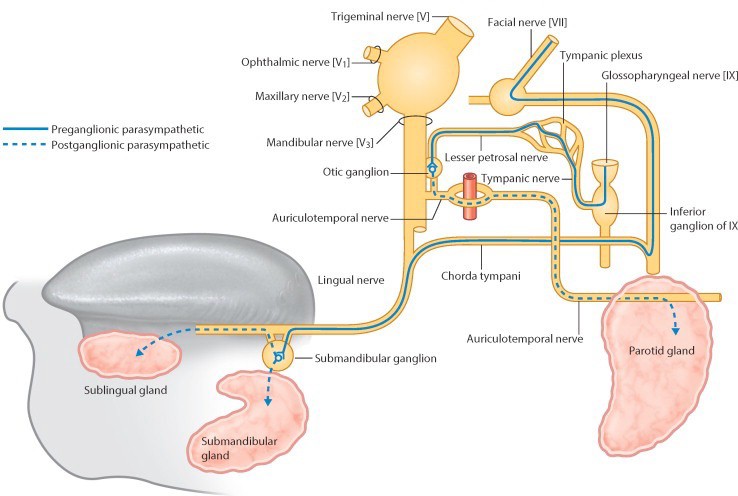

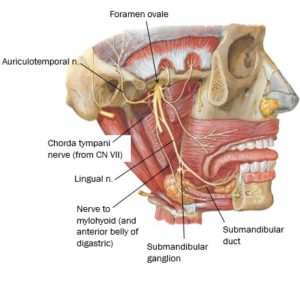

Chorda Tympani Nerve (From CN VII)

■Trace the lingual nerve superiorly as high as you can.

■The chorda tympani nerve (from CN VII) leaves the tympanic cavity and enters the ITF through a small crack = the petrotympanic fissure. Once in the ITF, the tiny chorda tympani nerve joins the lingual nerve from behind. Chorda tympani carries two functional types of nerve fibers. What are they?

■The nerve fibers in the chorda tympani travel to and from their targets (salivary glands & tongue) by “hitching-a-ride” on the lingual nerve.

Finding the chorda tympani joining the lingual nerve makes you a rockstar!

Chalk Talk

The pathway of parasympathetic innervation of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands goes through the ITF. Sketch it if you can. Also sketch how taste fibers from the anterior 2/3 of the tongue are transmitted to the CNS. [Consult the Conley-gram on cranial nerve VII after lab]. See Figure 30.13.

Chalk Talk

Discuss the pathway of parasympathetic innervation of the parotid gland. It also goes through the ITF. See Figure 30.13.

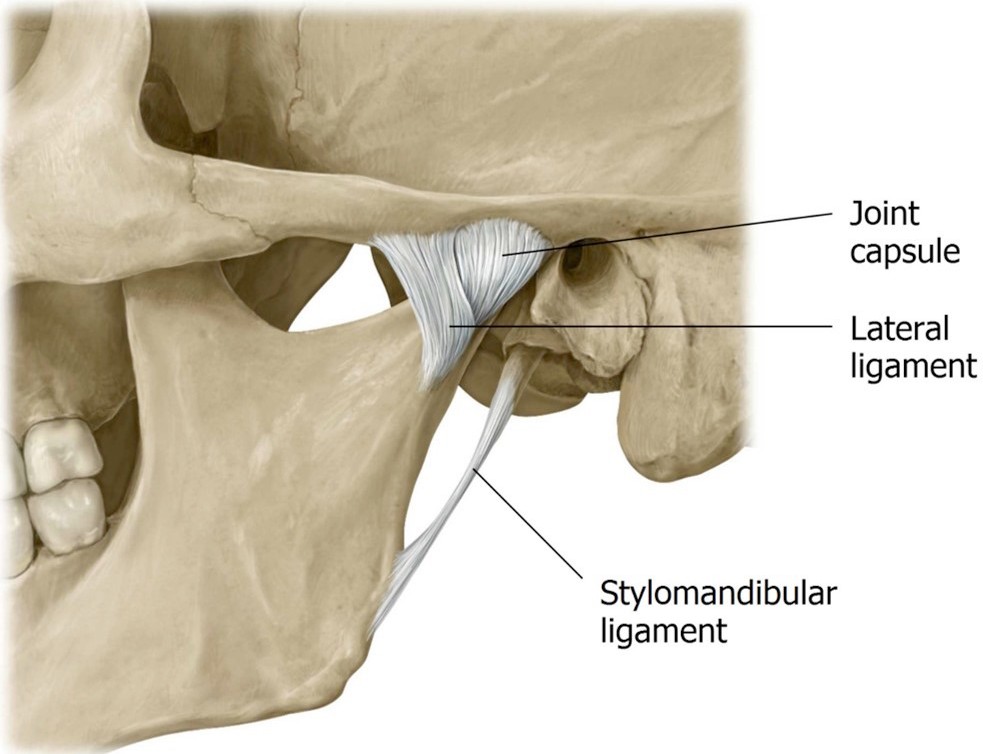

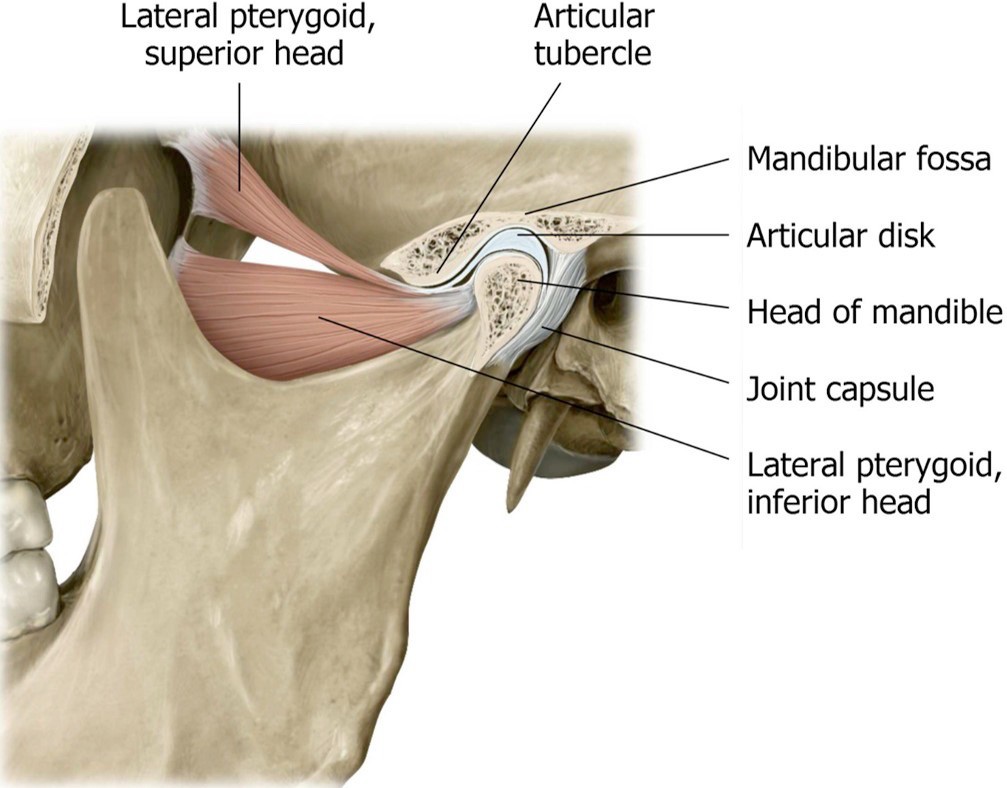

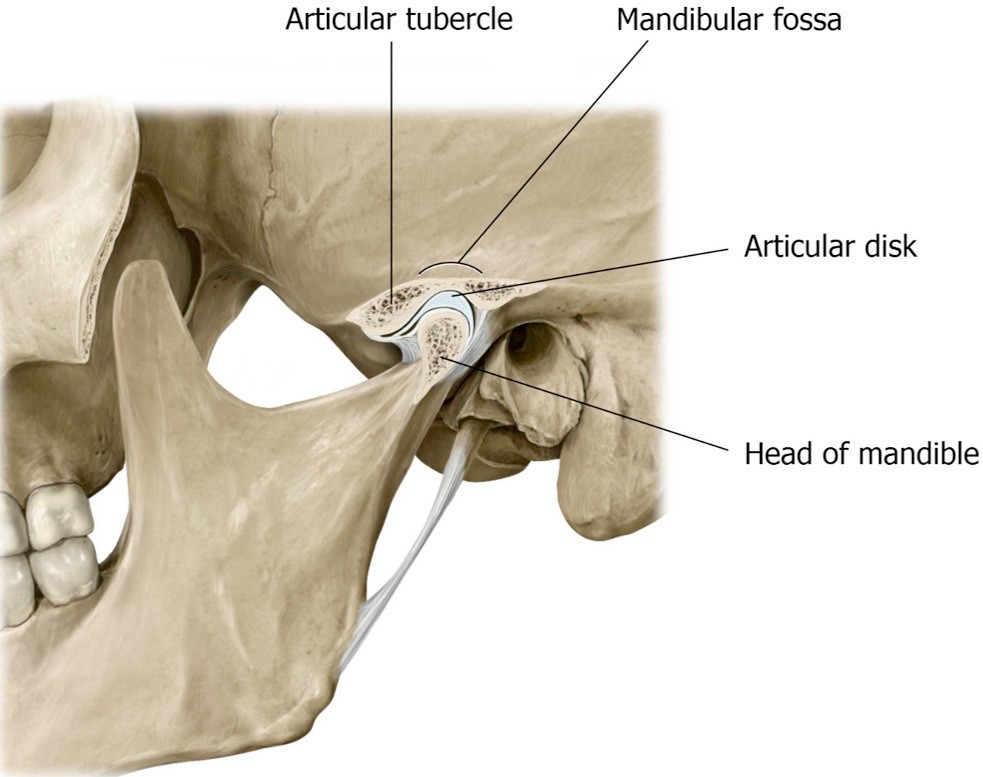

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

Review the anatomy of the TMJ. See Figure 30.14. Its bony parts are the condyle of the mandible + the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. It’s a modified hinge joint that also has translational movements (forward and backward).

■Wiggle the stump of the condylar process of the mandible that is left in your donor, so you have an idea of the location of the TMJ.

■The TMJ is a synovial joint. It is surrounded and reinforced by an articular capsule and ligaments. Remove any remaining parts of the lateral pterygoid muscle and cut the capsule with a scalpel to open the TMJ.

■Identify the articular disc (meniscus) made of fibrocartilage. The articular disc divides the internal TMJ cavity into upper and lower joint compartments.

■The lateral pterygoid muscle inserts into the mandible, articular capsule, and articular disc. Thus, when the mandible is protruded, the articular disc moves forward with the condylar head.

■With forceps or rongeurs, grasp and tug hard to remove the condylar process of the mandible, thus disarticulating the TMJ. Note the articular cartilage (different from the articular disc) on the head of the condylar process. It may be eroded due to lifetime wear on the TMJ.

Where is the articular disc? It may be attached to the bone fragment, or it may remain attached to the TMJ capsule in your donor. Ask your instructor for help.

Lateral Approach to the Floor of the Mouth

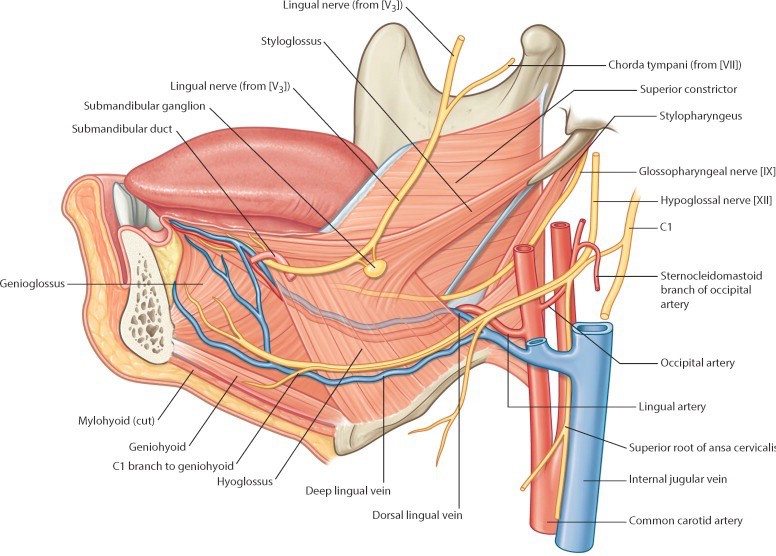

Now let’s trace the nerves forward from the ITF to the floor of the mouth. We will do this work on the same side as the ITF dissection.

Remove the lower lip.

■Make a vertical midline incision in the lip from the oral fissure to the tip of the chin. Cut away the lower lip from the mandible externally. Clean tissue from the body of the mandible.

■Transect the mandible with an autopsy saw or hacksaw, off the midline a bit (Figure 30.15). Cut downward vertically between the incisor teeth. This will keep the geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles intact.

■With scissors detach the anterior belly of the digastric and mylohyoid muscles from the inferior surface of the mandible and reflect them down.

■Pull the mandible away from the head to apply traction, then reach into the oral cavity and use a scalpel or scissors to cut away the oral mucosa where it is attached to the lingual aspect of the lower gums.

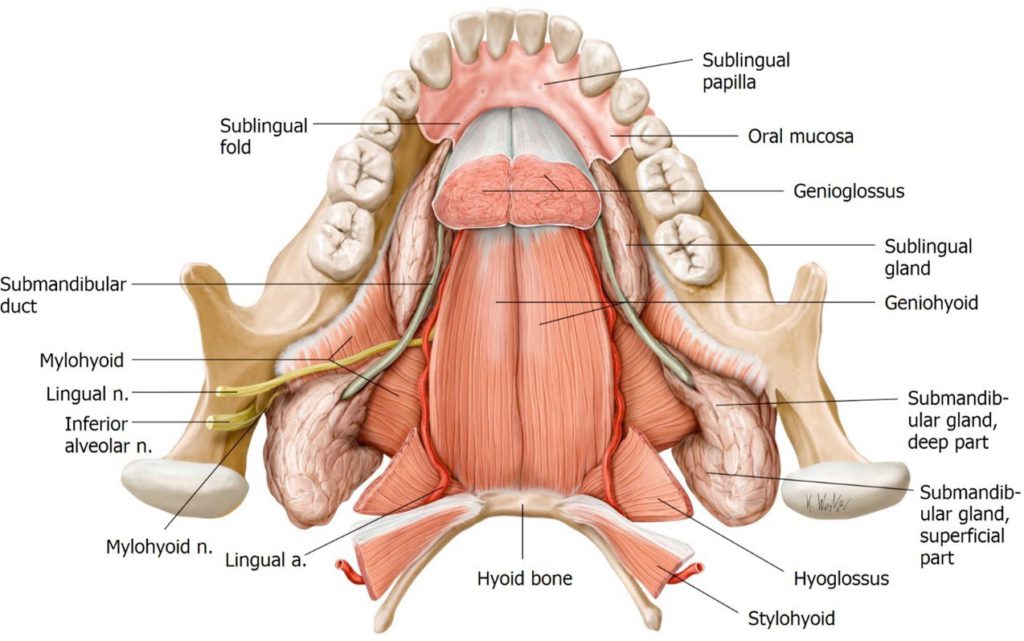

With the mandible now removed, we need some landmarks:

■Trace the lingual nerve forward from the ITF. Look for a wide spot as it curves below the tongue—this is the location of the submandibular ganglion (a parasympathetic ganglion). Cell bodies of post-ganglionic parasympathetic fibers that innervate the submandibular and sublingual glands are located here. Consult Figure 30.16.

■Trace the hypoglossal nerve forward from the neck to below the tongue.

Remember it can be found just inferior to the posterior belly of the digastric and styloyhyoid muscles.

■Identify the inferior alveolar nerve and trace it distally (it has likely been cut, so only a stump may remain). Just before it enters the mandibular foramen it gives off a thin motor branch to the neck called the nerve to mylohyoid and anterior belly of digastric, which runs inferiorly on the medial side of the mandible. See Figure 30.16.

Its function? What else—it innervates the two muscles in its name!

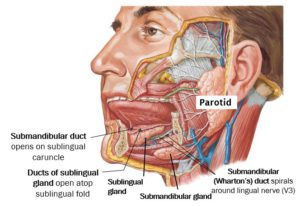

■Clean the submandibular gland and the facial artery twisting around it. Note that the submandibular gland has a large superficial part (external to mylohyoid in the submandibular triangle) & a small deep part (above the mylohyoid muscle in the floor of the mouth). The 2 parts of the gland connect by curling around the posterior “free edge” of the mylohyoid, like the letter “U”. See Figure 30.17.

■Clean the sublingual gland, located just behind the chin (Figure 30.17). It is a small thin gland. At first, you may not recognize it since it may not appear very glandular and can be pale in appearance.

■Starting at the deep part of the submandibular gland and using the lingual nerve as a landmark, search for the flat, thin, white duct of the submandibular gland (Wharton’s duct). It can be tricky to find. See Figures 30.17 and 30.18.

■The lingual nerve and submandibular duct twist around one another.

■The lingual nerve and submandibular duct pass medial to the sublingual gland, between the gland and the genioglossus muscle.

■Review: Where does the submandibular duct open in the oral cavity?

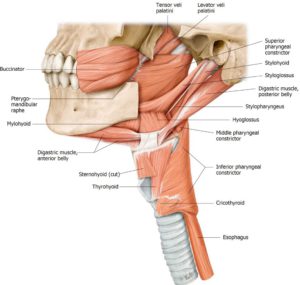

Cut the mylohyoid muscle down the midline and reflect it inferiorly and out of the submandibular triangle.

Now you can locate the hyoglossus muscle. It ascends from the hyoid bone to the root of the tongue. This muscle is a landmark.

■The lingual nerve, submandibular duct, and hypoglossal nerve are on the EXTERNAL surface of the hyoglossus.

■The lingual artery and glossopharyngeal nerve pass INTERNAL to the hyoglossus.

■Figure 30.19 summarizes these points.

Stylo-muscles

With a finger, palpate the styloid process by probing deeply, posterior to the infratemporal fossa and anterior to the ear.

Starting at the styloid process, clean and trace the stylohyoid, styloglossus, and stylopharyngeus muscles. They can be identified by their orientations and destinations. See Figure 30.20.

■The stylohyoid is intimately associated with the posterior belly of the digastric.

■The styloglossus blends with the hyoglossus in the root of the tongue.

■The stylopharyngeus is the deepest since it descends to the pharynx.

■The glossopharyngeal nerve is located on the posterior border of the stylopharyngeus (the only muscle that CN IX supplies!). It is not very large and a bit difficult to identify.

Each of the “Stylo” muscles has a different innervation. Can you name them? This also means they have different embryonic origins.

Pterygopalatine Fossa (PPF)

Grab a skull and pipe cleaners.

The pterygopalatine fossa is a small cavity, no bigger than your thumbnail, deep in the skull. It is a major crossroad for nerves and vessels supplying the oral cavity, nasal cavity, and orbit—but difficult to access clinically.

In lab, you are responsible for identifying the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF) on a skull and identifying the major bony passageways/foramina that connect the pterygopalatine fossa to other regions in the head. In the Large Group session we will discuss the contents of the PPF. However, we won’t be dissecting the fossa or identifying its contents in lab.

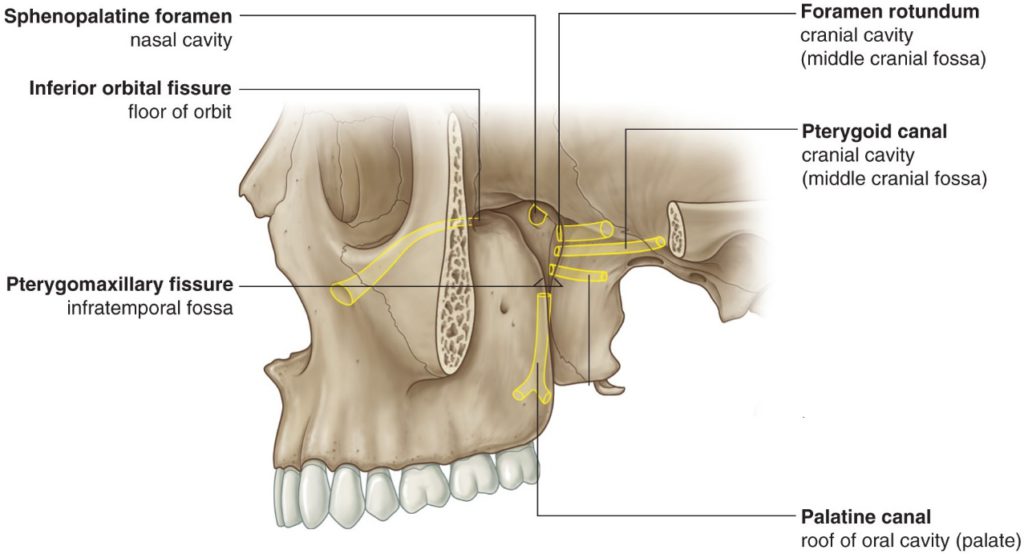

Identify the pterygomaxillary fissure in the skull. Recall that this fissure is in the medial wall of the infratemporal fossa. Place a pipe cleaner through the pterygomaxillary fissure—the tip of the pipe cleaner is in the pterygopalatine fossa. See Figure 30.21.

Borders of pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 30.22):

■The maxilla is the anterior wall (purple in Figure 30.22).

■The pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone is the posterior wall (yellow in Figure 30.22). The greater wing of the sphenoid is in the roof.

■The palatine bone is the medial wall (orange in Figure 30.22). The nasal cavity is on the other side of the palatine bone.

■The lateral wall of the PP fossa is open to the infratemporal fossa—via the pterygomaxillary fissure.

We won’t identity these in lab, but you should know the contents of the pterygopalatine fossa:

■Pterygopalatine ganglion (a parasympathetic ganglion)—the postganglionic neurons whose cells bodies are in the ganglion innervate the lacrimal gland and mucous glands in the nasal cavities.

■Maxillary nerve (V2)

■Terminal part of the maxillary artery: the two most important branches of the maxillary artery in the pterygopalatine fossa are the descending palatine artery (to the palate) and the sphenopalatine artery (to the nasal cavity).

Now let’s identify some foramina that transmit nerves and vessels in and out of the PPF:

■Place a pipe cleaner from lateral to medial through the pterygomaxillary fissure—through the PPF—and into the nasal cavity. Verify this by looking in the nasal cavity through the piriform aperture. The pipe cleaner has passed from PPF to nasal cavity through the sphenopalatine foramen. The sphenopalatine artery follows this route as do branches of V2 that innervate the nasal mucosa.

■In the middle cranial fossa, place a pipe cleaner through the foramen rotundum. The tip is now in the PPF. Verify this by looking in the PPF through the pterygomaxillary fissure. The maxillary nerve (V2) enters the PPF via this route.

■In the orbit, pass a pipe cleaner backwards through the inferior orbital fissure. The tip is in the PPF. Verify this by looking in the PPF through the pterygomaxillary fissure. The infra-orbital and zygomatic nerves (branches of V2) and the infra-orbital artery (from the maxillary artery) use this route to get from PPF to orbit.

■Examine the inferior surface of the hard palate. Find the greater palatine foramen. You might be able to pass a small pipe cleaner up through the greater palatine foramen and then the palatine canal into the PPF. The palatine nerves (greater and lesser) and the descending palatine artery (from the maxillary) take this route to get from the PPF to the palate.

■Locate the foramen lacerum in the floor of the cranial cavity. Imagine a small passageway connecting the anterior wall of the foramen lacerum to the PPF. This is the pterygoid canal (Vidian canal). The greater petrosal nerve (a branch of CN VII) uses this route to reach the PPF, carrying preganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers to the pterygopalatine ganglion, where they will synapse. Postganglionic axons emanating from the ganglion innervate the lacrimal gland as well as mucous glands in the nasal cavity.

A summary of these passageways is shown in Figure 30.24.

Checklist, Lab #30

Review your dissection and make sure you have identified each of the structures in the checklists that follow.

Bony Anatomy of Temporal and Infratemporal Fossae and Mandible—see the first section of this dissection guide.

Muscles

Masseter

Temporalis

Medial and lateral pterygoid

Mylohyoid

Digastric—anterior and posterior bellies

Geniohyoid

Stylohyoid

Styloglossus

Stylopharyngeus

Hyoglossus

Nerves

Buccal nerve of V3

Deep temporal nerves

Lingual nerve

Submandibular ganglion

Inferior alveolar nerve

Nerve to mylohyoid and anterior belly of digastric

Auriculotemporal nerve

Hypoglossal nerve

Glossopharyngeal (Wish list You are an anatomy god if you can find it)

Chorda tympani (Wish list A good find and definitely pin test worthy!)

Vessels

Superficial temporal artery

Maxillary artery

Middle meningeal artery

Inferior alveolar artery

Deep temporal arteries

TMJ

Articular disc (meniscus) of TMJ

Other

Submandibular gland

Duct of Submandibular gland (Wharton’s duct)

Sublingual gland

Pterygopalatine fossa

Bony canals that connect to the pterygopalatine fossa:

Pterygomaxillary fissure

Foramen rotundum

Inferior orbital fissure

Greater palatine foramen

The Pterygoid canal (Vidian canal) connects the Foramen lacerum to the Pterygopalatine fossa (see an isolated sphenoid bone)