- Self-study learning goals

- Define and identify the following:

- The normal QRS direction.

- Describe the pathophysiology of LVH.

- Describe examples of pressure overload on the left ventricle.

- Describe examples of volume overload on the left ventricle.

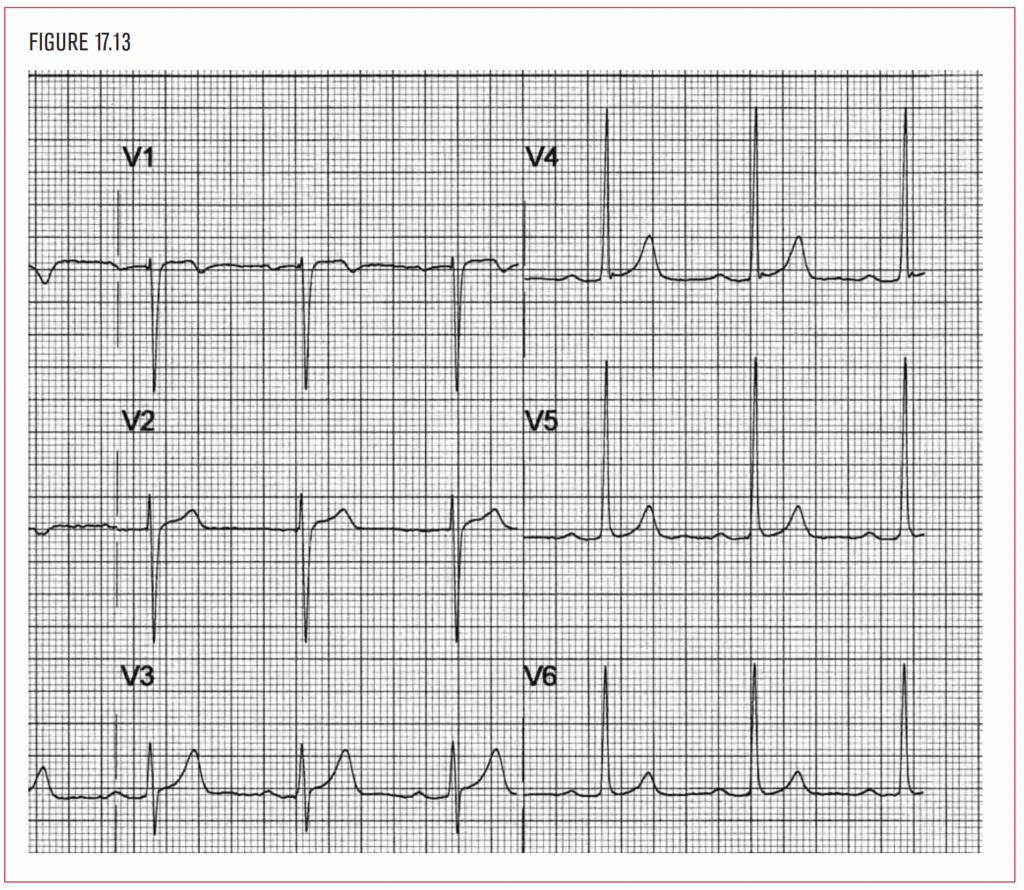

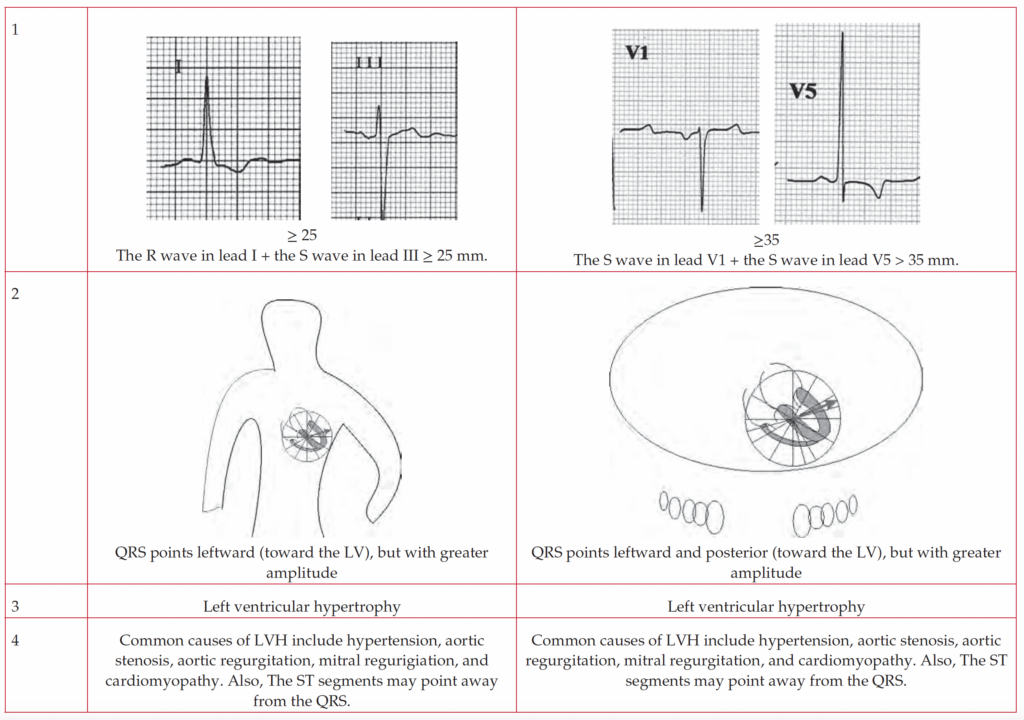

- List criteria for the diagnosis of LVH on the EKG.

- Identify LVH on the EKG.

- Describe and identify ST changes in LVH.

- Identify LVH simulating anterior wall infarction on the EKG.

Overview

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) refers to an increase in the wall thickness or dilation of the left ventricle. LVH is often the result of increased pressure, or volume, within the left ventricular chamber.

- Anatomy

- Pathophysiology

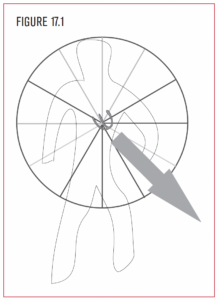

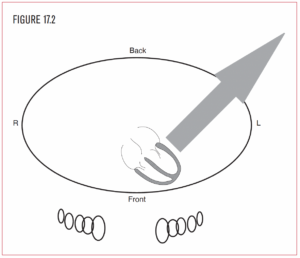

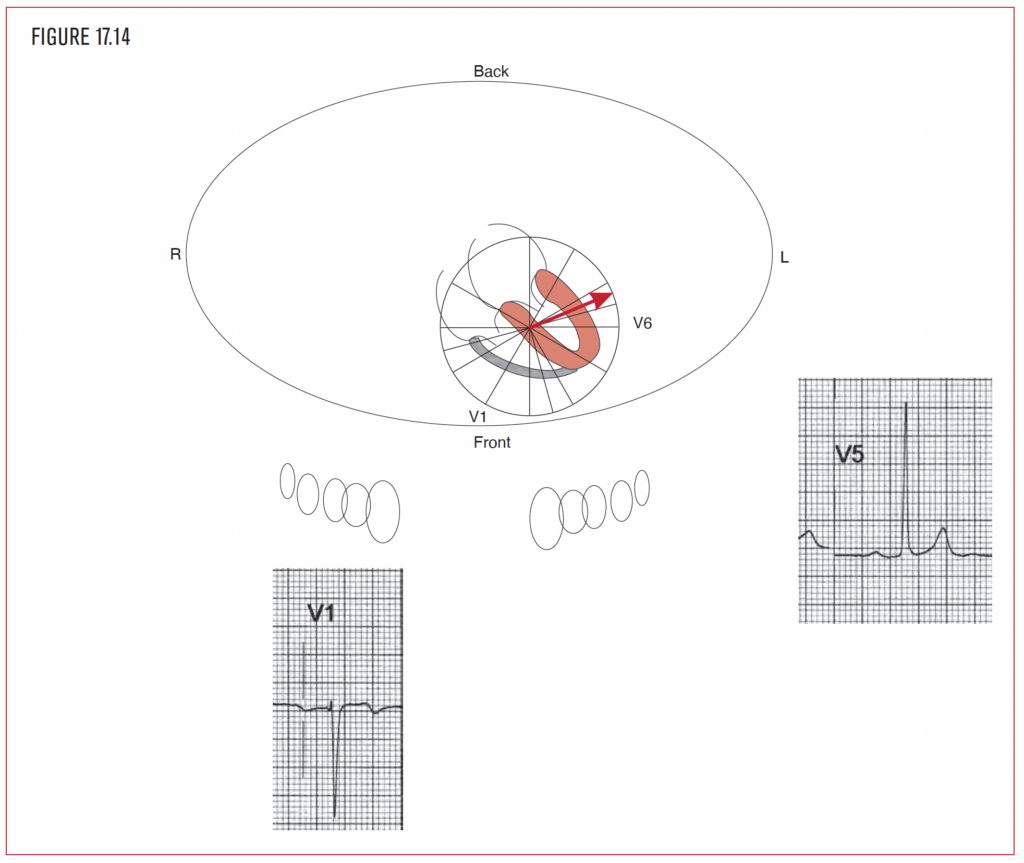

The left ventricle is located to the left and in back of the right ventricle. It is the systemic chamber of the heart and therefore is much larger in size than the right ventricle. Because the left ventricle is larger than the right ventricle, the overall QRS direction normally points posterior and leftward toward the left ventricle (Figure 17.2).

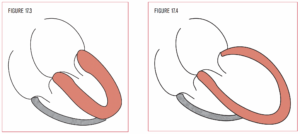

LVH is often the result of an increase in pressure or volume within the left ventricle. When the pressure in the left ventricle increases, it adapts by developing a concentrically thicker wall (Figure 17.3). However, as the ventricular wall thickness increases, the actual cavity size becomes smaller. Increased pressure in the left ventricle is seen in systemic hypertension (HTN), aortic stenosis (AS), and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM or IHSS).

When the left ventricle is strained from volume overload, it compensates by making extra space or dilating (Figure 17.4). Volume overload is often seen in mitral or aortic regurgitation. LVH on the EKG indicates increased LV mass only. It does not distinguish between pressure overload and volume overload.

Volume overload: Mitral and aortic regurgitation

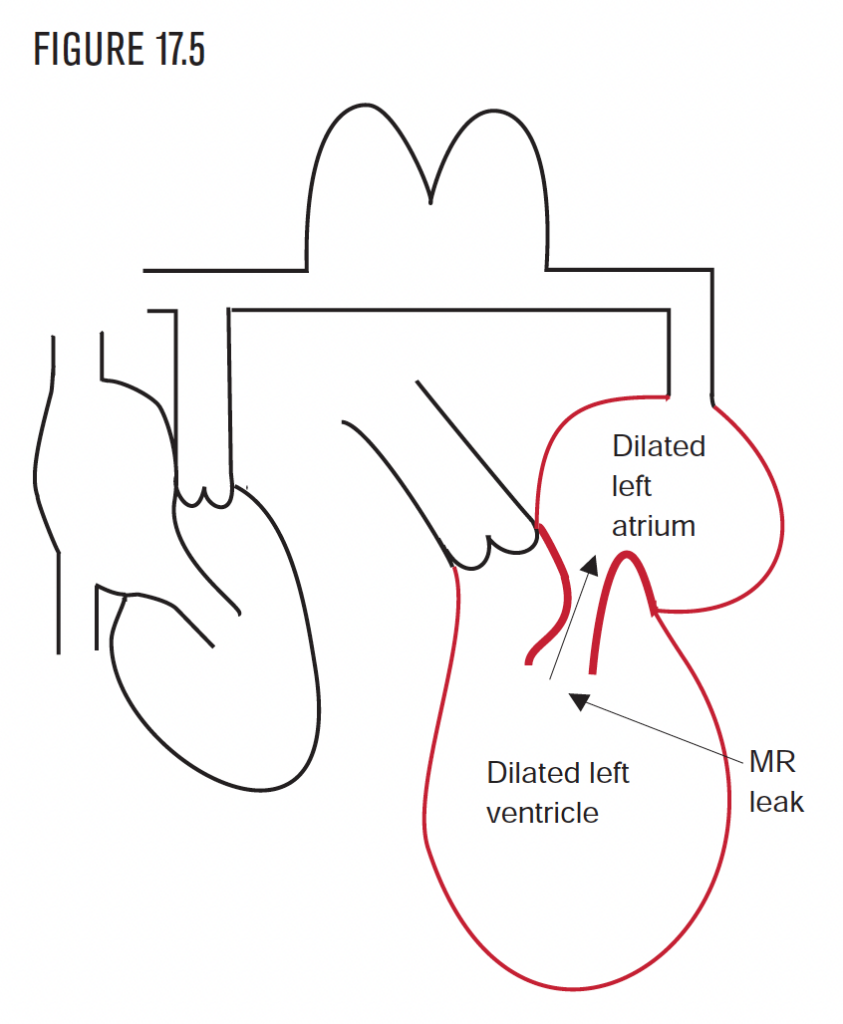

Mitral regurgitation (MR) (see Chapter 16) occurs when the mitral valve allows the backflow of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium. The left atrium and left ventricle become dilated and hypertrophied trying to accommodate the extra blood volume (Figure 17.5).

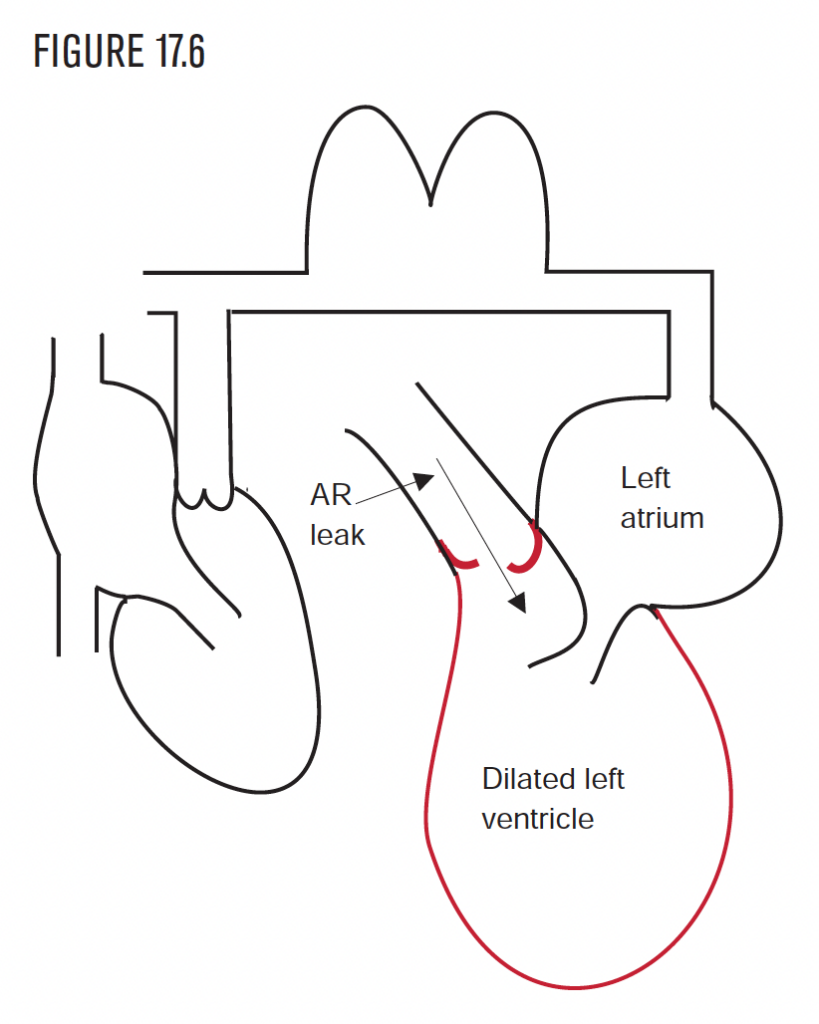

Aortic regurgitation (AR) (Figure 17.6) causes a similar problem. The aortic valve lies between the left ventricle and the aorta. If the aortic valve does not close properly, blood leaks back into the left ventricle from the aorta. Because the left ventricle is receiving blood from both the left atrium and aorta, it stretches and eventually becomes enlarged. This results in LVH. The most common causes of aortic regurgitation are HTN and rheumatic heart disease.

Pressure overload: Hypertension and outflow obstruction

The most common cause of pressure overload is hypertension (HTN). The presence of LVH on the EKG in the setting of HTN establishes the presence of hypertensive heart disease and should prompt an investigation for other manifestations of end organ damage because of HTN.

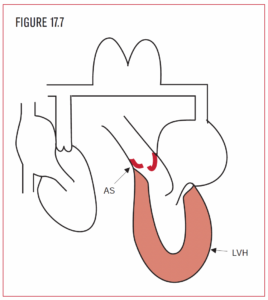

Aortic stenosis (AS) (Figure 17.7) is a less common cause of pressure overload, but should be suspected with LVH on the EKG in the absence of HTN. It develops when the opening of the aortic valve becomes narrowed, restricting the flow of blood out of the left ventricle. The left ventricle hypertrophies to provide the extra force to push the blood through the aortic valve. The most common causes of AS are rheumatic heart disease, congenital malformation, or calcification of the bicuspid or tricuspid valve.

Aortic stenosis (AS) (Figure 17.7) is a less common cause of pressure overload, but should be suspected with LVH on the EKG in the absence of HTN. It develops when the opening of the aortic valve becomes narrowed, restricting the flow of blood out of the left ventricle. The left ventricle hypertrophies to provide the extra force to push the blood through the aortic valve. The most common causes of AS are rheumatic heart disease, congenital malformation, or calcification of the bicuspid or tricuspid valve.

In pressure overload of the left ventricle from any cause, the left atrium hypertrophies as well. The left atrium “bulks up” to develop enough force to push blood into a thick, muscular, unrelaxed ventricle. HOCM or IHSS is a less common cause of LVH.

EKG approach in LVH

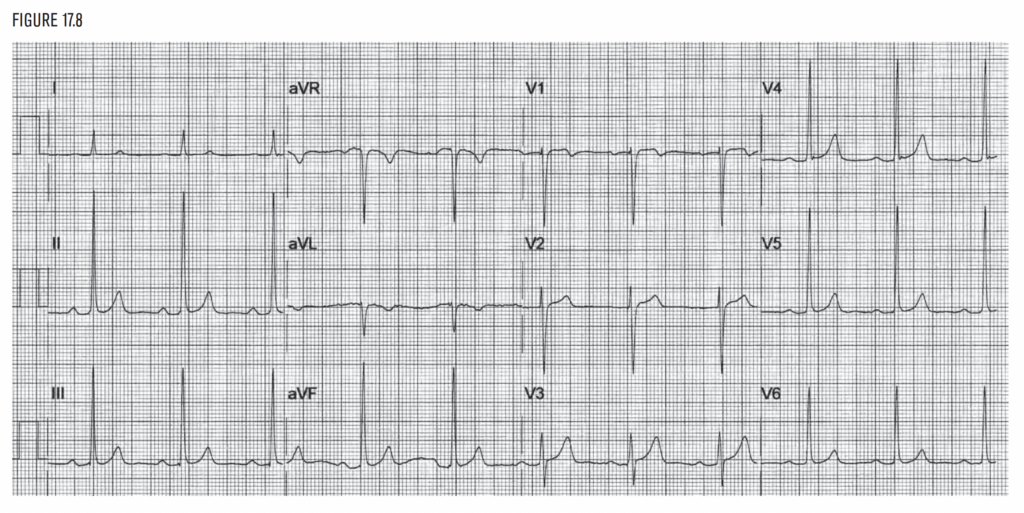

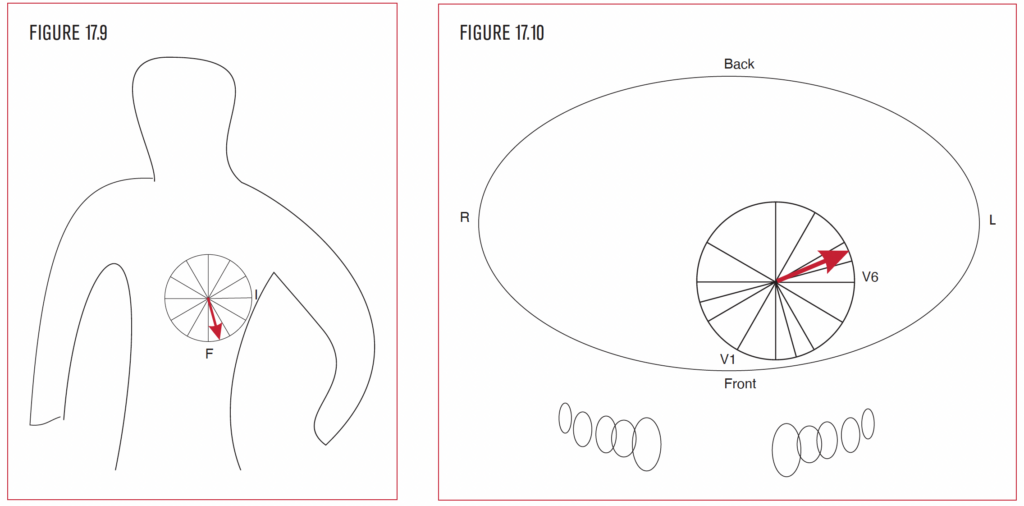

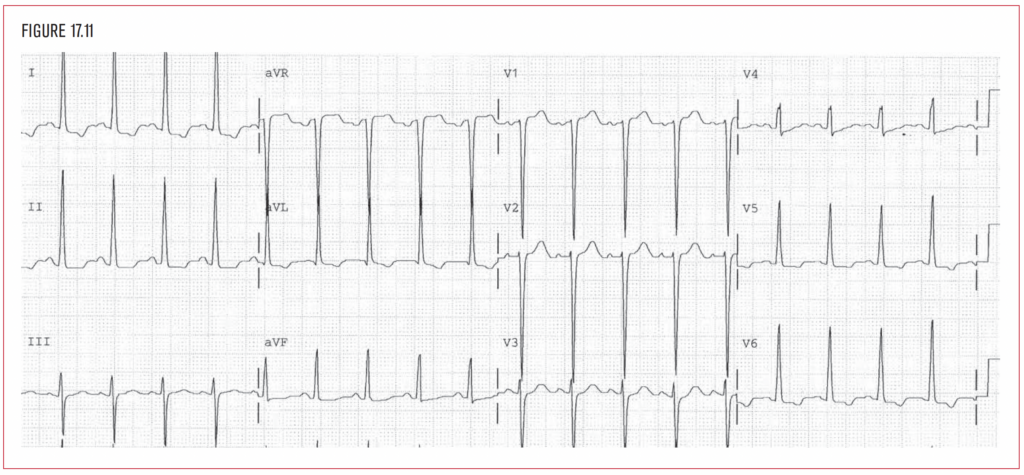

Hypertrophy (Figure 17.8) of the left ventricle increases the amplitude of the left ventricular forces, because more mass generates more electricity. However the overall direction of the QRS is not really affected, as the left ventricular forces already predominate over the force generated simultaneously by the right ventricle. In the example of LVH in Figures 17.8 to 17.10, the mean QRS direction in the frontal and horizontal planes lies within the normal range, that is, to the patient’s left and posterior. This is one of the cases where visualization of the direction of the force really does not help. The increased mass of the left ventricle (whether concentric with a small cavity or eccentric with a dilated cavity) increases the size (amplitude) of the QRS force. In LVH, the frontal plane, the horizontal plane, or both may show increased QRS amplitude. There are separate criteria for each plane.